Can I adopt or foster a child?

Choosing to provide a home to one of the many children who need one can be incredibly rewarding. But same-sex couples are not yet treated equally in NSW. A combination of discriminatory laws and the attitudes of service providers and relinquishing parents make it harder -“ but not impossible -“ to apply to adopt a child. However, these difficulties may make long-term foster care placement, particularly of older children, a more realistic alternative than adoption for many lesbians and gay men wishing to parent.

The NSW Department of Community Services (DOCS) provides adoption placements, as do a small number of non-government agencies. DOCS is a good first port of call for information (see its website). Adoption involves a process of applying, being assessed and, if found to be suitable, being placed on a waiting list until a matched child becomes available. This process can take some time.

General eligibility criteria for adoptive parents include: psychological, emotional and financial stability, a clear criminal record and good reputation, Australian citizenship, and a willingness to assist the child to have contact with the birth family in the future. If you are in a relationship it must be at least three years in length. If there are any other children being cared for in your family they should usually be two or more years older than the child to be adopted. You or your partner cannot be pregnant or in a fertility program.

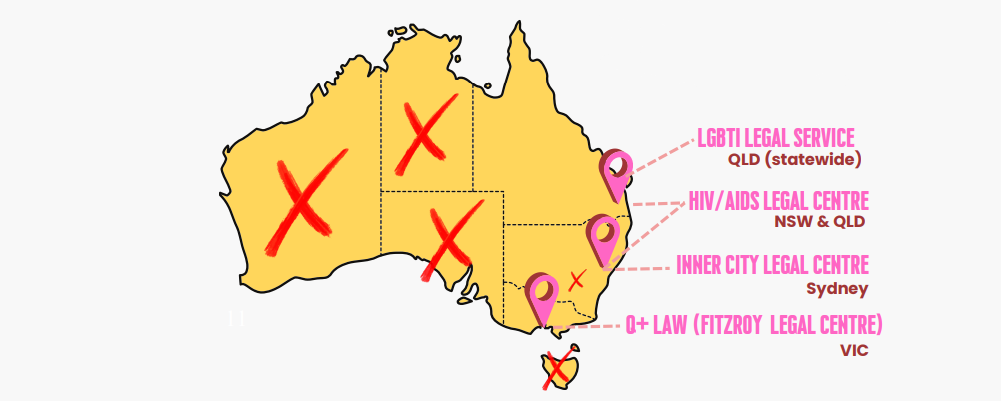

Although Western Australia and the ACT now permit same-sex de facto couples to apply to adopt a child, NSW does not (the DOCS website misleadingly says de facto couples are eligible without specifying that it means only heterosexual couples). Lesbians and gay men cannot apply as couples in NSW, but are still able to apply as individual applicants. This means that both partners are still assessed for suitability but only one partner will be the legal parent if a child is placed with you. Since 2000 there is no formal preference for couples over individual applicants in NSW law (again the DOCS website is wrong on this), but relinquishing parent preferences and overseas law may still mean a lower priority in the waiting list.

There are very few children available for local adoption. In the under 2 age range, DOCS states that only around 15-25 children are adopted through it each year in NSW. Parents giving up their child are involved in the placement process and their wishes usually determine that the baby goes to a heterosexual couple rather than an individual applicant.

While birth parents are not involved in the adoptions of older children, there are also relatively few children available to be adopted as they are generally placed in foster care if their home environment is no longer suitable.

Intercountry adoptions are now far more common than domestic adoptions in Australia, making up around three-quarters of adoptions in recent years. Such adoptions must satisfy the requirements of the Hague Adoption Convention, which requires eligibility for adoptive parents to be agreed upon by both the child’s country of origin and the country in which they are adopted. At the moment none of the current sending countries allow same-sex couples to adopt (although note that when South Africa begins intercountry adoptions, as it is expected to do in the near future, it does recognise same-sex couples as eligible to adopt).

Some sending countries such as China, Taiwan, the Philippines and Hong Kong allow an individual applicant to adopt. (Ethiopia will only accept female individual applicants.) The DOCS website notes that the current waiting time for a couple accepted to adopt a child from China is seven and a half months, but for individual applicants it is three years. Just because Angelina Jolie can jet in and out in a week doesn’t mean that anyone else can. The process of assessment is complex, and adoptions must be undertaken in Australia and approved by DOCS for the child to be permitted to enter Australia.

The current cost from DOCS is $10,700 for assessment and placement of a child for intercountry adoption. Other expenses such as legal advice, visas and so on mean that the total cost can be much higher.

In 2004 the Howard government tried to ban any state agency from providing intercountry adoption to a same-sex couple. This was part of the first bill to ban same-sex marriage. The adoption ban was dropped from the law after opposition parties said they would block it in the Senate. However, it is entirely possible that it will be reintroduced now that the government controls the Senate, and some backbenchers have already called for this to happen. If passed it would mean that lesbians and gay men in Australia could not adopt a child from overseas even as individual applicants.

There is a much greater need for foster carers than for adoptive parents in Australia. DOCS states that carers can be an individual, couple or family, any age or gender and can be living in a range of different situations. The need for carers to take older children and sibling groups is particularly acute. DOCS states that it also particularly needs foster parents who are Aboriginal and from various cultural backgrounds, as it tries to match children with carers who are culturally appropriate.

In addition to DOCS, several non-government agencies provide foster care placements. Be warned that virtually all of the non-government providers are religious. Some, such as Barnardos, have a history of treating same-sex couples equally and with respect. Others, such as Wesley Mission, have been openly hostile to lesbians and gay men.

Many agencies specialise in different kinds of placements, for instance in children aged 2-12, or adolescents, or children with disabilities. DOCS has a list of providers on their website with links you can access to find out some more information about them.

The stated aim of foster care is to return children eventually to their families of origin. One of the required qualities in a foster carer is the ability to say goodbye when the time comes for families to be reunited. Nonetheless there are many long-term foster care placements. Sometimes children are eventually adopted by the foster parent.

To become a foster parent, you must go through an assessment and then, if found to be eligible, a training process. Different agencies list various eligibility criteria such as: a clear criminal record, previous experience in child rearing, a stable and secure environment, stable relationship status, and the ability to provide the child their own room. If a child is placed, foster parents are provided with on-going training and support as well as economic assistance.

Jenni Millbank is associate professor of Law at the University of Sydney and special advisor to Watts McCray Family Lawyers.

If you need legal advice you can call Watts McCray on 9635 4266 and speak to Lorraine to make an appointment.