More front than Myers

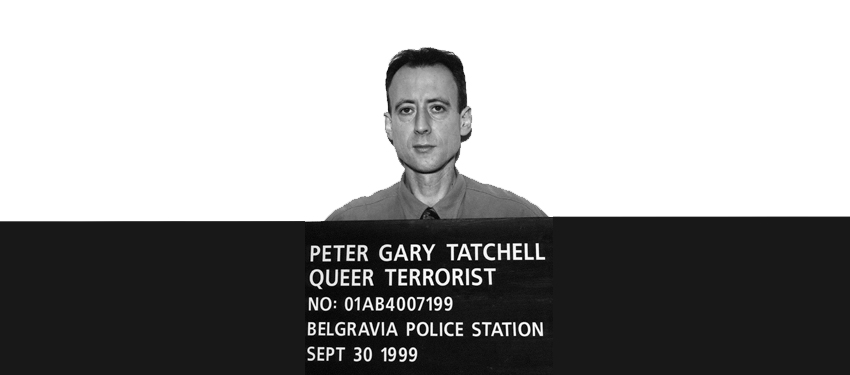

THE man once labelled a “homosexual terrorist” by the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper passes me a seat and a glass of water.

It’s difficult to know where to put either. So cramped is Peter Tatchell’s housing commission flat, full of ephemera from more than four decades of campaigning for LGBTI and human rights.

A garage he rents, which he used to store his archive, was burgled. So, he’s decided to temporarily store all of its contents in his tiny four-roomed home located close to south London’s traffic-soaked Elephant and Castle roundabout.

I find a space to sit between the mantelpiece, upon which sits a copy of a police mug-shot style portrait of Tatchell by Australian photographer Polly Borland, and piles of placards, including one of Vladimir Putin, the lips and eyes jauntily coloured in to give a more feminine air to the Russian president.

Born in the industrial Melbourne suburb of Footscray in 1952, Tatchell undoubtedly looks trim and younger than his 62 years despite referring to various ailments he is suffering from. His secret to avoiding that pesky middle aged spread? A regimen averaging one protest march a week — that’s around 3000 since he was 15.

His campaign group, The Peter Tatchell Foundation, has just announced plans to bring back his signature battle tactic — that of outing establishment figures who hide their homosexuality while espousing homophobia. A closeted MP voting against LGBTI law reform, for instance.

The trigger is the Church of England’s opposition to gay clergy marrying.

“But I’d say it will probably focus on any bishops who’ve supported anti-gay policies. The Church are moving very slowly,” Tatchell says.

It was this action, originally performed in the 1990s when he was a member of UK campaign group OutRage!, that made a Tatchell infamous. He became a target for the UK press, called a “prize pervert” and “public enemy number one” by Fleet St’s finest.

All that changed in 2001 when he confronted Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe, accusing him of torturing his own people. In a case, perhaps, of my enemy’s enemy is my friend, the Daily Mail hailed him as a hero. By 2009, the same paper was openly asking if Tatchell was “the bravest man in Britain”.

While the phalanx of tactics — from pub sit-ins to pulpit invasions — have proved controversial, Tatchell has nonetheless been at the forefront of debate on LGBTI issues from equalising the age of consent to same-sex marriage and a multitude of other global human rights abuses.

“What I admire most is that Peter’s actions are an equal mix of bold courage and peaceful non-resistance,” Australian Marriage Equality national director Rodney Croome says.

“In 50 years’ time, when much that Peter campaigns for is accepted, he will be looked back on as a great hero of freedom and will be elevated to the company of Thomas Paine, Emily Pankhurst and Rosa Parkes.”

It’s a comparison Tatchell would smile at with many of his direct action methods having been adapted from the Suffragettes and the African-American civil rights movement.

Tatchell’s great grandfather was the first of the family to arrive in Australia. A cabin boy on a merchant ship, he jumped ashore and fled to the Victorian goldfields. He found not a single nugget. It was a similar experience on his grandmother’s side of the family.

“I’ve never been looking for gold,” jokes Tatchell, who claims he lives on around $18,000 a year.

“I know from family experience it will never come to anything.”

Tatchell’s father, a lathe operator, and his mother, who worked at the Brockhoff biscuit factory, split when he was four.

He eventually ended up in the semi-rural surroundings of Mount Waverley in Melbourne’s east with his mother, stepfather and three half brothers and sisters.

“We had a forest at the end of the road which was great for playing. The garden was dug up for fruit and vegetables and we had a big chicken coop where we kept about a dozen hens,” he recalls.

Despite occasionally being called “poofter Pete,” Tatchell remembers school as a time with fulsome friendships and the success of being elected as head boy.

“It was popularly alleged I had the best legs in school. I used to get wolf whistles,” he smiles.

“Mostly from the boys.”

Tatchell was just 11 when his sense of injustice began to surface after hearing about the bombing of an African-American church in Alabama that killed four young girls his own age.

By 15, he was actively involved in the campaign to pardon Ronald Ryan who was accused of shooting dead a warder from Melbourne’s Pentridge prison. The campaign was unsuccessful and Ryan became the last man to be executed in Australia. Tatchell says the result “destroyed my trust and confidence in the government, the police, and the courts”.

It wasn’t a popular view in Tatchell’s deeply-religious household.

“My stepfather said that the powers that be are ordained by God therefore you should obey the law and not question it, to which I said ‘was Adolf Hitler ordained by God?’” he recalls.

