It’s not about censorship

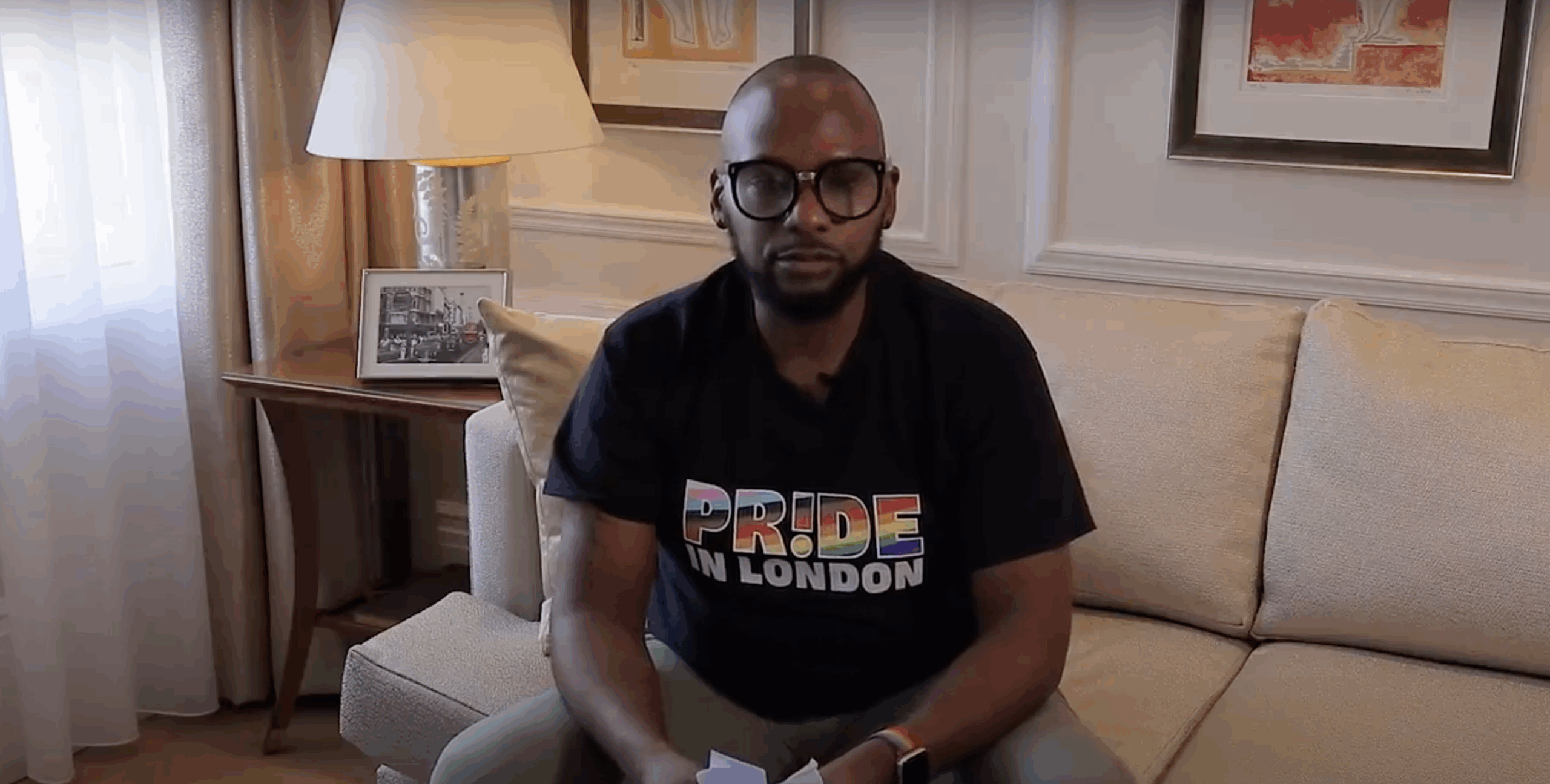

We invited Rob Cover, Professor of Digital Communication at RMIT University, to respond to an opinion piece written by Jennifer Oriel regarding new reporting guidelines released by the Australian Press Council.

In November 2019 the Australian Press Council released guidelines for reporting on gender and sexual diversity, updating the general guidelines which inform journalists about the impact of bias, slanting and use of terminology about minorities.

The Press Council guidelines are a welcome response to the need for journalists to be aware of the health and mental health implications of biased or under-researched reporting on gender and sexual minorities, and of the role played by contemporary journalists in maintaining damaging social opinions or, conversely, in fostering social change towards greater inclusivity and acceptance of minorities.

In a move that should be widely celebrated, it has been unfortunate—although not unexpected—that The Australian should continue its routine anti-trans and anti-minority prejudice in another anti-queer opinion piece by columnist Jennifer Oriel.

