Note: This article discusses biphobia, including detailed examples. It also mentions suicidality, domestic, family, and sexual violence, genocide, deaths in custody, and attacks on trans rights. Please read with care.

Confession: I’m tired of visibility days.

For the past couple of years, I’ve felt an unexpected dread settle in as we get closer to 23 September. It feels wrong to admit, but a day that I once found joy in has started to feel hollow.

At first I thought it might be because I’m a bad bisexual (there’s no such thing). Then I thought it must be because I’m burnt out (there’s some truth to this). These days, I know it’s because I’m skeptical of visibility alone as a lens for bi+ experiences.

With Bi+ Visibility Day upon us again, many LGBTQIA+ organisations will share words of acknowledgement and affirmation to mark the 23rd. In anticipation of this, I find myself questioning how much visibility days actually create meaningful change for our communities. I wonder if we, as a community, will ever get to move beyond visibility as a dominant framing for our experiences. Who gets to be visible? To what extent is visibility safe? Does visibility change the conditions we live in?

Visibility and Whiteness

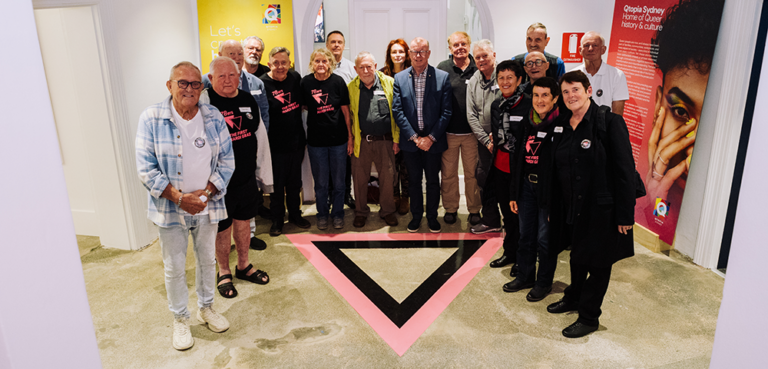

Many point to the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s as key points in time for bisexual movements, citing the proliferation of bisexual-focused organisations as pivotal in building the visibility of bi+ communities. While these are significant milestones that should be remembered, it’s also important to know that societal understandings about sexuality and gender have broadly been informed solely by Western perspectives and ideologies.

On this, Troy-Anthony Baylis has written, “The lived realities of colonisation have constructed a silencing force that mutes Queer Aboriginality”. Western conceptualisations have also dominated the language we use to describe diverse and marginalised sexualities, many of which have pathologising histories.

What does this have to do with visibility?

Ultimately, this means conversations about community histories are predominantly white, especially in so-called Australia. This grounds the origins of our movements and what it means to ‘be visible’ in whiteness. As a result, we fail to meaningfully include the way colonisation and racism have, and continue to, shape bi+ experiences. Often, it also means that white bi+ people avoid conversations about how we are complicit in white supremacy.

This isn’t to say that the work of bi+ movements from the 1970s to 1990s is bad or wrong. For so many it was lifesaving and this is something to celebrate. It does, however, call on us to remember that there is a relationship between the past and the present and to be critical of who gets to be visible, whose stories have been remembered, and whose have been sidelined or silenced.

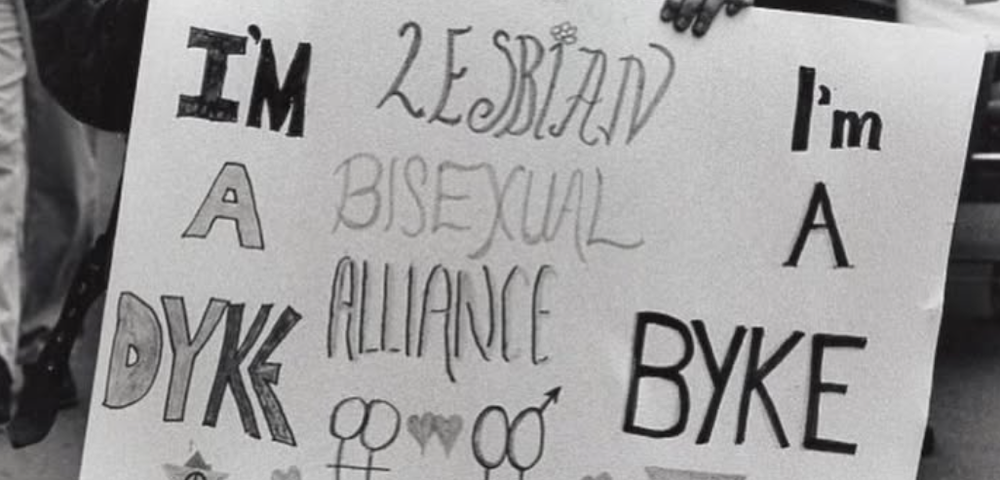

The Monosexual Rejection

In the 1970s, tensions surfaced between bisexual women and the lesbian feminist movement. Described as being driven by rigid rules and absolutes, this time period saw separatist politics framing bisexual women as “fence sitters” or untrustworthy because of their associations with men. This tension continued into the 1990s and still permeates queer experiences and discourse today (see also: the many, many takes about Jojo Siwa and Fletcher)

The 1980s also marked a deeply fraught period for bisexual movements, with bisexual men being regularly scapegoated in public discourse, falsely portrayed as vectors of HIV transmission beyond gay communities.

