Forty-one years ago a small group of demonstrators gathered in Sydney to protest the pre-selection of a conservative Liberal candidate, the first gay demonstration in Australia.

Six months later, George Duncan was drowned while cruising by Adelaide’s Torrens River, possibly by police, opening up a debate which would lead to South Australia becoming the first state to decriminalise homosexuality in 1975.

The lesbian and gay movement grew out of larger social changes of the time that saw radical shifts on how Australians imagined ourselves. The dramatic shifts in policies towards women, non-European migrants and Aborigines, to some extent a product of the Whitlam Government, opened up space for a new approach to homosexuality.

Political commentator George Megalogenis has spoken of the ways in which Australia was transformed in the past few decades by “wogs and women”. Homosexuals both benefitted from, and contributed to, the changes of which he writes.

This is not to argue that we have won total acceptance. Rather there is a strange balance between well-meaning acceptance and hostility that means we constantly need to negotiate our place in the larger society. Certainly the attitudes of 40 years ago, when homosexuality was defined as sick, deviant and criminal, have largely disappeared.

But rather than total acceptance of sexual diversity, this means an uneven pattern which is not always predictable.

We know from research carried out by the Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society that there remains a high rate of depression and psychological distress amongst queers (ARCHS speaks of “GLBT’ but I use the word to cover those who are either homosexual or transgendered).

We also know there is a high rate of harassment and experience of discrimination, with trans people particularly subject to abuse. But 6 percent of women surveyed and more than 10 percent of men reported violence or threats of violence, and such abuse continues despite changes in general attitudes.

These figures match experiences Toby Lea’s research has recorded amongst young queers. There are special issues for people in certain religious and ethnic communities, as the recent ACON report on gay Arab-Australians revealed.

As we argued in those lost days of gay liberation, legal reforms by themselves are inadequate to deal with the real roots of homophobic violence and prejudice, nor will reason itself be sufficient to eliminate hostility.

What has changed, and changed dramatically, is that most of us are open about our sexuality most of the time. “Coming out” was the most dramatic expression for the early gay movement of the personal as political, and over the years there has been a steady increase in public figures who are openly gay, including a number in high positions.

Yet ‘coming out’ remains a rite of passage that all those who differ from conventional sexual and gender norms have to negotiate. Unlike other forms of identity, being queer is almost always to break with one’s biological family: one rarely thinks of oneself as queer as part of one’s family heritage.

This explains why same-sex marriage is such a charged issue: it represents competing visions of what constitutes “family”. For many lesbians and gay men, acceptance of marriage is a symbolic way of re-entering their biological family as equal members.

The early gay movement came out of the left, and desperately wanted to be radical. This started to change in Australia as HIV required gay men to work with the state, but it is really with the marriage movement that homosexual activism has become professionalised and respectable.

These changes have taken place not only within Australia. Over the past several decades there has been an explosion of activity in many parts of the world as new groups, asserting various forms of ‘queer’ identity and community, emerge in countries where the space to be gay is remarkably restricted.

These groups would have emerged differently, and with less support, without the AIDS epidemic. The epidemic opened up discussion of sexuality, and funding for emerging groups across the world, and some of my best memories of 25 years of involvement in HIV come from working with emerging queer groups in other parts of the world.

I have met many brave women and men who literally risk their lives in fighting for basic freedoms across most of the world. The challenge is to find ways of supporting them that avoid charges of neo-colonialism, as were thrown at British prime minister David Cameron when he announced British development assistance would be cut where homosexuals were persecuted.

I would love to see some of the political savvy that has gone into the campaign for same-sex marriage directed at thinking through how we might develop support for a global lesbian and gay movement. We have a lot to learn from the people who are now reinventing ideas of liberation and sexual rights in countries like Kenya, Brazil and Indonesia.

By DENNIS ALTMAN

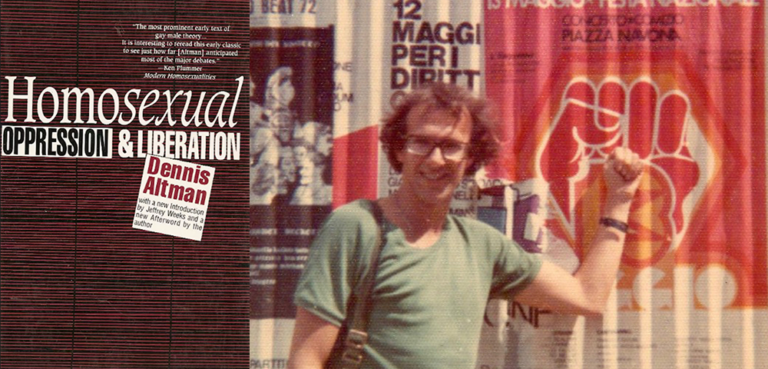

INFO: Dennis Altman is a gay rights activist and author of the 1971 book Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. He will appear at two Sydney Writers’ Festival events: ‘A look at Homosexual 40 years on’, at Sydney Theatre, 1pm, May 19, and ‘Why Get Married When You Could Be Happy?’ at Sydney Town Hall, 6pm, May 19. www.swf.org.au

PICTURED: Dennis Altman (far left) at a demonstration outside Liberal Party HQ in 1971. Photo: Phil Potter.

“For many lesbians and gay men, acceptance of marriage is a symbolic way of re-entering their biological family as equal members”

I think thats true for plenty of people, but I think Dave’s comment hits the nail on the head. Lots of people just see it as a straight forward issue of discrimination and find that unacceptable. While marriage rights won’t bring an end to some of the deeper issues you hint at, such as why queers have to come out, those issues can’t be resolved either while there are laws that plainly state queers are less than straight.

“strange balance between well-meaning acceptance and hostility..” has brought about situation where queers are still descriminated against, but also the largest protests and other political agitation by queer people, who are able to come out in the current climate.

Three cheers Dennis Altman!

We have certainly come a long way, and I take my hat off to the early LGBT Activists

I have read numerous books and journal articles over the years while a student at UNSW. Always enjoyed Mr Altman, and what he has to say.

Drew

“For many lesbians and gay men, acceptance of marriage is a symbolic way of re-entering their biological family as equal members.”

Interesting statement. But marriage is a hollow symbol if your biological family – not to mention other sectors of society – still don’t see you as equal.

Terrific article Dennis!

My friends son is 17 and Gay. My friend has three sons in all. Everyone brings their girlfriend or boyfriend around on the weekends, they are in a country town, and have a large extended family who accept and love my friends son, the same as his brothers. At his school he has some other same-sex attracted friends. I think this is a measurement of how far we have come, when teenagers can start to live as any other teenager. It is thanks to the efforts of people like you, who have been active in our Civil Rights struggles. Marriage is an interesting topic and at times challenging debate, but for people like my friends son and his brothers, they simply look at it as black and white discrimination, with no shades of grey.

The conservative David Cameron is years ahead of the Australian Liberal Party, with Tony Abbott trying to make it a Vatican outpost. The front bench is now dominated with far right Catholics, who seek a Nanny State on matters of equality.