Gay Games legacy

With the zeal typical of an American TV evangelist, the title page of the website for the international Federation of Gay Games proclaims, Games can change the world.

It’s not a promise, it’s a statement of possibility. The Sydney 2002 Gay Games sparkle and glisten with the lustre of potential: for individuals, for sponsors, for Sydney’s lesbian and gay community, for the global lesbian and gay community, for Sydney itself, for New South Wales and for the Federation of Gay Games.

But balancing that, much is at stake. Sydney 2002’s reliance on revenue derived from dance party ticket sales leaves the organisation in a far-from-certain financial position, and if the Games are perceived as a flop, the ramifications for all the groups mentioned above could be profound -“ most seriously for gay and lesbian Sydney.

However, some people argue that the Games are already having a positive impact on Sydney’s lesbian and gay community.

Team Sydney representative Paul Long says Sydney’s gay and lesbian sports scene has grown significantly in the past few years.

We know that several new sports clubs came into existence as a result of individuals wishing to form the necessary network and capacity for training to enable them to participate in the Games, he says. Six new teams have come into existence or affiliated with Team Sydney in the past 18 months, while other teams, such as the Sydney OUTfielders softball group, report booming attendances, Long adds.

It is our hope that the lasting legacy of the 2002 Gay Games will be greater participation generally in sport by gays and lesbians. Sport represents a healthy lifestyle choice -¦ it’s a great way to meet people away from the traditional bars and clubs lifestyle, Long says.

That healthy lifestyle alternative is one that is sometimes denied to people in our community -“ particularly to young gay men, argues Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby co-convenor Anthony Schembri.

We know from social research that for young gay men growing up, sport is often an area that we are bullied in or don’t have an equal fair access to, he says. So for those reasons the Gay Games is important from a human rights perspective.

The Gay Games offer us the chance to get involved in something we are not known for -“ and thus smash a few stereotypes. Sydney 2002 sports director Stuart Borrie put it this way when he spoke to the Star back in 1998: There is a perception that gay men can’t catch, and if you’re a lesbian you can only play either softball or soccer.

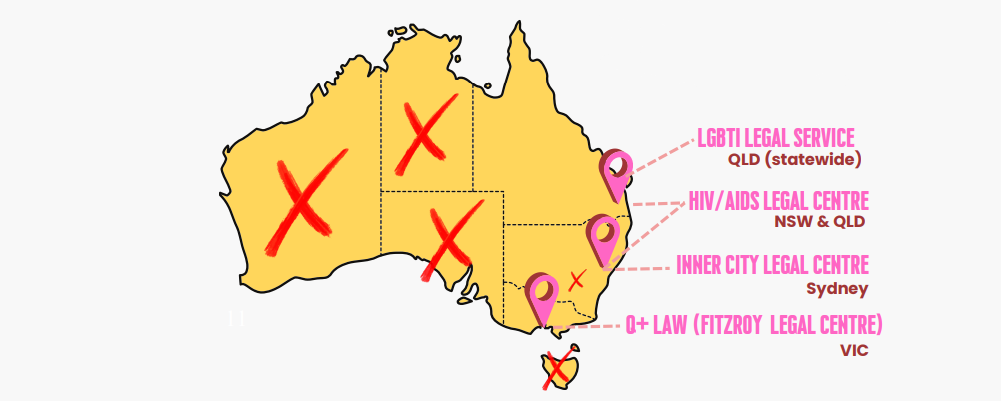

The timing of the Games means we can do more than fashion ourselves a new image, however. Coming just five months before a state election, the Games will provide political activists with an opportunity to point out a rather obvious anomaly: that New South Wales is a state which can host some of the greatest celebrations of gay and lesbian life anywhere in the world, but it lags behind every other state in Australia when it comes to lesbian and gay law reform. Schembri says the Lobby will be running with that message every time they are interviewed by foreign media outlets. The conference program should also provide a platform for the airing of many and varied gay, lesbian and general human rights issues.

However, it is doubtful that the Gay Games will directly spur on any fresh bursts of law reform. Indeed, there are some fears that, should the Games lose money and need to be bailed out, the program for progressive gay and lesbian law reform in this state could be delayed or even derailed. Should the Games need to be saved -“ and organisers are confident that’s not going to eventuate -“ it would be a hard sell to the electorate for any government to support the Games and then immediately afterwards progress reform on, say, the age of consent. It will be one or the other.

But according to community commentator Craig Johnston, the people who are most going to bear the cost of the Games are the people of Sydney’s gay and lesbian community.

Who’s going to bear the cost? Who’s going to have to come to the party, in terms of being the volunteers and bringing in the money to make it work? he asks. It’s not going to be the state government, who are probably giving as much as they can, politically. (As an aside, he adds: -˜And we’ll never be thankful for that.’)

Somebody’s got to come to the party, and it ends up being middle-aged middle-class men who are expected to cough up in party tickets. Those boys have been financing the gay community for years, Johnston says.

But an interesting thing about the Games, Johnston adds, is that it draws a different group of people to the traditional Mardi Gras/dance party crowd: more women are involved, and there is less emphasis on the body beautiful.

The outreach and scholarships program will also help to bring in a more diverse crowd. Scholarships have been awarded to competitors from 52 different countries. For many of them (some of whom come from countries with homophobic governments and cultures) it is easy to see that the Games will indeed be a world-changing experience.

Ultimately, however, it will be up to lesbian and gay Sydney to make sure these Games work. Some 2,000 Australians are registered competitors, but is the community as a whole engaged?

Johnston thinks our somewhat muted enthusiasm for the Gay Games so far is not dissimilar to the blas?approach Sydney had prior to the 2000 Olympics.

People were excited about the bid for the Sydney Olympics. I think the trouble with the Gay Games bid was that it was an elite bid, he says. There was a small group of people interested in it -“ and of course they were doing it at a time when gay and lesbian identity politics were very different, very strong. It was still on the way up, and people weren’t predicting a crash. Here we are five years later, and gay and lesbian identity politics have crashed; they’re not what they were, so I think that’s a special problem. I think there’s a lot of indifference to the Games from Sydney’s point of view. But I think that will change.

Johnston has publicly called for social impact assessments of flagship gay and lesbian celebrations, as both balance and counterpoint to the economic impact assessments which organisations like Mardi Gras have used several times in the past decade. Social impact studies would help us establish the worth of an event like the Gay Games in something other than dollar terms. The social benefits of an event like the Games may be hard to quantify (lessening social isolation, increasing self esteem for lesbian and gay youth, the breaking down of barriers between gay and straight society, etc.), but that does not make them any less real.

Tourism numbers are a much simpler index to work with than, say, the health and well-being of the community. And these Gay Games are likely to have a huge impact on Sydney’s reputation as a global gay city.

The 2006 Gay Games host city, Montr?, has marketed itself quite aggressively in the gay and lesbian market over the past few years. Their goal is simple: they want to be recognised as one of the top five gay cities of the world. Hosting the Games is a strategic step in the realisation of that goal.

Unlike Montr?, Sydney probably already enjoys that top five status. But that position will be put to the test during late October and early November. Will we be able to meet and exceed the expectations (built on the successes of Mardi Gras and the Olympics) of the international tourists? Will we turn on the Aussie charm? Will we fill the dancefloors? Will it be all right on the night? This time, our reputation is on the line.

One hundred days and counting: fingers are still crossed.