Sex workers in Australia say police are the last port of call when they need help

Sex workers have always had a tenuous relationship with the police. Jesse Jones spoke with sex workers about the law, their experiences with the police, and what needs to change to make their workplaces safer.

***

Imagine if you were assaulted at work, and your attacker was able to receive a lighter sentence just because of your job.

That’s exactly the situation that existed in Victoria until two years ago, when sentencing guidelines were finally updated to remove leniency for offenders who raped sex workers.

Queer sex worker Jane Green, from Victorian sex worker organisation Vixen Collective, says the old guidelines were among the many barriers that often stopped workers from seeking help from the police when they were victims of crime.

“Treatment in the courts has been and remains a massive barrier—people often don’t even consider going there,” she says.

“It’s not just sex workers who are operating outside of the licensing system—registered escorts and brothel workers are reluctant to go to the police because of the perception that they’ll be treated badly.”

Sex workers in Australia work in brothels or as independent escorts, either street-based or from their own premises.

The work settings deemed legal vary around the country, and some states have specific licensing and other regulations.

Workers have a longstanding, uneasy relationship with the police, and those who are not cis women often do private and street-based work because of the limited number of brothels that accept them, leading to police targeting and discrimination.

Green says the answer to better relationships between police and sex workers isn’t simple, but it starts with treating sex work like any other job.

“Decriminalisation won’t make everything perfect overnight, but it’s an important first step in making sure we have the same rights as other workers,” she says.

“We have to take that step.

“Police attitudes don’t change overnight, but they’ll never change unless we have decriminalisation.

“Stigma is the hardest thing to shift. But we’ll never get to the point of starting to shift it unless we start treating sex work as work, and treating sex workers as other workers are treated.”

Kelly*, a Victorian-based sex worker, has interacted with the police a number of times.

On one occasion, a Victoria Police officer and an Australian Federal Police officer visited a brothel where she was working, “looking for Asian sex workers” and information about “gangs and guns”.

“Nice stereotypes they pulled out of a hat,” she quips.

Kelly also had to call the police herself on one occasion because of violence against workers that was being perpetrated by a manager.

“He was employed to be the ‘enforcer’ on the floor each night,” Kelly says.

After many attempts to contact the relevant regulator, Consumer Affairs Victoria, Kelly says she resorted to contacting the police.

She says the officer she spoke to wasn’t forthcoming with information about her workplace rights or what, if anything, would be done about the complaint.

“I never heard back from them,” she says.

“Calling the police is always the last port of call, because the police are incredibly dangerous for sex workers, as regulators. And there’s that fear of losing your job.”

Kelly has also dealt with police when accompanying other sex workers who have needed to report sexual assault.

“[Police] equate it to shoplifting, and refuse to take the report,” she says.

Kelly says many sex workers are afraid of approaching the police to report crimes against themselves.

“They’re frightened that they’ll get in trouble or it won’t be taken seriously,” she explains.

Those who are working outside of the licensing framework, such as by working on the street or not having a licence number, may also fear legal trouble themselves if they approach police.

“That’s a big problem in Victoria, that the police are a [sex work] regulator,” says Kelly.

Some Victorian sex workers say that working under the licensing framework, where work outside that framework is criminalised and private escorts are required to register with the government, is even worse than working in places that totally outlaw sex work because of the extreme complexity of the laws.

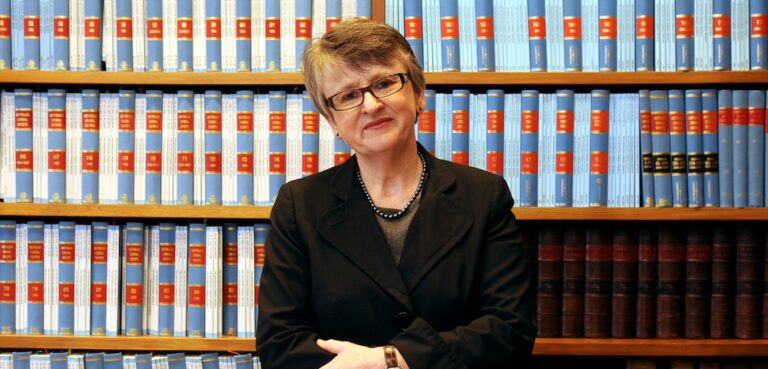

Jules Kim from national sex worker organisation Scarlet Alliance says sex work should be recognised as work, and workplace issues should be managed accordingly, instead of under a criminal framework.

“We should be working through an occupational health and safety lens rather than a criminal justice lens,” she says.

“Because our work is currently being regulated within a criminal justice framework there are limited avenues for us to pursue workplace rights, and crimes against us aren’t taken seriously.”

Under the criminalisation of sex work, in most parts of Australia where it is regulated by police, Kim says workers are subject to unwarranted “surveillance and entrapment”.

“In Queensland and Victoria, the police actively use entrapment,” she says.

Examples include police calling workers to request services considered illegal within those states, such as condomless oral or threesomes, and then laying charges if the worker agrees.

“It can be extremely difficult for sex workers to navigate due to the complexity of laws around sex work that differ between states and types of sex work,” adds Kim.

Such entrapment can disproportionately affect marginalised workers, such as migrant workers with limited English, who may not know what they are agreeing to.

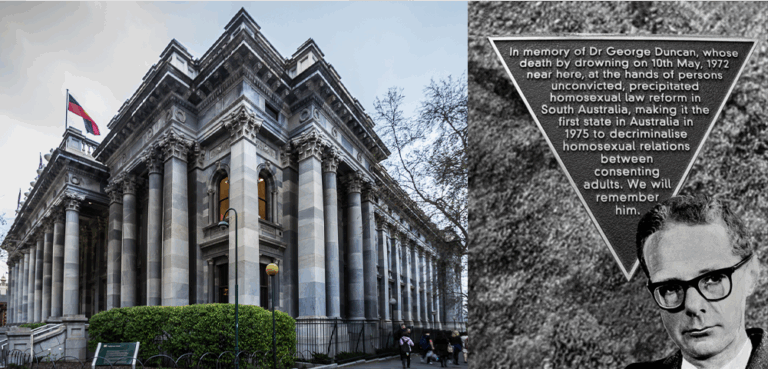

In Western Australia and South Australia, where most forms of sex work are deemed illegal, police may use the fact that someone had condoms as ‘evidence’ that they were working.

Kim says LGBTI sex workers can be disproportionately harmed because of the multiple levels of discrimination they encounter.

Indigenous sistergirl sex workers in particular have reported very poor treatment by clients and police alike, at the intersection of transphobia, racism, and ‘whorephobia’.

Like most advocates, Kim calls for full decriminalisation of sex work to make working conditions safer.

She says removing laws that restrict sex workers from operating in their own homes, or on the same premises as another person, would improve worker safety.

Decriminalisation is also a step towards treating sex work as a normal job and fighting the stigma that leads to poor treatment.

“Our work is work,” Kim says.

“Like all workers, we can have bad employers or bad clients—it’s just normal to any job.

“There is movement happening [towards decriminalisation] but it’s just incredibly slow.”

*Not her real name