Both of these examples underscore what Kenji Yoshino has named an “epistemic contract of bisexual erasure” or a social contract between heterosexual, gay, and lesbian communities to produce and maintain a culture that erases bisexuality. According to Yoshino, one of the common interests between heterosexual, gay, and lesbian communities is that attraction to more than one gender disrupts status quo and subverts structures relying on a gender binary.

Throughout my time organising in LGBTQIA+ spaces, I have seen how Yoshino’s ideas play out in real time, the insidious ways that bi+ experiences are denigrated and denied. The ways that mainstream spaces forget we exist or hypersexualise us.

In this, I am led to think about the relationship between visibility and power. On the one hand, visibility can facilitate how we find each other and make connections, which has a positive impact on our mental health and wellbeing.

On the other hand, I wonder about how a reliance on visibility creates and perpetrates unequal power dynamics, asking for our existence and humanity to be recognised by people outside of our community. What does this mean for our autonomy? For how we make decisions about our communities? For how we celebrate who we are and how we love?

The Limits of Visibility

Some could argue that bi+ communities are more visible than ever, with an increasing number of people globally and in so-called Australia sharing they use labels like bisexual and pansexual to describe themselves.

And yet, bi+ people are still more likely than gay, lesbian and straight counterparts to have poor health outcomes. We are more likely to have an earlier average age of first homelessness and are more likely to have repeated episodes of homelessness than lesbian, gay, and straight people. We experience high rates of psychological distress, suicidality, and domestic, family, and sexual violence. We also experience discrimination and stigma from within LGBTQIA+ communities and from mainstream communities. These disparities are magnified for bi+ people who live at the intersections of multiple marginalised identities and experiences. On top of this, bi+ organisations and programs in so-called Australia are consistently underfunded/unfunded and are predominantly sustained by overworked (but passionate) volunteers.

Across these areas, bi+ visibility helps us to see ourselves and our stories reflected in social issues. This plays a role in finding support and in ensuring we don’t feel alone in navigating our experiences. While we shouldn’t underestimate the role this plays in building communities and in supporting our health and wellbeing, I think it’s important we are also honest about the limitations visibility brings us.

Visibility alone won’t change the cost of living. It doesn’t change deaths in custody. It doesn’t topple the corporations causing climate change. Neo-Nazis are marching in the streets, Israel is committing a genocide, the number of First Nations deaths in custody keep increasing, and trans rights are under consistent attack.

Challenging all of this is a lot. And it’s hard. And it’s necessary. It requires us to increase interconnectedness, to be critical of how we create change, to be defiant, to grieve and to love.

This doesn’t deny that visibility can be part of changing narratives. For many it’s an entry way into community and in understanding bi+ experiences. And yes, we can care about more than one thing at a time.

However, for us to change the conditions we live in, we have to reckon with the wider systems and structures that impact on our lives, such as monosexism, heteronormativity, cisnormativity, capitalism, racism, ableism and more. We have to think critically about how we form connections and how we engage in social change work. If we don’t contend with these, we will never create a world where bi+ people can live freely and joyfully.

Creating New Futures

Visibility offers recognition but it is not the same as liberation.

I’m not going to bend over backwards for people and organisations to merely recognise my existence. I’m tired of being grateful for crumbs.

What I want is for us to create more possibilities for a future that’s different from the status quo. More than ever, I’m curious about how we are showing up for each other, how we are loving and caring for each other. And how we can leverage all of this to build a kinder, gentler, and safer world. Bi+ visibility alone won’t get us there.

So here I am on Bi+ Visibility Day more sure than ever that flashpoints of acknowledgement and affirmation aren’t enough.

Maybe what I’m looking for instead of bi+ visibility is bi+ justice. How will you help us get there?

Amber (they/them) is a trans, genderqueer, bi+ community organiser, parent, and creative. They are a community organiser with Sydney Bi+ Network, a grassroots organisation dedicated to improving the wellbeing of Bi+ people across so-called Sydney through community building, education, and advocacy. Their work is centred around creating a just world where communities can be joyous and thrive.

Leave a Reply