New study kicks off program to tackle homophobic language in sport

A new Monash University study has explored the use of homophobic language in sport and the capacity of education programs to reduce its prevalence.

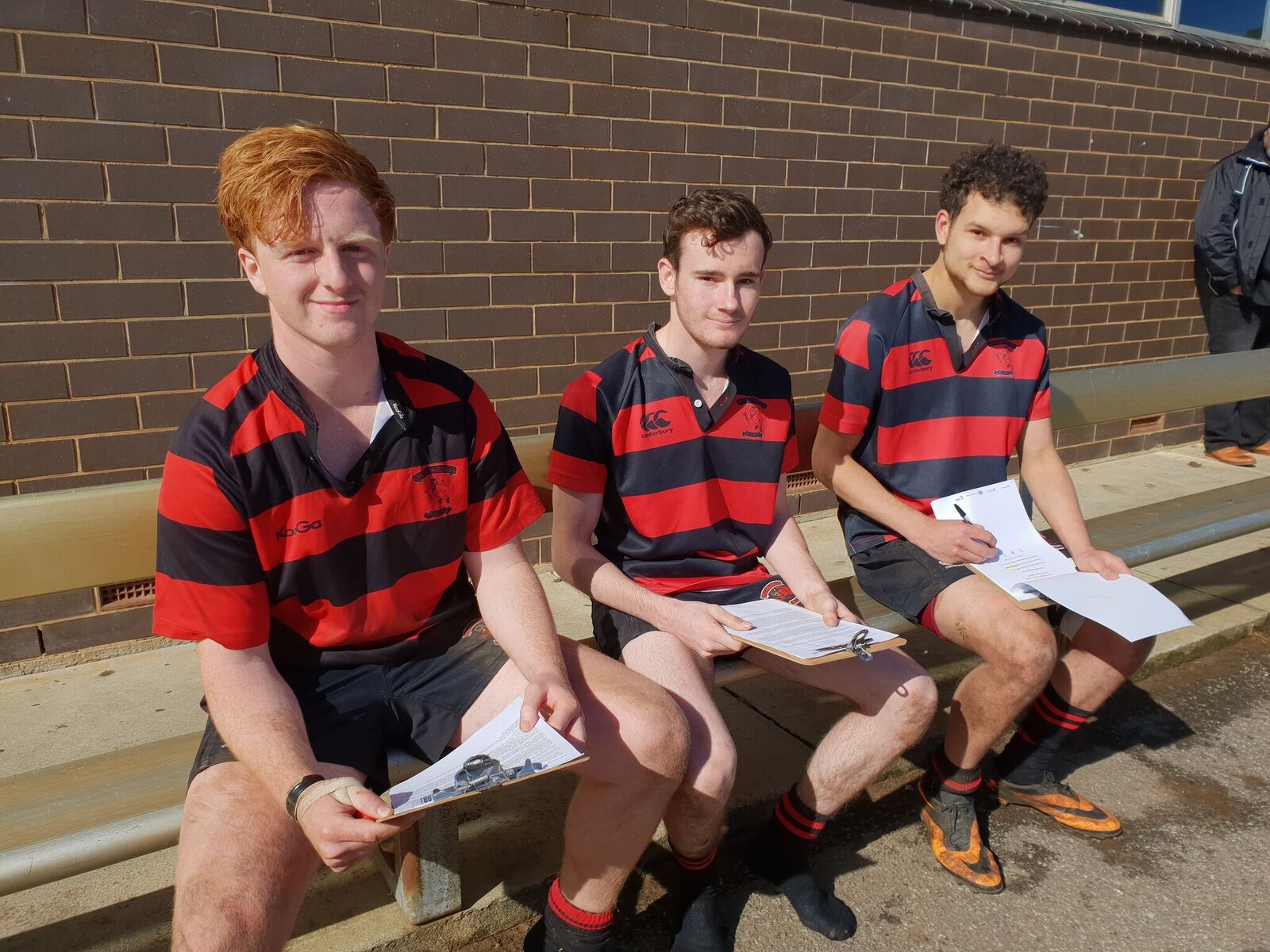

The large-scale study involved every under-18 and Colts rugby team in Victoria and South Australia, encompassing 231 players between the ages of 16 and 20.

