The legacy of Michael Glynn

A SYDNEY without a legion of LGBTI media outlets is hard to imagine.

In 2016, there are so many options to source news about the community – and not just from traditional ‘pink media’ organisations like the Star Observer.

Now even mainstream news companies have resources dedicated to reporting LGBTI issues.

But 37 years ago that was not the case. Not until an opinionated American emigrant by the name of Michael Glynn changed everything forever.

It was on July 6, 1979 when the first edition of what was then known as The Star was distributed in Sydney.

“For me, I guess, the Golden Age of the gay/lesbian print media will always be Michael Glynn’s Star,” Craig Johnston, former City of Sydney councillor and founder of the Gay Rights Lobby, wrote in a dedication to Glynn.

“(It) was entirely maverick and unpredictable – except for its unshakeable commitment to gay power and community development.”

In 1979, homosexual sex was illegal, Sydney’s gay and lesbian community was still reeling from vicious police attacks during the city’s first Mardi Gras the year before, and there was a wave of political momentum to fight for equal rights.

The Star was what Glynn hoped would be his contribution to “the building of the gay movement and the growth of gay consciousness” and he certainly wasn’t afraid to ruffle the feathers of advertisers, politicians, friends and decision makers – no matter the cost.

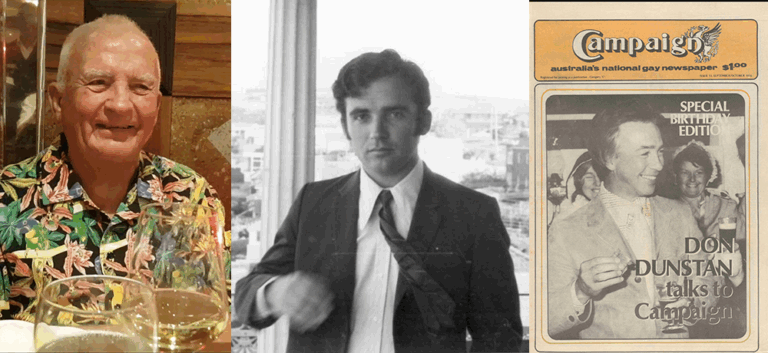

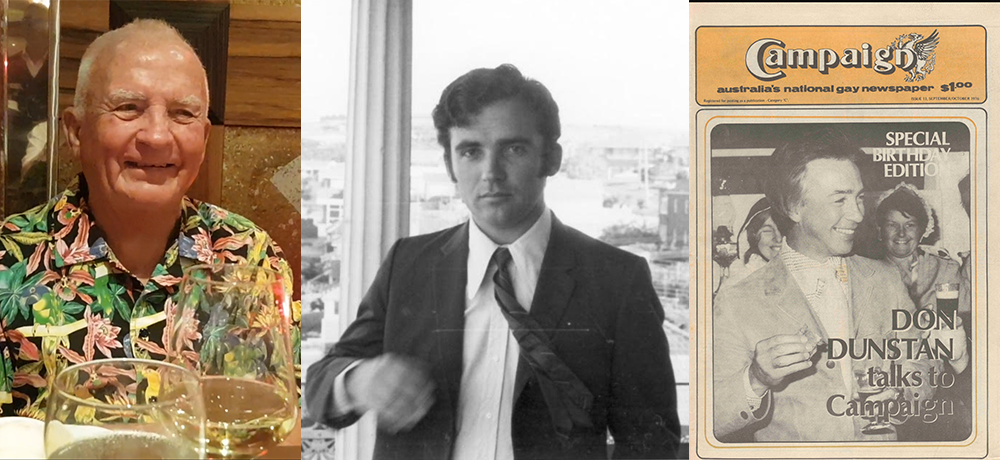

“Anyone who knew Michael was a friend or a foe,” Alan Goodwill, a good friend of Glynn and original staffer at the paper says.

“He was very different business wise, he was stubborn and pigheaded, he put people off him. Very few maintained a business relationship and friendship with him, it was one or the other.”

Born in New Jersey, Glynn was always destined to shake things up once he arrived in Australia in 1970.

This was a man who once shared a dance floor with disco queen Donna Summer at Studio One, worked for Robert F. Kennedy, studied music and psychology, and lied his way across many kitchens to eventually become a professional chef.

