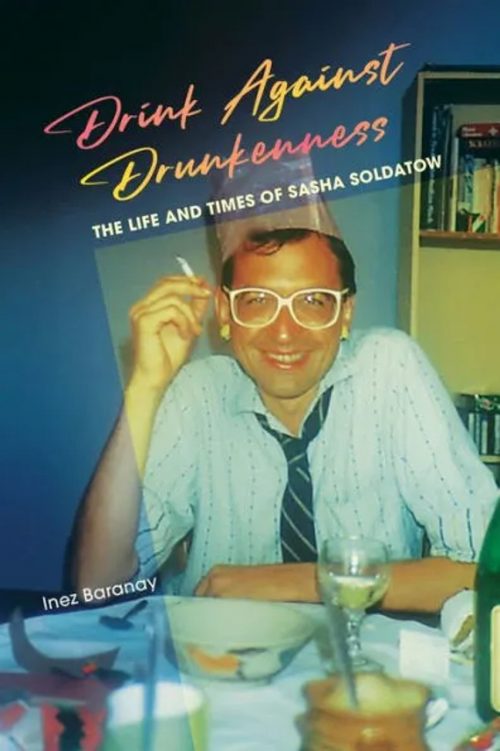

The Life And Times Of Sasha Soldatow

‘Why should I know about him?’ is the first line of ‘Drink Against Drunkenness – The Life And Times Of Sasha Soldatow’, a biography by Inez Baranay.

It’s a good question. Soldatow was not a famous person with a history of official achievements or recognition. Yet he had many talents including friendship, writing in many forms, publishing, drawing, playing the piano, gardening, cooking, falling in love and having intense sexual relationships, provoking and challenging, and especially having fun.

Baranay found the question answered during talks when the book was in its early stages. She writes: “Not only was Sasha one of the most unforgettable, influential, charming, infuriating, brilliant people they remembered, but he is also interesting in terms of the spirit of the times …”.

Those times included battles against censorship, the beginnings of what is today’s LGBTQI movement, Greens Bans and squatting that saved Inner Sydney, tenants’ rights, feminism, the prison reform movement and shifts in literature, performance and publishing, especially at the margins.

Friends And Lovers

Baranay resists simple explanations or conclusions about Soldatow’s character. Instead, she takes the reader on a journey through his life.

She draws on a rich resource of 56 interviews (because he died at 58, there are many people alive who remember him), 40 boxes of diaries, letters and documents in the Mitchell Library, and other documents including her own diaries and letters.

The result is not just a rich multi-faceted portrait of one man. We get to know friends and lovers, whose interviews she quotes; we read about activities and provocations that tell us about the times, but have previously not been brought to life in text.

Each main activity and period of his life has its own chapter, sometimes more than one. This means that the book should attract a range of interests including LGBTQI history and politics, the history of cultural politics in Inner Sydney, radical politics in Australia in the 1970s and 80s and the history of post war migration.

Coming Out In 1969

Sasha Soldatow was born in Germany of Russian parents after the Second World War. When he was two, his family migrated to Australia. He grew up in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne and attended Melbourne University. His politics were shaped on the streets during Vietnam War protests.

Baranay writes, “Sasha seemed to know as soon as it was a possible thought that he was gay, but in those days of silence, invisibility, illegality, criminalisation, widespread ignorance and prejudice, it wasn’t a thought that you could easily enunciate”. [p81] In 1969, he came out as homosexual to the world and his family in a Channel 7 interview filmed during a tiny protest in Melbourne’s CBD in 1969. As was not unusual in those days, his mother found his revelation distressing and told him he was mentally ill.

In 1972, Soldatow moved to Sydney attracted to its anarchist tradition, the group known as the Sydney Push, and a radical movement that used publishing as the form of action against censorship and disrupting silences. In other words, ‘Being Free by Acting Free’.

In his first eighteen months in Sydney, he squatted in threatened houses to stop demolition in Victoria Street, Kings Cross. That’s how I met him. In his first eighteen months in Sydney, we squatted in threatened houses to stop demolition in Victoria Street, Kings Cross. We were both publishers of Scrounge, a small grassroots roneoed publication that was a journalistic account of events connected with radical politics at that time.

Soldatow Was At The First Mardi Gras In 1978

His interest in small scale self-publishing continued but his inclination was towards creative writing. Over his life, he published six critically acclaimed books, many stories, essays, and reviews, regular columns in the gay press including Sydney Star Observer, and pamphlets of poetry and polemics that he also illustrated, designed and published.

He published a rigorously researched essay on Harry Hooten, a radical poet of the 1950s. His close friend and supporter the filmmaker Margaret Fink regarded this as his best work.

Soldatow was at the first Mardi Gras in 1978. At a protest outside Darlinghurst Police Station in the following days, his close friend the poet Pam Brown remembers his sound advice not to retreat in the face of police on horseback.

But for him, gay liberation was never the main fight. It sat within a much broader critique underpinned by broader ideas of liberation informed by the notion of the ‘personal is political’ and the ‘politics of everyday life’.

