Queer content

The 2005 Sydney Film Festival opens with the lesbian-themed My Summer Of Love. But the festival’s new artistic director Lynden Barber won’t call it a queer film.

I don’t think it is a queer film with a capital Q -“ it has queer content but the lesbian nature of the relationship is accepted so naturally by the filmmaker and therefore by the audience that it never seems like a big issue.

Pawel Pawlikowski’s story -“ about two teenage girls from opposite sides of the track who form an intense and sexual connection during one hot English summer -“ was a huge critical hit in the UK, scoring BAFTA’s British Film of the Year award.

My Summer Of Love [pictured] is not so much about sexuality. It’s about teenage girls and how the connection you have at that time in life can be more intense than at any other time in your life. It can spill into a sexual relationship but need not.

The queer films in the Sydney Film Festival are there not because they are queer films, says Barber, but because they are great cinema that just happen to have gay or lesbian content. And because they can cross over to satisfy a general audience.

Barber sounds a little exhausted on the phone -“ a little talked out -“ but really the former Australian film writer couldn’t be happier now he is selecting the films for Sydney’s annual cinema orgy.

For starters, he has tried to broaden the scope and moods that the festival covers to include films for everybody -“ not just hardened cineastes.

Even the most dedicated cinephile doesn’t want to sit through four serious art-house films from eastern Europe, Barber says. If anything I’ve tried to add some more choices for serious cinephiles.

The festival’s classic fare is supplemented by several sub-programs, including selections for fans of music and sport, which will screen at the festival’s newest venue, the George Street cinemas.

Showcases highlighting some of the best films coming out of Britain, Argentina and Asia bump up against new independent cinema and works by visionary filmmakers including Werner Herzog, Greek maestro Theo Angelopoulos and queer filmmaker Gregg Araki, whose exquisite exploration of the impact of pedophilia on two boys is a festival highlight.

The adventure has kept Lynden Barber sitting in the dark for much of the year, globetrotting from festival to festival. The most exciting cinema on world screen right now? Documentary.

In fact, the word documentary hardly describes it -“ -˜non-fiction’ might be better, says Barber.

The most interesting works, he says, are the hybrid works such as Jabe Babe: A Heightened Life by Sydney filmmaker Janet Merewether, well regarded for her film title designs. Jabe Babe is a portrait of a woman born with the elongating and potentially fatal Marfan Syndrome.

Barber points also to Caveh Zahedi’s ?-subjective I Am A Sex Addict. Zahedi uses home movies, straight-to-camera address and reconstructions to explore his recovery from his addiction to prostitutes.

Another self-portrait is Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation. This documents the 31-year-old gay man’s entire life on videotape and film.

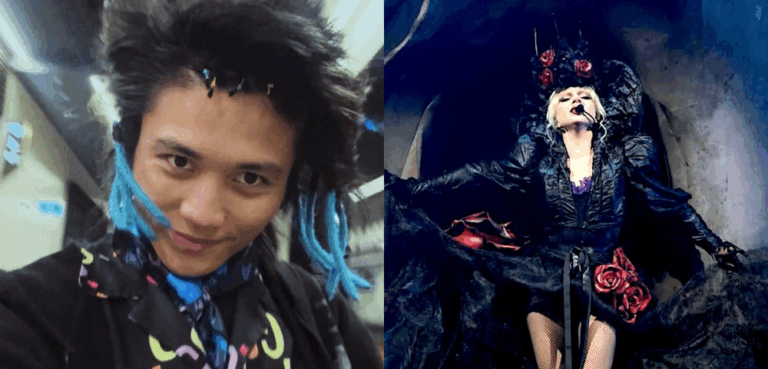

Tarnation blew everyone away at Cannes and the Sundance festival for its frank telling of Caouette’s fractured Texan upbringing, his mother’s chronic mental illness and the alternative gay culture he immersed himself in.

Lynden Barber describes Tarnation as a milestone film that reveals a new way of making a documentary or a home movie -“ which sounds amateurish but this has a virtuosic technique.

Barber says documentary and narrative films are beginning to borrow from each other’s techniques, citing Denmark’s Dogma filmmakers among the forerunners.

There’s an increasing use of first person where the filmmaker is part of the film. Michael Moore popularised that form but [documentary filmmakers] Nick Broomfield and Ross McElwee had done it before.

The subjective frame is in clear view in queer maverick director Gregg Araki’s drama Mysterious Skin and it marks a new maturity for Araki whose earlier films, including Totally F**ked Up, The Doom Generation and The Living End could be chaotically hit and miss.

Based on Scott Heim’s novel about two boys abused by their baseball coach, Araki brings in voice-over narration and some remarkable point-of-view filming techniques to give the cinema audience a child’s insight into the pervasive and continuing destructive nature of pedophilia.

Perhaps the queerest film in the 2005 program is the Argentinean winner of the Teddy award at the Berlin Film Festival for best queer film, A Year Without Love, about a young writer dealing with his newly positive status.

Looking to escape the loneliness that can follow seroconversion, Pablo falls into the local SM scene.

Last, but not least, on the festival’s queer menu is Ring Of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story.

Emile Griffith made boxing history on many occasions: six times as World Welterweight champion and once for pummelling a young Cuban boxer Billy Kid Paret to death in the ring. It was 1962 and Griffith never got over it.

What emerges in Ring Of Fire is that Emile Griffith, a gay man who was once a hat designer and remarkably gentle for a boxer, had exploded in anger over Paret’s homophobic taunting in the ring. He sent a vicious array of punches from which Billy Paret never recovered.

The Sydney Film Festival screens from 10 to 25 June at the State Theatre, Dendy Opera Quays, George Street Cinemas, Art Gallery of New South Wales and at The Studio, Sydney Opera House. There is an online festival guide at www.sydneyfilmfestival.org