The long march to equality

IN 1951, well-known author, choreographer and actor Noel Tovey was arrested charged — as put by the judge — for the “abominable act of buggery” at a party held by famous drag queen Max Du Barry.

The media attention was brutal, with headlines slandering the 17-year-old on a daily basis.

Tovey was given a two-year good behaviour bond but said he was coerced into a confession.

“It was very difficult for me, after the conviction I had a lot of problems,” Tovey said.

“My friends couldn’t be seen talking to me because I was a known criminal and they could have been charged with consorting.

“My mother told me that I was illegitimate.”

While Tovey’s case in 1951 attracted attention — the wrong kind, of course — it wasn’t until after England and Wales decriminalised homosexuality in 1967 that the winds of change came to Australia.

The first politician to attempt to change the laws that criminalised male homosexual behaviour was former South Australian Premier Don Dunstan. As the state’s Attorney-General during the mid-1960s, Dunstan had a law reform bill drafted but it was abandoned due to a perceived lack of public support at that time.

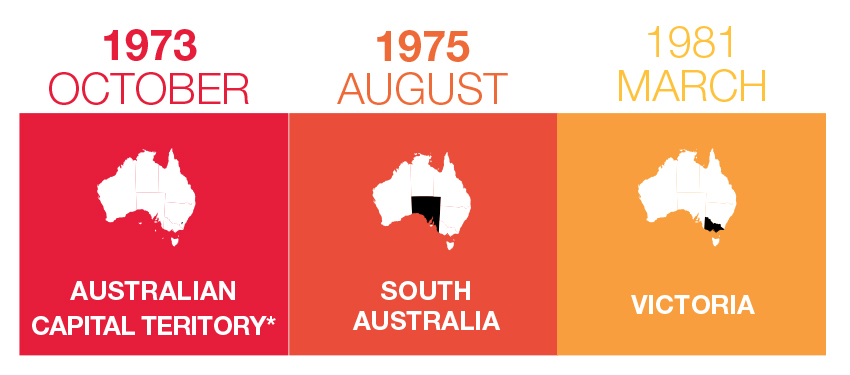

Instead, it was the ACT that became the first jurisdiction where homosexual conduct was decriminalised, thanks to the efforts of lobbyists. The 1973 motion in favour of decriminalisation was introduced in the House of Representatives and was sponsored by Labor MP Moss Cass and Liberal Senator John Gorton, who was Prime Minister between 1968 and 1971. The successful motion passed 64 votes to 40, but it was not ratified until 1976 by then-Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser.

Former Labor ACT senator and current Age and Disability Discrimination Commissioner Susan Ryan was one of the key drivers behind the reform.

“[By 1975] I had come to the view that all people should be free to express their sexual identity and that the case for criminalisation of male homosexuality was wrongly based, outdated and imposed an intolerable and unfair burden on male homosexuals,” she said.

“I was convinced that the law should be changed to provide equal rights as between homosexual and heterosexual people.”

Ryan recalled voices that were “totally hostile to homosexuality”, but there was also a lot of support to make the the motion pass successfully in 1973.

“During my campaign for the Senate in November-December 1975 I was frequently attacked by conservative groups and individuals for my support for decriminalisation of homosexuality, and indeed I was accused of supporting pedophilia and incest, both of which accusations of course were total hostile fabrications,” Ryan said.

“When [homosexuality was decriminalised] I regarded it as an important, if belated, advance in recognising people’s fundamental rights. I was pleased that I had played a role in securing this important reform.”

South Australia was the next state to tackle homosexual decriminalisation, following on the efforts of Don Dunstan and community anger from the death of gay academic George Duncan — who drowned after being thrown into the water by police at an Adelaide beat.

Several reform efforts were thwarted until a re-elected Duncan introduced a bill in August 1975, and after numerous readings it was passed on the same day by both houses.

South Australia had become the first state to not only decriminalise homosexuality, but abolished gross indecency and solicitation laws. It also equalised the age of consent for homosexual and heterosexual sex.

Despite calls for law reform in 1975, the Victorian LGBTI community would have to wait until 1981 for decriminalisation to pass on Spring St.

Using his experience gained from campaigning for homosexual law reform in the UK, Jamie Gardiner returned home to Victoria in 1974 and became involved with the movement.

The first draft of a reform bill was prepared by Labor MP Barry Jones but it was withdrawn after it was considered inadequate.

Following the first Australian Homosexual Conference in Melbourne in 1975, support for reform continued to grow from a range of LGBTI and non-LGBTI groups — including some religious ones.

Gardiner said police crackdown at beats were considered to be “arbitrary and inconsistent” and usually involved entrapment, adding momentum to the movement.

News of numerous arrests at a Black Rock beat in 1976 gave supporters an opportunity to parlay the police activity into a campaign that attracted media attention.

“[Police crackdowns were] certainly very important in creating opportunities for media campaigns and embarrassing the government and stimulating action,” Gardiner said.

