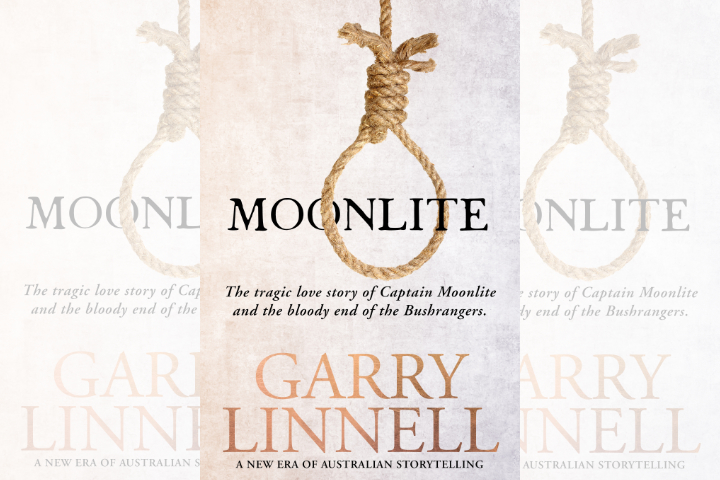

Moonlite

It is the evening of January 19, 1880. In just a few hours the New South Wales executioner Robert ‘Nosey Bob’ Howard will place a noose around the neck of the man known as Captain Moonlite – the most charismatic and controversial of all Australia’s bushrangers.

His real name is Andrew George Scott. Born into privilege in Northern Ireland, he has been a sailor, soldier, engineer and preacher. But in 1879 he and his lover, James Nesbitt, along with several other young men, laid siege to the Wantabadgery Station near Gundagai.

Nesbitt died in the subsequent shootout, along with a police officer. In this extract from the newly released non-fiction book Moonlite, we join Captain Moonlite in his death cell in Darlinghurst Gaol as he prepares to face the gallows.

Back in November when the siege near Wantabadgery station had finally reached its horrible conclusion, the police found Scott slumped over Jim Nesbitt’s body, crying and kissing the young man’s slack, blood-smeared face, as though his breath and grief might somehow conspire to bring him back to life.

When they finally hauled Scott to his feet, handcuffed him and led him away, Scott took with him a lock of Nesbitt’s hair. In the years to come, as legend and myth and fact all merged into one, it would be said that Captain Moonlite went to the gallows with that lock of hair forming a ring on the wedding finger of his left hand.

But Scott is now prepared to surrender the last physical reminder he has of James Nesbitt. He no longer has any need to cling to the hair because soon he is going to join the man he loved like no other. He will have all of him, again.

So Scott takes up his fountain pen, dips it into what is left in the inkwell, and writes to Jim Nesbitt’s mother on one of the last sheets of blue prison paper he has been given. She is a woman who has known more pain than most. The only peace she seems to enjoy these days are the weeks and occasional months when her vicious husband is sent away for one of his regular stints in prison.

“My dearest Mrs Nesbitt,” writes Scott. “To the Mother of Jim, no colder address would be true. My heart to you is the same as to my own dearest Mother. Jim’s sisters are my sisters, his friends my friends, his hopes were my hopes, his grave will be my resting place and I trust I may be worthy to be with him where we shall all meet to part no more, when an all-seeing God who can read all hearts will be the Judge. When intentions will be known and judged of.

“As to my dearest Jim I have felt that the love and friendship – true, pure, real friendship that blessed our union – demands that I should defend his name to the last. My efforts are but weak, yet in time it will be known that he was an honour to all connected with him.”

Scott pauses and reaches into his prodigious memory, searching for better words that might tell Mrs Nesbitt just how strongly he felt for her son. He has always loved poetry. Others have always marveled at his ability to summon passages from even obscure works. Raised in a small town in Northern Ireland by a well-off family that lived in a manor, nothing had been spared when it came to young Scott’s education. He had devoured all the Classics and immersed himself in the poets of the Romantic Age, startled at how their words and rhythms could touch and move a person’s soul.

Now he recalls a verse from ‘The Lady of Provence’, an elegiac lament by the English poet Felicia Hemans about a lost lover. He begins writing again.

“I have won thy fame from the breath of wrong;

My soul hath risen for thy glory strong;

Now call me hence by thy side to be;

The world thou leav’st has no place for me.

Give me my home on thy noble heart.

Well have we loved – let us both depart.”

“These lines speak from and to my heart,” Scott explains. “I know that before long his memory will be blessed, and his bright example pointed to. I will not be long before I am with him and in his grave. Mrs Nesbitt, mother of my Jim, may the great God enable you to bear the great loss you have suffered.”

Before he signs off, Scott takes the lock of Nesbitt’s hair and places it on the page. “I send you some of his hair and will try to send you anything else I can get…farewell my dearest Mrs Nesbitt. I am ever to you a loving son in spirit. A. G. Scott.”

And with that, the long work of the man they call Captain Moonlite is all but over. Soon the sun will rise. Come now, let us leave him to rest, to lie on his hammock, to say his prayers to a God he is no longer sure exists, to remember the good times and hope, like everyone else, that Nosey Bob has paid attention to all the little details.

Robert Howard, a man who also remembers what it was to love and be loved, to hold and be held, has an important job ahead.

He must carry out the orders of the court and the government and obey the wishes of the people.

But most of all, Andrew George Scott is counting on Nosey Bob to send him back to the loving arms of James Nesbitt.

This is an edited extract from Moonlite by Garry Linnell, published by Michael Joseph, RRP $34.99, available now.