How the ‘gay, Indigenous, resistant’ Guatemalan film José came together

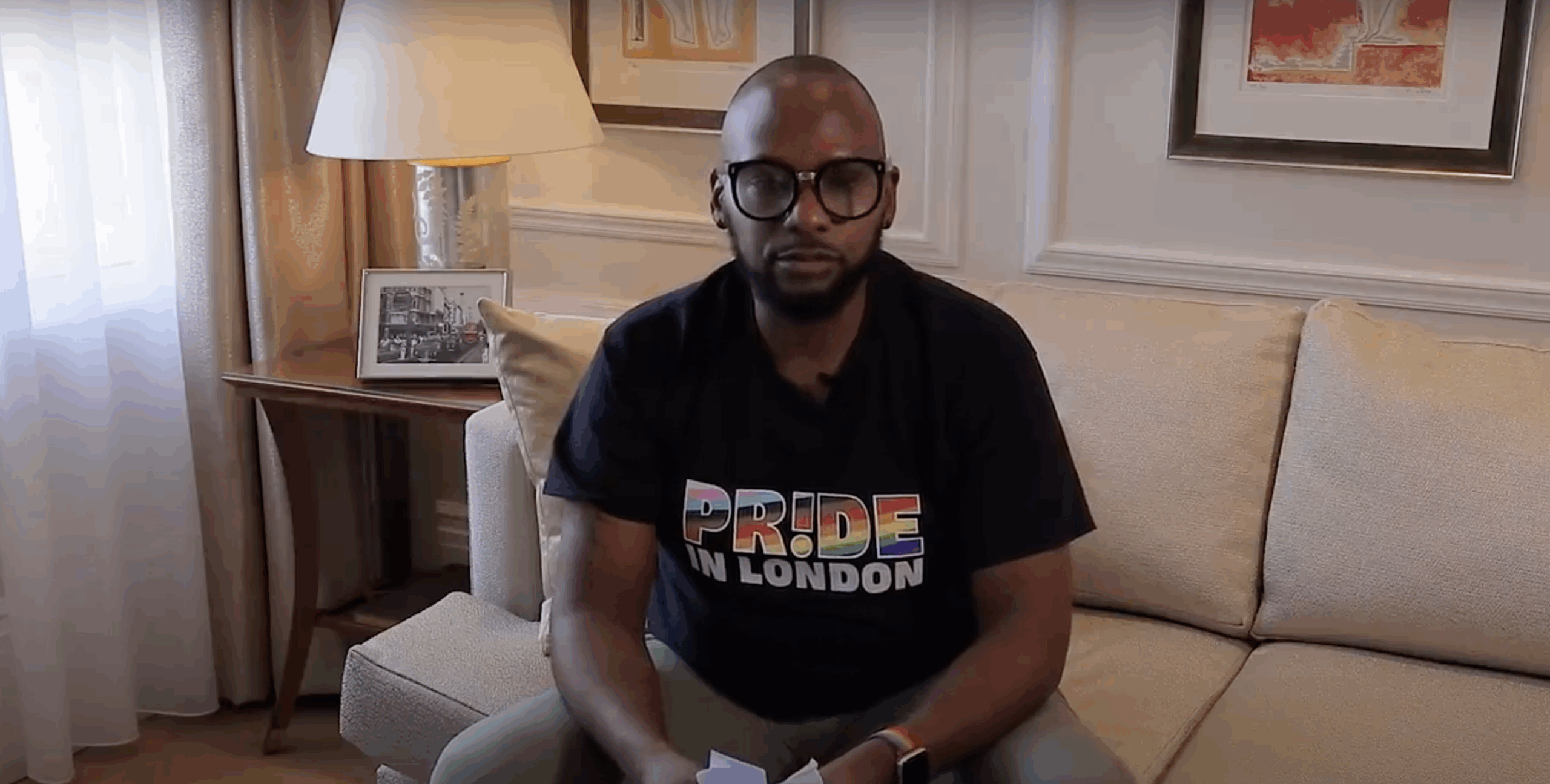

José recently won Venice Film Festival’s Queer Lion award, and soon plays the Mardi Gras Film Festival. Director Li Cheng and producer George F Robson sat down with Robert McGrath for their first extended interview.

