Tasmania’s transformation from worst to best

Rodney Croome share lessons with Star Observer about how to make positive change highlighted by “The Campaign” by Campion Decent

As audiences in Sydney and Melbourne enjoy Campion Decent’s masterful play about the gay law reform campaign in Tasmania, it’s timely to mull over some of the lessons from Tasmania’s transformation on LGBTIQ equality and their relevance to today’s struggles.

First, let’s lay out the magnitude of the Tasmanian accomplishment.

- In 1988, Tasmania had the worst laws, policies and attitudes on LGBTIQ people in Australia.

- Homosexuality was punishable by 21 years gaol, and cross-dressing by steep fines.

- Gay law reform advocates were arrested for having a petition in a public market.

- Angry anti-gay rallies were held across the state.

- Support for decriminalisation was only 30% – well below the national average.

I still vividly recall the first gay community I attended where I was warned the police could be outside taking down the car registration numbers of people leaving the meeting to add to their “pink list” of known homosexuals.

Today, the picture couldn’t be more different.

Tasmania has the nation’s strongest LGBTIQ discrimination and hate speech laws. There are no exemptions allowing discrimination against LGBTIQ people by religious organisations.

All forms of hate speech, humiliation and intimidation are prohibited, without a religious exemption, which is why the Morrison Government wants to directly override our legislation as part of its Religious Discrimination Bill.

We also have Australia’s strongest laws recognising LGBTIQ relationships, expunging LGBTIQ criminal records, and ensuring equality for transgender and gender diverse people.

These laws are so strong they compare favourably with any in the world.

The same goes for government policy: Tasmania’s premier was the first in Australia to commit to apologising for historic discrimination, many schools are taking up LGBTIQ inclusion programs, and the Tasmania Police Service has become a model for LGBTIQ inclusion around the world.

And don’t forget we helped lead the nation on marriage equality with Australia’s first state same-sex marriage law and first successful parliamentary motions.

Just as remarkable is the shift in community attitudes that underlies these legal and policy reforms.

In the postal survey, Tasmania returned a Yes vote higher than the national average and equal second among the states.

This was despite Tasmania having the oldest, poorest, most rural and least educated population; factors which some people think correlate with anti-LGBTIQ prejudice but clearly don’t.

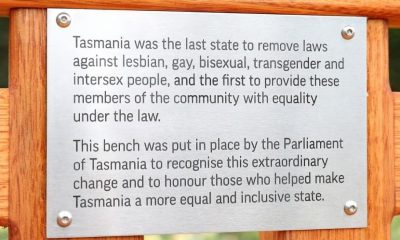

Tasmanians are proud of our island’s transformation and have celebrated it with a public artwork in Salamanca Place, a special equality chair in Parliament Gardens and an LGBTIQ equality plaque and tree in Ulverstone where the worst of the anti-gay rallies were held.

On every measure of inclusion, Tasmania can rightfully call itself the Rainbow Isle.

So how did Tasmania go from worst to best?

We took risks.

Whether it was taking an unprecedented complaint to the UN, conducting vigils outside angry hate rallies, or admitting illegal sexual activity to the police, we didn’t listen to those who advised us “now isn’t the right time or Tasmania the right place”.

We knew the situation required us to take a stand and that is what we did.

Another key to Tasmania’s success is that we didn’t settle for second best.

Perhaps it was because we were confident history was on our side; perhaps it was because we had to fight so hard; perhaps it was because in a mountainous land like Tasmania you understand the rewards of climbing to the very top; whatever the reason, we said ‘No’ to every compromise.

The result was the least caveated LGBTIQ laws in the nation.

Personal stories also had a big impact, especially in a place as interconnected as Tasmania.

We developed our personal story-telling skills in workshops and then told those stories at Rotary Clubs, CWAs, party branch meetings and to whomever else would listen.

That brings me to the final key to change: a sense of place.

The personal stories we told were about discrimination in school and at work, rejection by family and friends, fear of the law and of government; but beyond all this our stories were about wanting to be part of the island society that had shaped who we were.

This strong sense of place, this overwhelming desire to belong, gave our cause a resonance with other Tasmanians that it was impossible to ignore.

To today’s advocates struggling against the movement for religious privilege, for the dignity of trans folk, and for the banning of conversion practices, I recommend the approach we Tasmanians took.

Don’t listen to the voices of caution, don’t do deals on your rights, have faith in your fellow citizens and reach out to them.

Most of all, ground everything you do in the unshakable belief that you belong in whatever community or place that has made you who you are.

________________________

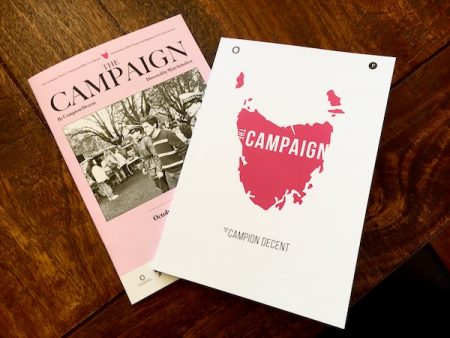

The Campaign, by Campion Decent, depicts the struggle and ultimate success by Rodney Croome and fellow campaigners to change Tasmania’s anti-gay laws.

It is playing at Sydney’s Seymour Centre as part of Mardi Gras from Feb 11 – 28. Click here for details.

For a preview of the play and a discussion with Campion Decent, click here: Historical Tasmanian Campaign Unfolds On-Stage