The study looked into why homophobic language remains so common in sporting environments, and using those findings, researchers developed an education program designed to curb the use of slurs and harmful language.

The study found that most young rugby players have positive attitudes towards gay men and would be comfortable having gay teammates.

But researchers found that, despite this, players continue to use homophobic language.

Lead Researcher on Monash’s Sport Inclusion Project Erik Denison noted that these findings align with other significant studies into homophobia in sport in the last decade, including Out on the Fields and Come Out to Play.

“In recent years every major professional sporting organisation in Australia, and many around the world, including World Rugby, have made public commitments to stamp out homophobic language and behaviour,” Denison said.

“In Australia, these commitments were secured by organisers of the Bingham Cup in 2014.

“The Out on the Fields study clearly showed there is a problem with homophobic language in sport, our study is focused on finding solutions.

Our research will help sporting organisation to fulfil their commitments to stamping out homophobic language,” Denison said.

The program developed as part of the study was delivered to rugby clubs by six professional players from the Melbourne Rebels, including Rebels captain Tom English, and Denison and his team are now looking into its effectiveness.

“Our preliminary analysis found a disconnect between positive attitudes toward gay people among players while at the same time these same players were frequently using homophobic language and making jokes about gay people,” Denison said.

“This language would clearly make young gay people feel unwelcome in sport and it appears the straight rugby players also don’t like this language.

“We suspect this language continues because it is self-perpetuating,” he said.

“When boys start playing sport they would hear the negative language about being used about gay people by other, older males.

“We think this causes them to think this kind of language is both acceptable and how men are supposed to behave and talk in sport.

“Our findings suggest no one is telling the boys to stop using the language, and they aren’t stopping each other, so there is no reason to believe this will stop on its own, which is why it is important for sporting organisation to take meaningful action.”

81 per cent of players said they were confident they would stop others from bullying a gay teammate, and 83 believed a gay player would feel welcome on their team.

At the same time, nearly the same number – 78 per cent – said they heard other players using words like ‘fag’ and ‘poof’, while 59 per cent used such slurs themselves.

Of the study’s participants, only one identified as gay.

“I think the program we delivered to rugby teams this season is just the first step of a number of steps that we need to take to change culture and the language in sport,” English said.

“When we spoke to the boys a lot of them had never had this conversation about the language before or any education similar to this and so it’s really important that we don’t leave it here and we need to continue with this kind of education and other programs.

English said they had “mixed responses” to the program, with some players struggling to understand the impact of language.

“When we told the players that gay people have a six times higher rate of suicide than straight people and the language they hear is a big reason for this, I think it helps them really understand why homophobic language needs to stop.”

Caleb Whitton, captain of the Onkaparinga U18 team in South Australia, is studying to be a physical education teacher and said the program helped him better understand how language contributes to creating accepting environments.

“Being part of this study made me think back and realise there probably were things I have said that weren’t right to say, but I wasn’t paying attention and thinking about what the words meant to other people,” he said.

“I think players hear other players using the language about gay people, particularly younger players hearing older players, and I think it just becomes normal and acceptable.

“I think a lot of times people call each other homophobic names to be the tough guy, or the bigger man, and they trying to use the words to throw someone off and gain an advantage over them.

“I don’t think anyone means to cause harm to gay people and would probably stop using the language if they understood it was harmful.

“I love playing rugby because it’s a great sport and I don’t want people using language that takes the fun out of playing, and stops people from enjoying rugby as much as I enjoy the game.”

The research is supported by the Australian Government as well as Rugby Australia and Rugby Victoria, with added financial assistance from the Sydney Convicts and the Woollahra Colleagues.

You can read further information about the findings and the delivery of the program by clicking here.

Watch English and fellow player Sam Jeffries discuss delivering the program to one of the teams.