* * *

On first take, José is an gay love story set in teeming Guatemala City—novel enough.

However, as José unfolds, it reveals more about the lived experiences of millions in Latin America.

Metaphorically, José is located in the middle of the swirling confluences currently coursing their way through the hemisphere.

José’s world is impacted by drug cartels and criminal gangs; limited opportunities and hyper competition; corruption and ineffectual administrations; overcrowding and chaotic urbanisation.

Any wonder there are human caravans heading to walls that don’t exist, while devotional religion maintains its reassuring grip on the popular imagination—if only to make the unbearable bearable.

As producer of the film, George F Robson knows too well.

“Realities are made harsher by being poor, non-white, and gay… and having few opportunities,” he says.

“Finding a love relationship amongst all that, can be an impossible dream.”

The story itself is fiction. It’s an amalgam of personal stories collected by George and director Li Cheng from interviews with young people across twenty of Latin America’s largest cities.

Robson and Cheng consistently sought answers to three essential questions: Who are you closest to in your life? What is your most unforgettable memory? Have you been in love?

The individual vignettes they sourced flowed into their representative, fictionalised screenplay.

The film was realised with a fully Guatemalan production crew and features first time actors Enrique Salanic and Manolo Herrera.

The story follows two young men as they stumble, almost inadvertently, into love.

As their relationship progresses, they are buffeted by the social, economic, and religious imperatives in their lives.

The simplicity of the relationship is the quiet centre of their complex world.

The story unfolds with a subtle observer’s eye. Its film language draws on the post-war, Italian neo-realists, and particularly the work of murdered gay director, Pier Paolo Pasolini.

His films presented dignifying visions of ordinary people.

“Pasolini is definitely at work in José…” Robson says.

“He was ahead of the curve.”

If José was set around a languidly dappled pool, forsaken in the fading light of a failing Tuscan summer, it might be a heartwarming coming-of-age, gay love story.

But José is real; achingly real.

It hovers close to the documental, sifting through the layers and complexities of everyday life.

In teeming Guatemala City, sidewalks are a luxury, and muggings and the occasional little earthquake are unremarkable. Surely this is cinéma-vérité.

José also intrudes deeply and somewhat uncomfortably into the very personal. Yet it’s an appropriate treatment, given the lack of truly private space.

But, beyond the focused lens broils a darkening macrocosm that gives José its contextual texture.

In not so-far-away Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro must rank as the most threatening, foul-mouthed “leader” in the world today—and he has some competition.

As President, his once-ignored rants, must now be considered as state-sanctioned hate speech.

He has famously said he would “…rather have a son who is an addict than a son who is gay” and that he is “proud to be homophobic”.

He sees the Amazon Basin as “a child with chickenpox… every dot you see is an Indigenous reservation”.

But Brazil is a huge and diverse society, with a history of mass movements, ready to defend the rights of women, Indigenous people, and sexual minorities.

Around them, a nascent ‘resistance’ appears to be coalescing.

Immediately after Venice, José featured at the continent’s largest film festival, in the sprawling megalopolis of Sao Paulo.

There, the imperceptible intricacies and stoic forbearances of the film’s gay and Indigenous subjects seemed to confound the blabberous barbs of any Balsonaro-fueled bigotries.

After its showing, the film site, Artecines, splashed the headline, “José: O amor em forma de resistencia” (or “Jose: love as form of resistance”).

Meanwhile, following José’s success in Venice, Guatemala’s relatively liberal national newspaper, Prensa Libre, ran a double-page story with the headline, “José es una carta de amor para el país”; (or “José is a love letter to the country”).

However, José is yet to come out in Guatemala.

“There is concern for the safety of the actors,” Cheng explains.

Guatemala’s systemic and institutional problems are ongoing. The government recently expelled a UN-backed anti-corruption commission, just as it began digging too close to the President and his family.

Can José be part of a resistance in Guatemala?

Cheng’s thoughts? “I hope so”.

José will screen at the Melbourne Queer Film Festival on Sunday 17 March. For tickets visit: mqff.com.au/program/jose