As is often the case with The Australian’s commentary on sexuality and gender, Oriel’s piece is based on gross distortions of the role of the guidelines, on the political history of gender and sexual inclusivity, and on current developments in gender identity in Australia. Rather than factual observations, the attack on the new guidelines is unduly alarmist, dog-whistling for conservative and alt-right hysteria, and defensive of views that are no longer relevant to the Australian mainstream.

“guidelines are based on very standard journalistic ethics”

Oriel argues that the guidelines will result not in better reporting but in press censorship.

The Press Council, however, has been very clear that they are designed to “promote informed reporting” and to “assist journalists and publications to improve standards of reporting so as not to exacerbate, even inadvertently, particular concerns faced by such persons.”

The new gender and sexuality guidelines are based on very standard journalistic ethics. They advise, for example, that reference to a person’s diverse gender or sexuality should be relevant to the story rather than salacious, that those references should be reported accurately and that stories about sexual and gender diversity should be based on “credible and relevant research and statistics.”

What Oriel avoids mentioning in her alarmist claim that Australia is “sleepwalking into a state of political censorship” is that press guidelines are not rules for censorship but designed to reduce instances of injury, unhealthiness, hurt and pain among a readership and a broader society, and help protect media outlets and journalists from mistakes, factual inaccuracies about minorities and lawsuits.

There is, of course, a genuine fear of these guidelines by outlets such as The Australian which have, for many years now, sustained an anti-diversity and a particularly vicious anti-transgender line across its opinion and political writing. Guidelines that outline best practices of ethical reporting actively challenge The Australian’s righteousness in their campaign against contemporary gender and sexual diversity as seen across the marriage equality debates and the sustained attack on the Safe Schools curriculum.

“the kind of queer activism she is identifying is just one component in a wider LGBTQ and gender/sexual diversity in Australia”

Secondly, Oriel’s concerns about the guidelines are grounded in a profound misunderstanding about LGBTIQ+ politics, inclusivity and diversity practices, and the realities of gender and sexuality today.

What guidelines of this sort can do is help journalists to help the public curtail hate speech, insult, ostracisation and the less obvious forms in which dignity is denied minorities, especially in terms of gender.

The new press guidelines, for example, provide valuable advice for journalists to help them avoid misgendering, or using pronouns that do not match an individual’s identity. Oriel may think it silly, she may feel that the gender assignment at birth is the only gender, or that people should get over being misgendered.

The reality, of course, is that the kind of queer activism she is identifying is just one component in a wider LGBTQ and gender/sexual diversity in Australia, an important part of the debate, and not separate from or at odds with the wider population. The critique of biological gender identity and the reality of transgender experience are closely related and, frankly, pretty well understood by a contemporary wider mainstream in Australia today.

“These are not dreamt-up follies of a radical queer politics threatening western civilisation”

One thing the Press Council is doing is playing catch-up with recent shifts in gender and sexual diversity, identity and new languages that have emerged over the past five years.

There are now—literally—hundreds of terms to describe gender and sexuality that go beyond the over-simplified and overly-exclusive masculine/feminine and hetero/homo dichotomies that we all recognise as having been always too simple to really capture the diverse, nuanced and complex ways in which we ‘do’ gender and sexuality in the twenty-first century.

These are not dreamt-up follies of a radical queer politics threatening western civilisation, but actually emerge from everyday young people looking for better ways to express the complex realities of gender and sexuality in the complex twenty-first century.

The very western civilisation which Oriel so strongly advocates and sees as being threatened by queer politics is one which actively respects and promotes diversity. It is therefore not only strange but naïve for her to denounce guidelines that foster good relations with diverse people as being a form of censorship.

What she fails to address in her simplistic rant, however, is that human rights frameworks need constant monitoring and criticism to ensure they are keeping up with the constant changes in belonging and marginalisation over time. Culture does not stay still but is fluid and changes over time. That includes LGBTQ culture which, thankfully, has continued to develop so that we can now articulate new ways of belonging and practising sexual and gender identity that are even more inclusive and respectful of the complex diversity of everyday lives.

Jennifer Oriel is an intelligent, educated person who does, indeed, engage with contemporary ideas, new norms of gender and sexuality, and complex issues of free speech and censorship. This is what makes it very hard for many of us to imagine that she actually believes what she is writing.

Rather, Oriel appears to be ‘getting off’ on causing trouble and riling up hatred against minorities by appealing to base ideas, simplistic views and creating fears that somehow diversity will take away the freedoms and luxuries enjoyed by the Australian majority.

Rob Cover is Professor of Digital Communication at RMIT University and the author of “Emergent Identities: New Sexualities, Genders and Relationships in a Digital Era.”

The original article by Jennifer Oriel can be found here: www.theaustralian.com.au/commentary/queer-how-press-council-would-suppress-the-truth