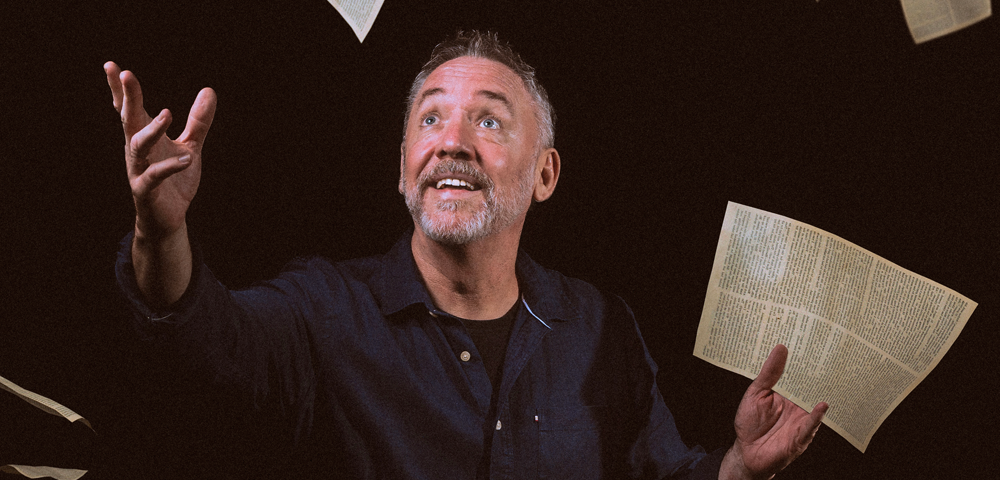

Behind The Aunt’s Story

Patrick White -“ Australia’s only winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature so far -“ was a sensitive, complicated woman, perhaps several of them, trapped in the big-boned body of a bad-tempered bloke.

It’s funny how times change. White’s name is rarely mentioned nowadays. Yet 20 years ago he was Sydney’s most controversial and significant artistic character. Nicknamed Ethelred the Unread by those who found his books too hard, and the Last of the Great Russian Novelists by others for the dramatic sweep and moral power of his lengthy works, his novels, including The Tree Of Man, Riders In The Chariot, Voss, The Vivisector, and A Fringe Of Leaves, were considered internationally as some of the finest 20th-century English fiction.

Having lived reclusively for many years on a small farm at Castle Hill, he and his partner Manoly Lascaris moved to a house in Martin Road, Centennial Park, in 1964. There he also remained largely out of view until some plays he had written decades earlier were produced to considerable success, inspiring him to write four more. That run of opening nights brought White out into the public gaze part of the way.

After winning the Nobel Prize in 1973, he was also asked to contribute the weight of his status to back many public causes. He was a great supporter of Gough Whitlam and Jack Mundey’s Green Bans; he was against uranium, logging, and anything to do with Her Majesty The Queen. These often very public stances forced him reluctantly even further into the spotlight.

The first time I ever saw him in the flesh was on a podium outside the Sydney Town Hall. There were thousands of us hanging off his every word, though I can’t remember the precise cause that day.

While he detested the Gay Mardi Gras nonsense, particularly since so many non-gay trendies seem to have jumped on the wagon (from a letter to Jim Jenkins, 1984), he was never closeted. Private, anti-social, but for the era, uncharacteristically out.

Many who never knew him gossiped about his appalling misogyny. The truth is almost all his best characters and many of his closest friends were women. It could be a frightening prospect, letting White get to know you. Over the years Patrick made, sometimes actively pursued, acquaintance with a range of women who found themselves turning up as characters, or bits of characters, in his books.

Such dissection in words for all the world to see was mortifying enough. More shocking, indeed shattering, was the dispute engineered by White that would almost inevitably ensue. Women who had walked across hot coals for him found themselves brutally cast out. It wasn’t misogyny, more like guilt. Or part of the writer’s process: having devoured them artistically, he would hurl their carcasses out onto the lawn. Manoly would beg him to phone back immediately and apologise. More often than not, White would not.

White best loved an actress. As a young man in London he would hover at stage doors to catch a glimpse. In his later years, when he finally relaxed a little, it was the actresses best suited to take on the characters in his plays -“ Kerry Walker, Robyn Nevin and Kate Fitzpatrick -“ that he adored most. He would lavish them with gifts on opening nights and there wouldn’t be a dinner at home or out at one of Sydney’s latest restaurants without one or more of them gracing the table.