His stepfather’s reaction to a young Tatchell standing up to him? “Smack,” he says, “Punch in the face. My stepfather was brutal.”

However, he says the cruelty meted out by his stepfather put into perspective the insults received from passers-by when he protested.

Leaving school at 16, Tatchell found work at the now-defunct Walton’s department store on Bourke St in Melbourne CBD, and later at Myer, in the design department including dressing the famous Christmas displays.

“It was the closest I could get to an artistic profession without any qualifications. I helped create the tableau, costume the figurines and the scenery,” he says.

It was a skill he says influenced his later “visual and theatrical” protests.

In 1960s Melbourne Tatchell recalled that there were “two rather seedy gay bars and that was it”. He said it was at the department stores that he first met gay people, including his first boyfriend.

However, his protestations for his colleagues to join his nascent gay rights campaigns fell on deaf ears.

“They were all too scared. They said ‘you’re going to get us all arrested, you’re only 17, what do you know?’” Tatchell says.

So his attention turned towards other causes, such as encouraging young Australian men to refuse the Vietnam War draft.

A favourite spot to protest was at the imposing Melbourne GPO building which stood on federal land.

“Providing we gave out leaflets on the steps, not on the street, the state police couldn’t arrest us,” he recalls.

“They tried going up the steps and grabbing people but our people knew the law.

“But every Saturday we were living in fear that the Commonwealth police would turn up and then we would be done.”

While Tatchell is adamant he would have happily gone to jail to avoid the draft. But with the government seemingly unwilling to imprison scores of young men, he decided to head to London instead.

Aged just 19, it was a revelation.

“In Melbourne, I’d been a lone operator. In London, the meetings of the Gay Liberation Front had 500 people,” he says.

“It was so exciting, we were challenging the homophobia and transphobia not just of generations but millennia and that simple slogan ‘gay is good’ was revolutionary because it turned on its head the view that homosexuality was mad, sad and bad.”

Tatchell’s tactics have often brought him into conflict with other gay rights organisations with more sedate campaigning methods.

“So many people in the LGBTI movement are nowadays paid professionals, they go from one conference to another and many of them have lost their fire,” he says.

“You need people working inside the system but you also need radicals on the outside to shake things up.”

NSW Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby convenor Justin Koonin acknowledges that Tatchell has done “more than almost anyone” to bring LGBTI issues to public attention, but he is diplomatic about the methods used.

“There are advocates who work within the political system, those who work outside of it, and those who have done both,” he says.

“That is a good thing, and we ought to recognise the contributions that each other make.”

Does Tatchell think a campaign to out MPs or bishops would work in Australia?

“Yes,” he says, eyes widening, “it’s queer self-defence. We’re not attacking them because they’re in the closet, it’s because they’re hypocrites and homophobes.

“It’s hugely disappointing for me to see a country like Australia, with a very proud and long radical tradition, being so conservative on same-sex marriage.”

Much of the blame he lays on Prime Minister Tony Abbott who Tatchell strongly criticises, calling him “a man that hasn’t got a heart and has barely got a brain”.

He doesn’t stop there: “There’s every moral justification to make his life hell. He stands for discrimination, he’s a homophobe and I want to see him shamed, humiliated and embarrassed at every turn.

“I think to myself, why are Australian LGBTIs and their straight allies putting up with it? Why are they allowing him to get away with it?”

Croome, one of a number of Australian campaigners Tatchell rates highly, disagrees. He says direct action has occurred in Australia: “It has worked, many times. It’s just not as widely acknowledged because it’s not associated with the charisma of a figure like Peter.”

Croome adds that he has never supported outing, but he admires Tatchell’s “immense bravery in confronting the haters” directly.

“Peter pitches his appeals to the idealism, hope and compassion within the hearts of ordinary people,” he says.

“He figures once the community is onside politicians will follow, and he is generally right.”

Despite this, charisma can only get you so far. Tatchell’s consistent call for UK age of consent laws to be reviewed continues to lead to criticism. He is unbowed: “I’m not in the business of courting popularity. I’m doing the best I can to defend human rights and in my view even people aged under 16 have human rights.”

After more than 40 years of campaigning, Tatchell says he has “dragged” the prevailing consensus towards him.

“Throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s I was regularly attacked on the street which was symptomatic of the wider homophobia,” he says.

“The support I now have is symptomatic of the change in public attitudes.”

Might that consensus lead all the way to Buckingham Palace?

“I’ve been sounded out about a knighthood,” he reveals.

“I said no. Bowing down in front of the Queen as she puts the sword on your shoulders? It’s medieval and should be swept away.”

A seat in the House of Lords, perhaps?

“It’s slightly less worse. At least you can do practical things,” Tatchell says.

His radicalism, he says, is rooted in his early political experiences in Melbourne, but his direct approach has been fraught with risks.

“I’ve been violently attacked over 300 times, had 50 bricks through my windows, three arson attempts and a bullet through the front door,” Tatchell says.

“I’ve got brain and eye damage from the beatings by President Mugabe’s thugs in 2001 and again from neo-Nazis in Moscow in 2007.

“What keeps me going? I’m an unreconstructed Australian idealist — I’ve got an eternal optimism that things can and will get better.

“I’ve seen it in my own lifetime.”

**This article first appeared in the October issue of the Star Observer. The November issue will hit the streets on Thursday, October 16. Click here to find out where you can grab your free copy in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, Canberra and select regional areas.