Activists were informed in 1976 that then-Premier Rupert Hamer had asked the Attorney-General to prepare a report on homosexual law reform.

Thanks to the support from journalists John Rentsch and Gerry Carman, reform was given a prominent and legitimised voice in the public sphere.

“This was important, and a valuable resource. I can’t really speculate on what would have happened had we been unable to find any,” Gardiner said.

Despite a formal campaign launch following a 1977 favourable poll in The Age, reform would not be passed by Victorian Parliament until December 1980. The law came into effect in March 1981.

On why addressing decriminalisation was something he pursued in parliament, Jones said: “The general issue of discrimination — whether race, gender, class, sexuality, education — was what involved me.”

He added that he admired the leadership of the former South Australian Premier on this issue.

“I persuaded my Labor colleagues to let me introduce a Private Member’s Bill in [the 1976] Legislative Assembly, decriminalising homosexuality,” he said.

“Similar legislation was proposed at the same time in the ACT and South Australia. I admired Don Dunstan’s courage.”

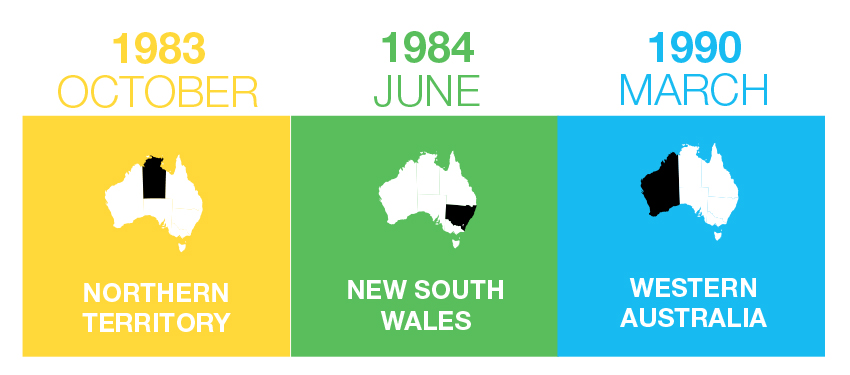

The process of homosexual law reform in Northern Territory started soon after the territory had become self-governing in 1978, thanks to the sustained efforts by the LGBTI community and advocates. Not wasting time, in 1983 the territory government passed the Criminal Code that made acts between consenting men in private legal.

NSW may be considered the birthplace of Australia’s gay liberation movement, but it was not until 1984 that consenting homosexual acts were no longer considered an offence.

Although an unsuccessful effort was made in 1978, momentum towards reform has been attributed to former Premier Neville Wran’s decision to amend rape laws and have them use gender-neutral terminology.

An inconsistency between the new law and an existing section of the Crimes Act that referred to homosexual activity paved the way for a political campaign to bring about decriminalisation.

Several bills were introduced to address reform but they were all defeated, with some blaming the influence of the Catholic Church within NSW Labor.

After several raids at Sydney gay sex club Club 80 — where 27 men were arrested on varying charges in 1983 — media and public attention was once again directed back to the issue of reform.

It was next addressed in 1984 when Premier Wran announced he would introduce legislation to decriminalise homosexuality to be voted along party lines. It passed successfully through both houses of NSW Parliament in May 1984.

Western Australia and Queensland were the next states to address reform in 1990 despite numerous attempts since the late 1970s.

Following South Australia’s lead, the Attorney-General had attempted to introduce a similar bill in Western Australia but it was defeated. After several further attempts over the years, success was finally achieved in 1989 in the form of the Law Reform (Decriminalisation of Sodomy) Bill, which was implemented in 1990.

Meanwhile, Queensland had a reputation of being resistant to homosexual law reform, mainly due to the leadership of former Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen and his staunchly-conservative views.

While other states were slowly passing law reform, Queensland’s LGBTI community was being persecuted. Media and public attention was finally drawn to the issue after some notable police arrests, including the infamous arrests in the western Queensland town of Roma in 1989. Despite heated protests, the government indicated there would be no change in the treatment of “sexual deviants”.

However, with the election of the Wayne Goss Government in 1989 came the announcement of a review of Queensland laws on homosexuality.

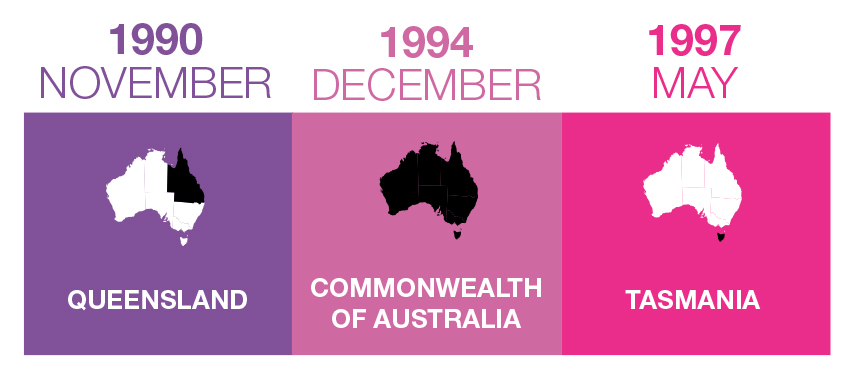

Soon after, a Criminal Justice Commission review recommended the removal of all references to homosexual sexual conduct from the Criminal Code, and by November 1990 Queensland Parliament finally voted in favour of the decriminalisation of homosexuality.

