“Locked out of my community”: How accessible are queer spaces?

Ayman Barbaresco was at an LGBTI networking event when flashing lights and loud music triggered a migraine.

“It was overwhelming,” he told the Star Observer. “It was impossible to focus or do anything.”

As a gay man with a disability – he has a neurological disorder and has battled two brain tumours – Ayman said he sometimes feels invisible in queer spaces and wishes more people would look past his disability.

“Our disability is only one aspect of us,” he said. “It doesn’t define us. We’re just normal people.”

In 2018, La Trobe University published a report about the difficulties faced by LGBTI people with disability, with 46 per cent experiencing discrimination, harassment or abuse in the past year.

The report found LGBTI people with disability also experience limited access to services, lack of sexual freedom and expression and reduced support and social connection with both the LGBTI and disability communities.

Some LGBTI venues have appealed to the community to help make their spaces more accessible. In 2013, Hares and Hyenas fundraised to install an accessible toilet, and in 2014 a microphone system for wheelchair-using performers.

Erin Kyan, a spoken-word performer who describes himself as a “disabled, fat, queer, trans, leather man”, told the Star Observer while queer spaces in Melbourne are often more inclusive than mainstream venues, they are “nowhere near fully accessible”.

“Queer venues that tend to be accessible are the more traditionally ‘wholesome’ ones, like cafes, or social support groups,” Kyan said.

“Pubs are less likely to be accessible, and club nights or sex-on-premises venues are pretty much never accessible. I think this is a symptom of a common belief that disabled people aren’t sexually expressive beings.”

Some of the ‘obvious’ steps event organisers can take to include people with disability are ensuring the venue is wheelchair accessible and Auslan interpreted, “but access doesn’t just stop there,” Kyan said.

“Is there enough seating at your event? Do you have a priority seating area? There are so many disabilities that make standing difficult and having a secure place to sit can make a huge difference.

“Is there smoking at your venue? Secondary smoke can be a real problem for some health conditions. How loud is your event? How bright are the lights? Both of those things can be problems for people with sensory issues.”

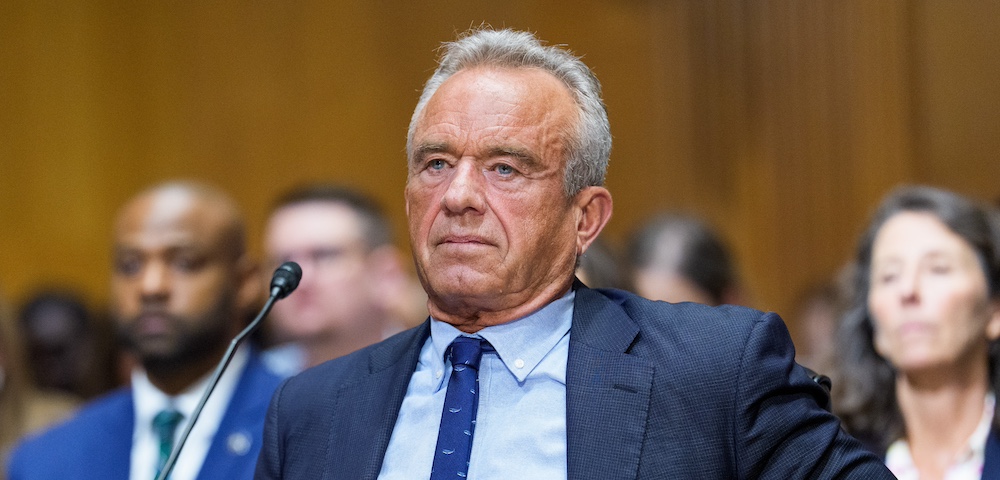

Ayman Barbaresco. Photo: supplied.

Erin said this information should be listed on event and venue websites and social media. If organisers are serious about including people with disabilities, he said they should seek out disabled “performers, speakers, staff [and] consultants”.