The roles he was unable to play on stage (he loved Cleopatra best), he acted out in the pages of his books -“ from the dowdy spinster, Theodora Goodman (with her moustache), in his 1948 novel The Aunt’s Story, to Eadie Twyborn, in the 1979 novel The Twyborn Affair, whose veiny hands at the piano are the first giveaway that this glamorous sophisticate is not all that she leads others to believe. All the other books, apart from The Solid Mandala (which most closely resembles life with Manoly), are dominated by women. Even Voss, his most acclaimed work, is as much a study of Laura Trevelyan as it is of her lover, the explorer White called Voss.

Women he not only liked, indeed preferred, but also seemingly understood. Some might say too well.

I was a guest at a surprise birthday party for White some time in the late 1970s, a surprise that at first did not go down well. Later the host revealed the reason for the aghast expression on White’s face as he stood at the door. Apparently he had been expecting only the host and his boyfriend and had put some considerable thought into arriving in drag. There before him swayed some of Sydney’s most salubrious personalities.

It was certainly the women of his early childhood, including his daunting mother Ruth, who shaped White’s temperament. Growing on a farm, there were men around too. Mostly hard, rough men. The men White lived with when working as a jackeroo in the Monaro after returning from school in England were similarly hard men, as were the blokes he worked with as a member of British Army Intelligence in North Africa through World War II.

Meanwhile, the softness, the femininity if you like, that lay at the core of Patrick White was pressed into a trembling tiny hot core. He would dig for this, under great emotional pain, when he eventually sat down in adulthood to write his books.

It was during the war that White met Manoly Lascaris in Alexandria. White died, aged 78, in September 1990. Lascaris, who turned 90 just a couple of weeks back, though frail, still lives in the Centennial Park house.

We haven’t met up for some years, but in an interview he offered me not long after White died, Lascaris remembered vividly his first encounter with Patrick White.

I had a friend who was a very wealthy Jew, said Manoly, who used to entertain people in the forces. He asked me to a party he was giving because he had an Australian staying. There was no Australian when I arrived. Just all sorts of Alexandrian young men. I knew them all, but none of them were the kind you would waste your time on. Very swish creatures.

Anyway the baron had a series of salons in which he would receive friends. If the butler said, -˜Come into the Louis Quinze salon,’ that meant all the right people, ladies, bankers. He had a Japanese salon for those who were not of the -˜right society’, but because of his inclinations they were his friends. All of a sudden Patrick appeared through the sliding doors, and all the guests rushed up to him.

Except Manoly, who didn’t move. I stayed at the very end of the room.

After a bit, the Baron said: -˜Shall we go into the Salon Japonaise?’ I stayed behind and Patrick stayed behind. They introduced themselves and began a conversation. On the way to the Japanese salon, explained Manoly, there was a rather beautiful painting on the wall of a cardinal, in the Velasquez style. I stopped to look at the painting. Because it had that very piercing look I noticed in Patrick’s eye. It was the first thing I noticed when he came in -“ that’s why I held back. Then all of a sudden, when I was looking at the painting, Patrick put his arm around me. He asked if Manoly would like to see his bedroom.

Any reader of Sydney Star Observer would have already noted that this was pretty much a typical gay pick-up, right down to variously decorated salons and the old -˜looking-at-the-painting-on-the-wall’ trick.

But here Manoly’s narrative lifts it to another level. This was to be no brief encounter. Nor was it a romance, Manoly said. It was an attraction through the eyes. I thought to myself when I saw that look: Well, I may have a terrible life, but I must go through with it. Why? I thought I couldn’t escape it. I think Patrick thought the same.

Write was already a writer with a couple of works published. But he was undisciplined. It was Manoly who insisted he get out of bed and dressed before the maid arrived. In fact it was on Manoly’s Alexandria balcony after the war that White wrote a large part of The Aunt’s Story. It is one of White’s best novels, and the title character, Theodora (Theo) Goodman, one of his finest female creations. Starting off as a dowdy Australian spinster, she leaves for Europe after her mother dies, just as war breaks out, to try to find her true self. In part three, she finally goes completely mad as she travels across America.

Manoly was never one of the women, one of the soft ones, in Patrick’s life. However difficult the relationship was at times, Manoly was the rock. He might have been stubborn at times, but that is what a rock is meant to be. He was horrified when the article about him I had published, which won me an award somewhere, was called The Widow White. How do you know I’m not Widower? he smiled cryptically.

Â

Director Adam Cook’s own stage adaptation of The Aunt’s Story opened at the Belvoir Street Theatre on 14 August with Helen Morse in the title role.