In one of his final interviews, Glynn told Larry Galbraith – in a recording which is now a part of the Pride History Group’s 100 Voices project – that his desperation to get out of America was what led him here when he was 22.

“I was in Boston and I was looking around for some- where else to live,” Glynn said.

“My growing up time in the United States was filled with John Kennedy being assassinated, Martin Luther King being assassinated… and I guess the last straw for me personally was Robert Kennedy’s death.

“That hit me really hard. I just realised I wanted somewhere better to live.”

In 1979, after being a teacher for a few years – a career he “just fell into” – Glynn saw a gap in Sydney’s market, and cobbled together what was to be the first edition of The Star in his flat.

It started off as a business and entertainment listing for the gay community but by November was a fully-fledged newspaper, reporting on important issues.

“I was tired of a lot of things that went on in this town… There was really nothing much exciting happening in Sydney,” Glynn told the Campaign newspaper in 1981.

“I felt (there was) a very strong need for a newspaper – something that was geared toward gay news. I think in a small way Sydney Star has helped to make Sydney more interesting, a more lively place to be.”

Goodwill agrees the weekly distribution of the publication was always a hot time in the city.

“His legacy started with foundation of the community paper,” he says. “People would sit in bars waiting for people to deliver them.

“It had a wonderful section of personal ads with different codes for what people were looking for. The personals were a thing a lot of people engaged in.”

Glynn used The Star to campaign for issues he was passionate about such as law reform, and often was the only media outlet to report on things like the police raids on gay clubs and the increase in bashings.

Only a few days before its second birthday in 1981, The Star was the first news organisation in Australia to report on what was described as a ‘new pneumonia linked to gay lifestyles’ which, as we now know, was the start of the global HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Often accused of being anti-camp, anti-drag and anti-women, Glynn vehemently denied such claims. He said he just wanted to teach gay men they could be men without being “effeminate”.

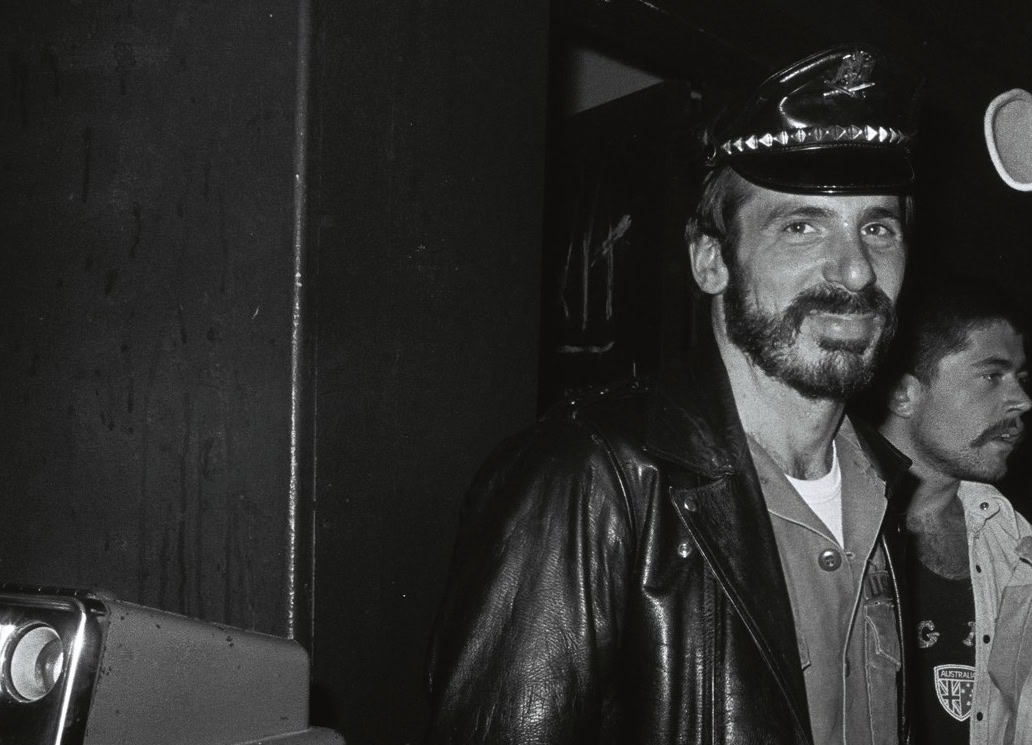

Glynn was a proactive member of the community, and helped found both the Gay Business Association and the AIDS Action Committee. He also recruited athletes for the first Australian team to compete at the Gay Games, and helped establish the Mr Leather competition, whose inaugural winner Patrick Brookes would go on to be named Mr International Leather the same year.

