In the heartlands

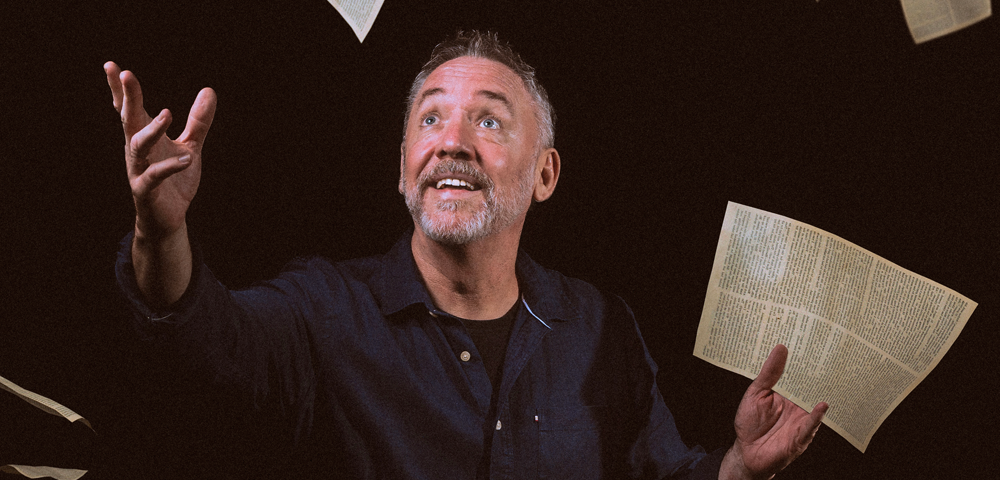

Once upon a time, a certain 200,000-word manuscript entitled At Swim, Two Boys that chronicled the sexual and political awakening of two 16-year-old boys in Ireland in 1915, might never have been published. Once upon a time, (though perhaps later in time) it might have been gently pushed aside as gay fiction, ignored by mainstream critics and consumed by a small but appreciative subcultural audience.

In early 2001 though, Simon and Schuster signed a one-book deal with novelist Jamie O’Neill for £250,000 for this very book, and announced that it was the highest ever advance for an Irish novel. O’Neill, who has a reputation for a level of modesty that renders him almost invisible, murmurs a correction by phone in Ireland.

I don’t know if it was the largest, I don’t know how they picked that up, says O’Neill, but I’m prepared to go along with it. What surprised me was that the book was bought at all.

The shyness may be something of a charming ruse, and certainly to my foreign ears, the combination of gentle self-effacement channelled through an Irish brogue is bewitching. There are perhaps better clues in O’Neill’s past. When he was 27 O’Neill’s partner died from hepatitis and the media hounded him for his story; boyfriend Russell Harty was a BBC talk show host, and O’Neill refused all offers to sell his side of the story to the tabloids.

To add to the devastation, O’Neill was left homeless and penniless when Harty’s family took everything. The following 10 years were spent working as a hospital porter in a mental hospital, tapping up At Swim, Two Boys on a laptop computer. When news of the Simon and Schuster advance hit the UK press in 2001, Gay Times journalist Andrew Copestake wrote that he was worried for O’Neill, and that he seemed ill-prepared. Now that the work has been published internationally, I’m wondering how he has responded to the attention, not to mention the reviews?

I don’t really know what I feel about it. I laugh a lot of the time. When I give a reading I read from The Washington Post review and from The Jerusalem Post review, which are two of the most damning sentences you’ll ever come across in your life. They’re really outstanding.

These reviews prove to be the exception, and a little digging uncovers a phenomenal bounty of positive crits. In the UK, the Independent called it mesmerising, sophisticated and intense and The New York Times, said that this is a gay man’s writing, but it has broken out of all the usual confines while keeping all its emotional particularity. Jamie O’Neill has written a dangerous, glorious book.

Not to mention romantic. In At Swim, Two Boys Doyler teaches Jim to swim at the Forty Foot, a rocky outcrop and nude beach, with the eventual goal to swim out to a nearby island in a year’s time and claim it as their own country. By year’s end (Easter 1916), contact with a young idealist called McMur-rough will awaken and reify their sexual feelings and political beliefs, as the romantic friendship becomes engulfed by the tragic circumstances of the Irish Rebellion.

There have been favourable comparisons to James Joyce, which O’Neill rejects.

There is no such thing as the next Joyce. I’m the next Jamie O’Neill, he says, putting such comments down to the fact that the opening chapters are set at Forty Foot, where Ulysses opens. Nevertheless, O’Neill asserts that its roots are in the Irish literary tradition.

The first chapter is supposed to be Joycean, it’s clear that we’re coming out from this place, O’Neill insists. The last thing I wanted was for my story to be presented as something new out of Ireland. I wanted people to think this has always been here.

There’s a literary continuum here, and a queer one. The lives of historical ante-cedents and contemporaries are a recurring presence in the novel, from Oscar Wilde to Roger Casement. McMurrough’s education of the boys is both sexual and cultural, teaching them about homosexual forbears from the Spartans to Christopher Marlowe. There are echoes of an early gay pride rhetoric, but the boys’ concurrently political and sexual awakening is also echoed in the lives (and fictionalisations) of figures from Colonel Redl to Burgess and Maclean.

When I ask O’Neill whether he personally believes in a connection between sexuality and political awakening or even a certain humanitarianism, he tells me that he wouldn’t have written the book otherwise and that the book answers that question. (O’Neill went so far as to tell the Toronto Xtra that the search for a sexual identity is actually the same as the search for a national identity.)

Not everyone is convinced. The Observer’s Adam Mars-Jones wrote that there may be correspondences between throwing off the yoke of Empire and claiming the right to love your pal in pride and dignity, but no amount of lyrical prose can make them the same thing. O’Neill shrugs it off.

I wanted it to be a book for the young fellas in this country, for their friendship first of all, and their love. That they do discover their own country. There is a passage where Jim says that Doyler is his country, explains O’Neill.

The swim to the island is just a boyhood test of togetherness or courage or endurance to begin with, and then it takes on the metaphor of being Ireland for them -¦ I think Jim at the end, as he grows in confidence and awareness, with his friendship with McMurrough, the only way he can explain it is, -˜you see we’re extraordinary people, doing extraordinary things’. It stops being a metaphor by the end.

Â

Jamie O’Neill will be appearing at the Sydney Writers Festival on Saturday 1 and Sunday 2 June. Phone 9566 4659 or visit www.swf.org.au for more information. At Swim, Two Boys is available from all good bookshops, rrp $29.95. The Bookshop, Darlinghurst is offering At Swim, Two Boys at the special price of $24.95.