The Adventures Of Rock And Roll Sally

In 1983, he published a memorable pamphlet ‘What is this gay community shit?’. Baranay interviewed someone who in 2019 was drawing on its critique of the corporate influences on the Mardi Gras in a Queer Reading Group in 2019. Like many revolutionaries of the 1960s, Soldatow was attuned to the capacity of capitalism to absorb radical dissent.

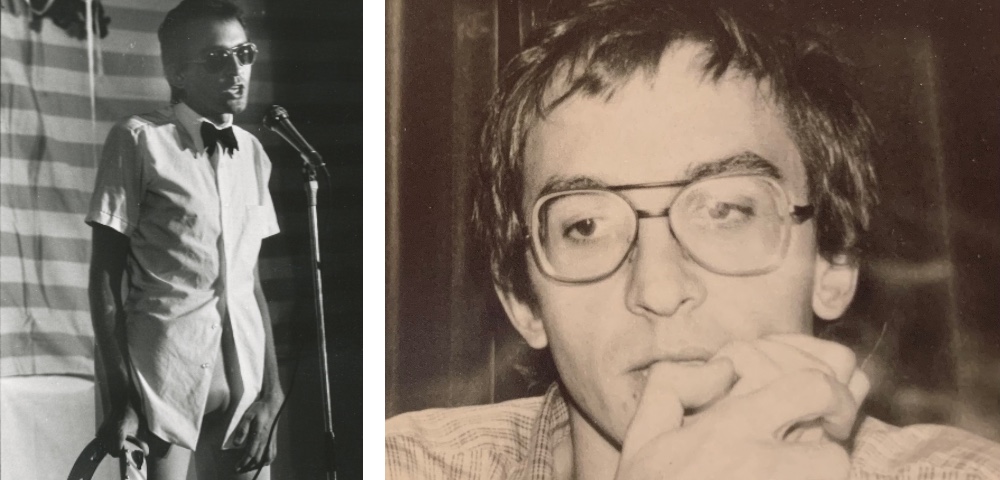

For Soldatow, writing was often mixed with performance. In his own words, “Performance was something that we all did at that time.” Many were impromptu events, often involving nudity. But there were more organised events. In 1983, the Performance Space, a dedicated contemporary arts space in Surry Hills was launched. Soldatow, Pam Brown and Amanda Stewart (who was a leader in the radio program Gay Waves) read poetry together there.

One of Soldatow’s best remembered creations was the Adventures of Rock and Roll Sally which was a suite of poems published in different format and editions as well as performances with accompanying posters.

Wearing tiny denim shorts and platform shoes, his hair bleached, the electrifying performance challenged boundaries. As a friend who sometimes performed with him remembers, “he turned drag on its head. He was informed by feminism and … the commercialisation that was seeking its way” into the gay movement.

A Generous Friend

Soldatow was a generous friend and mentor. He always had time for engaged conversations. Margaret Fink’s now adult children remember him as an accepting and entertaining gay uncle.

Even those who knew him will find surprises in this book. Soldatow was able to use the knowledge of Russian language and culture that he developed in his youth to produce very serious Russian translations. His version of the Russian poet Anna Ahmatova’s work Requiem was performed at the Adelaide Festival and the Sydney Opera House as part of Sandakan Threnody, an original composition by Jonathan Mills.

The poem deals with the suffering of women during the terror of the Stalin era. Mills told Baranay, “I think the way of conveying [the pain and silence in Requiem] was the complete command of the poetic, linguistic and translational dimension in which his work resonates….it was a very well-ordered garden in complete contrast to the disorder in most parts of his life.”

As the story progresses, the contradictions become clear. Soldatow actively embraced the margins yet cared about acceptance as a writer and was bitterly disappointed by rejection from bigger publishers and funders. Notoriously, he took legal action against the main literary grants body for continual rejection of his applications.

As it must, Baranay’s story incorporates Soldatow’s decline. Self-destruction, depression and addiction. Some of this was precipitated by a shattered hip bone caused by badly treated fall on ice while he was in Russia at the time when the Soviet Union collapsed.

I See

His life of partying, laughing, provocation and intense conversations faded. But his decline was not even. In the 1990s, he collaborated with a younger and now well-known novelist Christos Tsiolkas on Jump Cuts, a joint autobiography structured as dialogue in which it is not always clear which voice is talking.

Part of his last months were spent in social housing in Redfern. While he alienated many, good friends supported him to the end.

Soldatow died of liver failure in 2006. He was 58. On his instructions, his grave at Rookwood Cemetery carries his name, the years of his life and two words, I SEE.

His life as lived, and its literary products, recognised and performed the sexual and political contradictions of his times. The relevance of his political and creative works remains and this biography brings them to life for a new generation of activists.

Drink against Drunkenness – the Life and Times of Sasha Soldatow by Inez Baranay is out now in selected book shops. It will be launched by friend and co-author Christos Tsiolkas at Kinselas in Darlinghurst, Sydney on October 19.

If you want to attend the Sydney launch on 19 October please get your free ticket here. A Melbourne launch in November will be announced soon. Follow for news, reviews and more at: https://www.facebook.com/sashabiography