Glynn also helped coordinate street patrols on Oxford St to protect people from targeted physical attacks.

David Beschi opened Sydney’s first gay leather bar and also financed The Star’s transition from a booklet to its newspaper form.

“Michael came there very often… he was never outrageous, he never wanted to portray himself as just ‘a Leather Man’,” Beschi explains.

But in 1984, things took a turn for the worst for Glynn.

He sold The Star to its employees, but never saw a cent from the sale, which left him destitute.

Then, like many gay men of that era, his partner Steve Cribb was diagnosed with AIDS and Glynn seroconverted not long after. In 1986, Glynn was left inconsolable after Cribb passed away.

Having not received any money from the sale of The Star, Glynn was forced to live in his car with his two great danes, Eva and Toby.

“He was never paid what the newspaper was worth,” Goodwill explains.

“He had nowhere to live, he was living out of the back of his Kingswood station wagon with his dogs.

He would park at Centennial Park because he had to be somewhere the dogs could walk.

“Michael befriended lots of the rangers in the park… and they would warn him of where there would be patrols of a night. They’d say ‘stay out of the Randwick side tonight’,” Goodwill says.

“When Steve died he went right off the deep end. He wasn’t the same person for a long time.”

Friends helped Glynn move into a government flat in Glebe where he lived until his death on July 10, 1996.

There was a perception for a long time that Glynn died a lonely soul, but Beschi and Goodwill disagree.

“The community rallied around him,” Goodwill explains.

“He didn’t have money to pay for his funeral, so people came from all over the community to buy something personal from his apartment, whether it was a hat or his leather jacket.”

Dominic O’Grady was a journalist at the Sydney Star when Glynn died and went on to write a PhD on his life, titled Preaching to the Perverted: the life and times of Michael Glynn.

“In telling the story of Michael’s life, you also tell the story of Sydney’s emerging gay community,” O’Grady says.

“I love what Michael Glynn’s story represents. It’s a story about empowerment and the capacity of narrative to build community and to change a system that sucks.

“Glynn pissed a lot of people off because he was opinionated and often angry. But he was also loyal to those he loved, and he was determined to the fight for equality and sexual freedom.

“The legacy we’ve inherited from him is invaluable.”

Today we have lost a great brother and advocate for our community. 10 years ago I read through archives of the Sydney Star Observer for articles on the state of LGBTI rights and how to lobbying/influencing politicians and his name popped up a lot. Also 10 years ago today I have personally become an ally and activist of the LGBTI community. R.I.P Michael Glynn you will be missed. I have personally never met the man, but his spirit is with all of us LGBTI activists, helping achieve full equality for the LGBTI community and release the shackles of oppression.

Great article on a great man , an icon in the Sydney gay scene in the late 1970’s / 1980’s .

I remember him very well as I lived with my partner at 344 Crown street at the time. These were the days when the gay scene in Sydney was opening up . There was hope in the air and we felt we were getting somewhere after years in obscurity and oppression.

Michael helped with the publication of the newspaper we eagerly waited to read every week.

We need to remember him with a plaque with his achievements and name somewhere on Crown street .

Yves Hernot

Michael was a true leader in the community. I worked with him at the Star in 1983 and remember his two dogs well. Great man and admired by many.

Michael was a force to be reckoned with. Both he and Steve Cribb made wonderful contributions to the queer community and the HIV community.

Just two thoughts to add in memory of Michael Glynn.

His ancestry (if I remember correctly) was part American Indian.

I answered his call for anti-violence street patrol initiative volunteers and we did that as a community service for a time–shortly after it ceased (within weeks), there was a murder in a side street just off Oxford Street.

Such was his forethought and mindfulness.