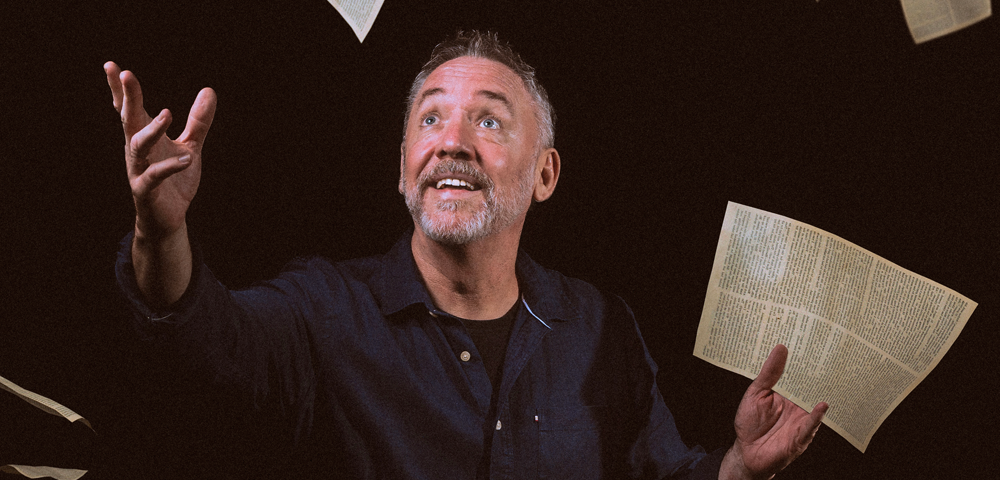

Life lines: John Marsden’s autobiography

You should be asking me about the Milat thing, John Marsden says between courses. We’re sitting in a restaurant in East Sydney that has served him as a kind of city lounge and dining room over the years, and he’s raised a topic that has been in my mind since we arrived.

Marsden’s book is called I am what I am, which is a camp reference, of course. But it also points to his frankness and the fact that he is, by his own admission, controversial and aggressive. The Milat thing he’s referring to has already appeared as a book extract in the Sydney Morning Herald and relates to an early Ivan Milat rape case.

In the early -˜70s Milat was charged with raping and terrorising two young women in the Belanglo forest. Marsden, acting for the accused, happened to see the women at a gay nightclub sharing a lot of intimacy the night before the trial.

In court the next day he raised the issue with one of the women, suggesting her homosexuality might have been a contributing factor in what happened with Milat: Crying and under stress, he writes, she ended up agreeing -“ and, in that moment, I knew we had won. Juries in those days were extremely prejudiced against gays and lesbians, and on top of that, we had put into their mind the possibility that the sex may have indeed been consensual.

I assure Marsden I intend to ask him about it. I explain I was leaving it until last (an old and obvious journalist’s trick) in case it led to an argument.

In his book Marsden says he’s not proud of using the women’s sexuality, but doesn’t think he had any choice. So does he have any regrets about doing it now?

Of course I have regrets, he says. Of course I do. And of course in today’s society the jury is not as anti-lesbian and gay as it was then.

They walked into a gay bar and they were openly kissing and cuddling etc. The next day I asked one of them, -˜Are you a lesbian, and did you encourage him because you wanted to try straight sex?’ This is a horrible thing -“ I’ve got a gay sister who’ll freak out. But in those days it wasn’t the same politically. No-one objected. No-one said anything.

It’s hard to imagine a man who has suffered so much for his homosexuality turning on a lesbian in court. But that is the lot of a lawyer, Marsden says.

But Marsden does know about suffering. He was targeted by the Wood Royal Commission into paedophilia, then subjected to two different current affairs programs accusing him of picking up under-age rent boys at The Wall for sex. The ensuing defamation case ran from 1995 until 2003 when Channel Seven paid him an undisclosed sum.

They were dark days, he says, when some of his oldest friends supported him and others turned away. He names them: Clover Moore, who did not give evidence at his trial. The Sydney Star Observer, who obtained legal advice not to meet with Marsden’s legal team before giving evidence.

I didn’t think I had the support of the gay community that I should have had, he says.

I had the support of the leaders of the gay community -“ people like Richard Cobden and Stevie Clayton, but not the wider community. I think there’s a lot of fear out there, people thought if they were seen to be supporting me they would be tainted also.

His legal practice (which is one of the Star‘s longest-running advertisers) lost business -“ 20 per cent from the straight community, 50 per cent from the gay community.

Two of my friends used to write letters to the Star supporting me, and then they’d get phone calls from other gay people calling them paedophile lovers, he says.

There was an enormous fear. That fear probably changed when the allegations were made against Michael Kirby. [But] I was very critical of the support Kirby got. I went publicly out and supported him, and he was the first person to come out and support me, within weeks of the program going to air. But I was cranky at the gay community -“ they supported him when they had turned their backs on me.

Marsden forgives the men who made claims against him, but that’s not because of his Catholicism (Marsden is a practising but non-Rainbow Sash Catholic, in his own words). It’s more to do with understanding the desperate lives they lead.

There’s not one of those people who made allegations against me that was living a reasonable lifestyle. Most of them had been tremendously abused as young people and I felt very sad for them.

All of Marsden’s life is in the book -“ his sexual relationships, his faith, his early experiences with beats, his community work in Campbelltown, his suicidal thoughts and his battle with cancer. He says he finds the final copy hard to read.

He hopes it will become a historical text for the gay community.

People don’t know what we went though, he says. They think Mardi Gras just happened. They think there was always a counselling service and always an Oxford Street. Many gay people my age are lonely men.