The Road to Melbourne Pride

Peter McEwan has never forgotten the intense terror and utter shame he felt as a 17-year-old, when his father came to bail him out of jail in 1967.

McEwan, then a student at a Catholic all-boys school, had been arrested after the police caught him with a 22-year-old man in the bushes near Brighton beach, known to be frequented by gay men.

Coerced by Police into Confessing to ‘Homosexual Offences’

McEwan was convicted of homosexual offences on the basis of a statement coerced from him by police at the time of his arrest. He then endured two court appearances, psychiatric assessments and the real prospect of being sent to a youth detention centre. Finally, he was given a two-year good behaviour bond. That was not the end of his humiliation though, as he found his name and address along with those of other arrested gay men on the front page of Truth newspaper.

Victoria scrapped the laws used to target LGBT people in 1981. On February 13, the Victorian government will organise Melbourne Pride – a one-day street party to commemorate the 40th anniversary of decriminalisation of gay male sex in the State.

Laws Ruined the Lives of Generations of LGBT People

The road to Pride is, however, paved with stories like McEwan’s, whose conviction remained on the records till 2015, when the Victorian Parliament enacted bipartisan legislation to expunge criminal records due to historical gay sex charges.

McEwan told Star Observer that the laws against homosexual offences ruined the lives of generations of LGBTQI people.

“Having laws like that meant that society basically said that you were bad. It meant that you could get bashed on the street. If you reported it to the police, they could instead charge you if they found out you were gay. It meant the corrupt police could round up gay people, raid bars – the force of state was actively oppressing you,” said McEwan.

“It also sent a message to the society that it was okay to go out, hunt down, and bash gay people. You could be discriminated against at work. You could not be your true self and end up in freezing public toilets, where the police would lay traps for you,” said McEwan, adding, “many lives were ruined.”

McEwan went on to become a gay rights activist in the 1970s at university and then had a successful career in town planning. In 2016, when Premier Daniel Andrews issued a historic Parliamentary apology to the LGBTQI community, he agreed to become one of the public faces of survivors.

Gay Men were Not the Only Victims of Homophobic Law Enforcement

According to historian Graham Willett, it was not just gay men who were victims of homophobic law enforcement.

“Sex between women had never been illegal (and NOT because of Queen Victoria) but we do have a tiny little fragment of evidence that two women might have been charged with offensive behaviour for holding hands on a tram in the late 1970s or early 1980s,” said Willett.

“Trans people could be harassed for ‘offensive behaviour’ (wearing clothes not intended for their biological sex) but those in the entertainment industry seem to have come to an arrangement with the police that protected them,” said Willett.

Attractive Officers Sent to Popular Gay Beats to ‘Entrap’ Gay Men

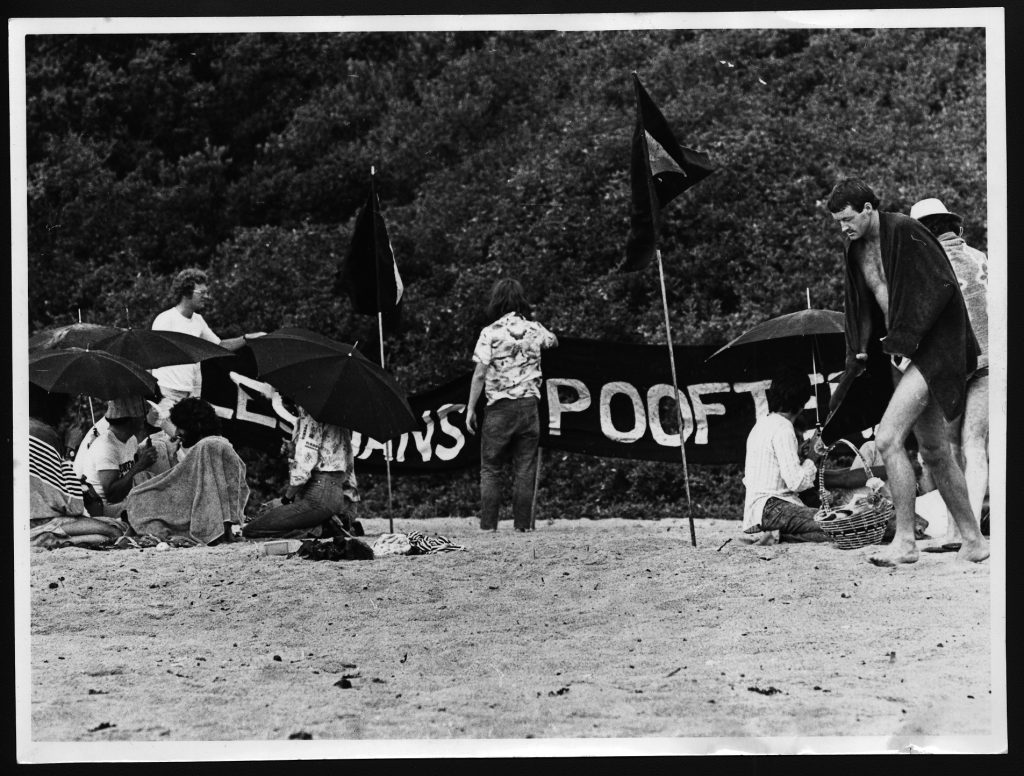

By the 1970s, though the law was not used very often, the threat of the law remained. In 1976, The Age reported under the headline Police Go Gay To Lure Homosexuals that around 68 men had been arrested for soliciting with homosexual intent.

Police revealed their modus operandi – some of the attractive officers would be sent to popular gay beats, like Black Rock Beach, to “entrap” gay men. Other officers would lurk around waiting to make arrests and then threaten the men to extract confessions.

The reporting of the police tactics led to public outrage. A year before this incident, in 1975, Jamie Gardiner and other activists had established the Homosexual Law Reform Coalition to lobby for change.

“[The law] was always in the background, a sword of Damocles over our heads,” Gardiner told Star Observer. “Our illegal status made organising hard, made gay bars unsafe and subject to police harassment. It created or validated prejudice and discrimination towards gay men (and lesbians as well by association).”

According to Willett, the 1980–81 reforms were hailed as the “best in the English-speaking world.”

“All sexual acts were treated alike – those between men, between women, and between other-sex couples. It introduced an equal age of consent and built-in protections for teenagers engaging in sex with each other,” explained Willett.

40th Anniversary a Time to Look Back and Celebrate – but Carry on the Fight

For LGBTQI advocates, the 40th anniversary of “homosexual law reform” in Victoria is a time to look back and celebrate, but also to carry on the fight for an equal Australia.

“One might have hoped decriminalisation would fix things, but of course it isn’t so simple. Decriminalisation certainly enabled changes to begin, but ending the prejudice, prohibiting discrimination, recognising and protecting our relationships: all these took hard work and came slowly: much is still be done,” said Gardiner.

“A lot of people think that the struggle is over, but there are still pockets in Melbourne and across Australia where young people are brought up with the message that they are not ok. They are inculcated with seeds of shame that can cripple their lives. Across the world LGBTQI people are killed for wanting to be their true selves,” said McEwan, who until recently was a Board member of the Victorian Pride Centre.

Star Observer’s Midsumma fg (Festival Guide)