Cutting the cloth

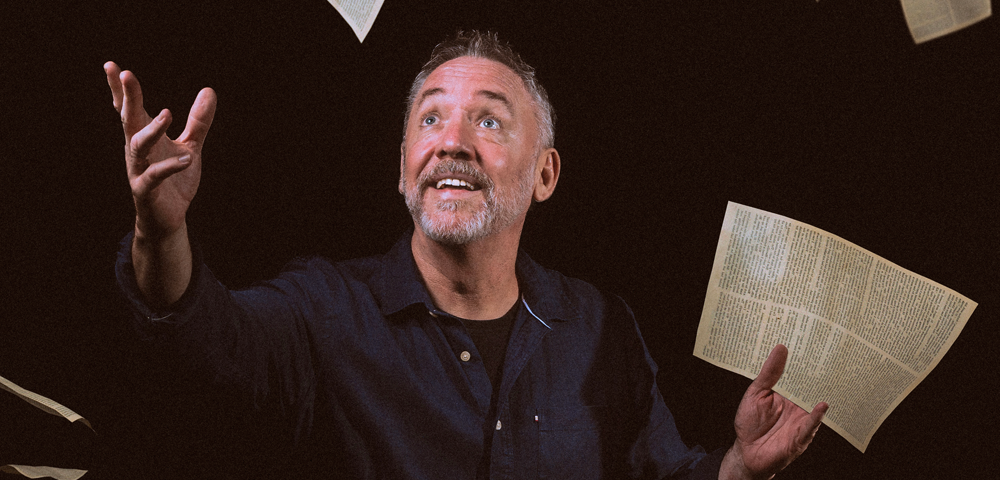

Dorothy McRae-McMahon will be remembered by many as the Uniting Church’s national director of mission, the Church’s second highest office bearer, who became embroiled in controversy when she came out as lesbian in 1997. Although there were many in the Church who supported her, both for her obvious talents and for her courage, eventually she resigned, perhaps more as a sign of the Church’s inability to deal with the issue rather than as a result of the political recriminations.

She still talks of that time as very wounding but she is not one to wallow in any kind of self-pity for too long. She quickly goes on to talk of her determination to stay connected to the Church, partly out of stubbornness and partly out of integrity.

I also stayed there -¦ because I am still part of the Church whether some people like it or not.

Her new book arises out of both practical experience and a love of writing.

Despite appearances and my endless capacity to talk, my best way of recovery is by myself and through writing. I just love writing, I probably write three or four hours a day, she tells me.

But unlike her other books of autobiography and reflection, for her new book of rituals and meditations she found she needed to find a new language that was somewhere between poetry and prose -“ a language of understatement that matched the rawness of real life.

When I did retire and I was perceived as a kind of very naughty Christian on the edges of the Church, I was really surprised at how many people began to ask me to create something for them to mark some kind of life passage, McRae-McMahon says.

So when I was asked to speak at something or launch something, I’d find myself -“ just because of who I am, because I’m a priest, if you like -“ I’d end by saying something like: -˜I just want to put this beautiful purple cloth there to image the passionate life that is in this moment,’ and I’d just place a flower there, something as simple as that, and people would have tears in their eyes.

This became a kind of trademark of McRae-McMahon’s style and she found people would ask her to do something just a little bit spiritual when inviting her to talk at or launch an event.

The resulting book is practical and straightforward. It includes rituals for all manner of occasions, such as marriage, milestone birthdays, the miscarriage of a child, the death of a pet and blessing a home. Other rituals are more introspective such as those focused on forgiving yourself.

In her introduction McRae-McMahon writes of the comforting structure provided by rituals.

We are given boundaries for entry into our grief and pain and a special solemn joy in celebration. People who feel that they may never stop if they begin to cry are often given a sense of security by the formality of a ritual and the fact that someone else is in charge and will take them through certain processes with clarity and responsibility.

McRae-McMahon knows that while the structure and language must be strong, it must avoid the triumphalism of traditional liturgical language.

Ultimately, of course, ritual is an action, not a form of words.

If you use what are archetypal symbols like water and earth and wood and cloth -“ especially cloths, you can do a huge amount with cloths, long swirling cloths -“ then whoever they are, people understand what you are doing, and they feel that the moment is more significant. You can say all the words you like about launching something, but if you mark it like that, people think: -˜That was important,’ she says.

McRae-McMahon says that she wrote this book out of a deep love of this city and its people.

I deeply, deeply love, this country, particularly Sydney, and I just love its people. I am so sorry at the wounding, what the church has done in its judgment on the people of this society. I am angered that they are thought of as secular when they have their own deep and very fragile and very self-conscious spirit.

Part of that spirit is a type of resilience, our famous no-bullshit attitude, but McRae-McMahon also detects something else.

There’s something painful and raw running underneath this society. I think there is a very deep grieving on many, many levels running under all of our culture here. We don’t talk about it but it’s there: the pathos. Leunig is right, there’s that pathos in his little person.

I think it probably starts with the treatment of indigenous people and that’s always raw underneath, possibly forever. But also if you think that this society was built on layers and layers of people, first of all those who were pushed out of their own society, others who’ve been refugees, others who have come out here to try to survive for some reason. Of course some have come because they wanted to but we do have layers and layers of people who have experienced loss as well as, hopefully, finding something.

She hopes her book will speak to that spirit of this country, the pain and sense of loss, but also what she calls, at another point in our conversation, the tough reality check, the hard won answers and the humour.

A lot of her insights are hard won. It comes from working in urban, largely poor, parishes where no bullshit could be a liturgical anthem.

I love that raw stuff of relating with people, the sense that you can’t mess with them and you can’t mess with your own view of life either because they’ve got all the hard questions and they’re not going to fall for any of your romantic or slick answers and you can’t fall for them either if you’re going to live with them.

Dorothy McRae-McMahon’s Rituals For Life, Love & Loss is published by Jane Curry Publishing.