Similar to other states, Tasmania followed South Australia’s lead in 1975 but despite the efforts of activists — including the very public “coming out” of former Greens leader Bob Brown on television — the bill failed to reach the state’s parliament.

Any other plans to address reform were abandoned by the government and homosexual laws remained largely in place until 1987 when gender-neutral language was introduced into the Criminal Code Act, which led to a similar scenario as NSW.

As a part of its strategy to address HIV and AIDS, the government attempted to address law reform — which included wording in the bill’s preamble referring to “homosexual promiscuity” — but it failed to pass the upper house in 1991.

It would then be a long wait for Tasmanians to see any change in the state’s laws.

In 1994, the Tasmanian Parliament’s refusal to decriminalise homosexuality led to the Federal Government passing a bill that legalised sexual activity between consenting same-sex adults throughout Australia.

An attempt at reform in 1996 was again defeated in the Tasmanian upper house, but the Australian High Court agreed to hear a case against the State Government brought on by Rodney Croome, who is now the national director of Australian Marriage Equality, and the Tasmanian Gay and Lesbian Rights Group.

After numerous failed attempts to have the case of Croome v Tasmania in 1997 struck out, the Tasmanian Parliament eventually repealed Criminal Code provisions about homosexual activity.

With Tasmania finishing Australia’s journey to full decriminalisation, attention has been shifted to other LGBTI rights that needed to be achieved: marriage equality, surrogacy, adoption, equalising age of consent, expungement of historical convictions, and more.

Despite moving to England in 1960 to pursue a career in dance, Noel Tovey’s conviction came back to haunt him in professional circles — right up until Victoria became the first Australian state to expunge historical convictions of consensual gay conduct in October this year.

“Several of the boys [at her Majesty’s Theatre] went to the English choreographer and told her that they didn’t want to work with me because I was a notorious homosexual and that I had been in jail,” Tovey said.

“I’m happy to die knowing that I am no longer a criminal.”

**This article was first published in the December edition of the Star Observer, which is available to read in digital flip-book format. To obtain a hard copy, click here to find out where you can grab one in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, Canberra and select regional areas.

RELATED: REMEMBERING OUR PAST ALLOWS US TO LOOK TO THE FUTURE

Pride History Group’s Homosexual Histories Conference 2014, supported by the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives and the Australian Centre for Public History, will be held at UTS on November 28-29. Details: www.pridehistorygroup.org.au

Some rather dubious “journalism” here..

1. The ACT motion in 1973 was just that – a motion in the Federal Parliament (there was no ACT legislative body at that point) and It wasn’t enacting any law. So to say the ACT “decriminalised” it in 1973 is simply wrong.

2. The Prime Minister did not “ratify” the ACT law – the Attorney General did. And this was after the ACT legislative body was set up under statute.

3. The Commonwealth Government does not and never did have the power to directly make criminal law in regard to this issue. The 1994 legislation was an attempt to implement Australia’s international treaty obligations. It did not make law per se on the issue, but highlighted the incompatibility of Tasmanian law with Australia’s treaty obligations which no doubt led to the Croome High Court Case.

Get the facts right please SSO and don’t just copy/paste from Wikipedia!

Blair, you and the article are correct. It was a re-elected Dunstan Government but the Bill was introduced by the Attorney-General Peter Duncan. I often think that Duncan doesn’t get due recognition.

Slight typo:

” Several reform efforts were thwarted until a re-elected Duncan introduced a bill in August 1975, and after numerous readings it was passed on the same day by both houses. ”

Should be “Dunstan” not “Duncan”

What an excellent article, all current and future gay activists should read and brush up on the history in the past 40 years!

We still have a long way to go in 2014:

* Marriage Equality for the all of the Commonwealth of Australia!

* Adoption equality in NT, VIC, SA and QLD!

* Surrogacy equality in WA and SA!

* IVF access for single women and lesbians in SA!

* The “abolishment” of the “gay panic defence” (GPD) in SA and QLD!

* Expungement of gay sex criminal conviction records in QLD, NT, WA, TAS and ACT (only laws passed in VIC, NSW and SA)

The Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives’ 14th Australia’s Homosexual Histories Conference is on in Sydney THIS Friday and Saturday, 28-29 Nov, presented by the Pride History Group in conjunction with the Australian Centre for Public History (UTS).

Program: http://camp.org.au/ahhc14/ahhc14-program-summary

Registration: http://www.eventbrite.com/e/australian-homosexual-histories-conference-2014-tickets-12541169977?aff=es2&rank=1

Love the pic used