The Hours

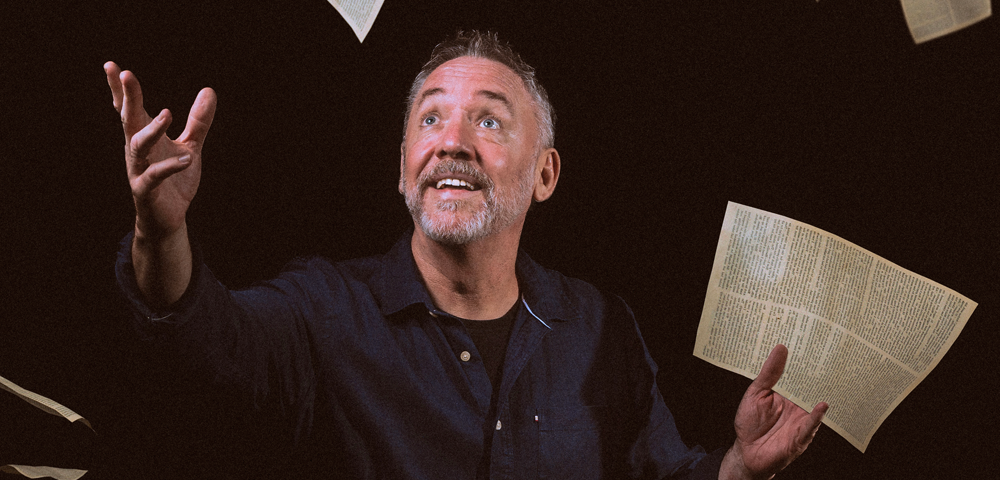

It’s no news that the latest film by the director of Billy Elliot, Stephen Daldry, has gained a number of Oscar nominations. There’s a reason for that. This, only his second film, is an accomplished adaptation of Michael Cunningham’s novel. Some of this is due to the film’s stars, Nicole Kidman, Julianne Moore and Meryl Streep, but also to a strong support cast and some agile editing.

The novel and film, in turn, rely on the Virginia Woolf novel, Mrs Dalloway. And, yes, it helps if you know something about Woolf’s life and work, for instance, that Woolf wrote the novel in 1923, was originally going to call it The Hours and that she didn’t suicide until 1941. It’s useful to know the novel’s main character, Clarissa Dalloway, remembers a passionate kiss with a girl in her youth. And, oh yes, it’s a queer film with more than one in 10 roles being lesbian, gay or bi.

It threatens to be dreary, dealing with suicide, depression, the constraint of women’s needs and the loneliness of the watchful outsider. If there is one thing that could have been asked of the movie was a bit more edge and a little less soulful regret. But that one passionate (though not necessarily sexual) kiss is also an important reverberation in The Hours.

The film’s three stories are interwoven effortlessly and small visual details, such as a vase of flowers, are touchstones that connect each story. In the present, there is Clarissa Vaughn (Streep), a lesbian book editor, nicknamed Mrs Dalloway by her friend and client Richard (Ed Harris), a man dying of AIDS. Laura Brown (Moore) is a suburban housewife in California in 1951 with a loving but uninspiring husband and a young child. She is reading Mrs Dalloway and dreams of escape. In 1923, Virginia Woolf (Kidman) has been moved away into the London suburbs by doting husband Leonard Woolf so she can escape her demons and write her novel Mrs Dalloway.

Kidman’s is the hardest role, as her character comes with all the expectations Woolf devotees bring to her depiction. It is a remarkable performance, very unKidman-esque, less brittle than usual if a tad too grave and studied. And Kidman does not really look like Woolf, despite the make-up tricks. Streep, who was also terrific in the recent film Adaptation, is good if less flashy in this. The stand-out by a whisker has to be Moore but then she gets to do an ageing role, which is always impressive.

There are a number of other impressive performances. The child actors are stunning, especially Jack Rovello as Laura Brown’s son and Sophie Wyburd as the young Angelica Bell. Toni Collette has a fun cameo as a 50s housewife, Stephen Dillane is utterly convincing as Leonard Woolf and we could have seen more of Alison Janney as Streep’s live-in lover. Harris unfortunately is not at his best and his dying poet role is a bit of an AIDS caricature. We could also have done without the Philip Glass score and its minimalist distracting chatter.

This is intelligent and clever, elegant and nuanced and, mostly, moving cinema, due mainly to the Laura Brown story and its reverberations backwards and forwards in time. If there is an element of dissatisfaction, it is in the surprising lack of rage in the main women characters. One wonders where a female director might have taken it.