“Disabled people aren’t always just attendees or customers. We deserve to have our chance to be on stage, in the spotlight, as much as abled people,” Kyan said.

“Hire a disabled DJ, showcase a disabled drag performer, give a disabled poet a slot, let a disabled person facilitate trivia … including us means including us in all aspects of community.”

Barbaresco agrees queer venues need to “ask people with disability what they need” and must realise “everyone is different”.

In recent years, LGBTI people with disability have advocated for greater visibility and recognition. More than 150 LGBTI people with disability – a record number – marched in the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade in 2017. Earlier this year, LGBTI people with disability participated in a Mardi Gras float, the Fearless Express, to raise awareness about public transport accessibility.

Without accessible queer venues and events, Erin said he and other LGBTI people with disability are unable to interact with the rest of the LGBTI community.

“Things like my powerchair make it possible for me to be a part of society, which is why it’s so important for queer spaces to be accessible,” Kyan said.

“Without that accessibility, I am locked out of my community entirely. We need our community, and the community needs its disabled members.

“We can bring a lot to the table if you let us.”

Matty, if you’re worried about how the disabled people get out, then that’s part of being accessible. You think about it beforehand and plan for it.

If you’re worried about, ‘Ooh, we’ll all trip over their wheelchairs,’ then make sure you’re using the correct exit and you wont have to worry.

This is a great article with very good points and interviews. ???????? And I find it’s true too, that rainbow events and organisations do seem to be more proactive in making better access for the disabled.

Additionally, I’m a member of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Choir (I first started in 1992). Our choir’s always had a sincere priority and policy to be inclusive of *everyone* since it started in 1991 (one of many aspects that attracted me into joining in the first instance), and since I came back as a chorister in March after six years’ absence with my own mobility disability, I’ve been definitely experiencing that genuine inclusivity – and there’s never a feeling of being an ‘other’ whatsoever. ????

They have been so marvelous; I’ve had assistance – both physically, and through correspondence assistance with an organisation to sort out a problem with venue accessibility).

There’s always a complete and genuine sense of being at one with the choir that buoys me to feel far more abled (plus, I feel in a far better state of mind: emotionally and psychologically since I’ve been back). And I know others with various concerns in their life who also gain much from the choir’s inclusivity.

So I just wish to say a magestic and public thank you to a great Rainbow group: the SGLC ????✨????????️????????

One good service that I’ve discovered for the disabled, that I’d highly recommend, is a not-for-profit organisation called ‘Touching Base’ (a group, I think, that should be covered in a future Star Observer issue).

I heard about them years ago on ABC TV’s ‘7.30’.

Many months after I became disabled in more recent times, I thought I’d contact them.

The group is run by volunteer sex-workers, and two of its patrons are Justice Michael Kirby and Eva Cox.

The organisation is a place were sex workers can register to offer services to the disabled, and some of them also offer services for our Rainbow Community ????????️????????

They’re given good training in many areas, like understanding and learning to empthise (if they’re not sure beforehand), etc.

I’ve never had the services of a sex worker before, but it was completely and truly wonderful, not only for the ‘obvious’ but the yum gent I encountered was so genuine in his friendliness, in discussions and chats, and so forth.

But not only that, his wonderful holistic approach left me feeling overarchingly confident in myself (and not just sexually) so it was a truly and completely therapeutic experience for me. And still, months later, the overall confidence I gained from that one time (I can’t afford to do this as much as I’d love to ????) has carried through into my daily life through to today. And I am definitely thankful for ‘touching base’ and that gorgeous magnificent gent, for lifting my confidence (to much higher than it was before my disability), ????????☀️????

If only those blinkered individuals behind the funding of the NDIS would get their heads out of the sand (and out of the gutter) to realise how good sex is holistically: on an emotional, psychological and confidence-building level, not just for ‘down there’ moments.

Here’s a link to ‘Touching Base’, who can refer disabled people to their catalogue of approved sex workers …

https://www.touchingbase.org/

Sometimes you have to think … What would happen if there was a fire in the nightclub that night?