REVIEW: Lady Gaga’s Mayhem Ball — A Holy Experience, Especially For LGBTQ+ & Disabled People

There are concerts you attend and have a nice time at, and then there are concerts that rewire your brain chemistry, never to be forgotten — and Lady Gaga’s Mayhem Ball at Melbourne’s Marvel Stadium was the latter.

It felt like a pilgrimage, a mass; also a séance, perhaps elements of a Wiccan Esbat. But certainly a Catholicised, gargoyled dreamscape filled with sinners who know all the words. We would all have followed our Mother down the road straight into Hell had she asked, and then thanked her for the opportunity.

For me, a bisexual and chronically ill person who has loved Gaga — who is also bisexual, and lives with the same chronic illness as me — since the days of disco sticks and papa-paparazzi, it felt like coming home to someone who knows the inside of my body and my heart. The pain of it, the rebellion of it, and the resilience of it.

This wasn’t just a pop concert. It was a blueprint for how disabled people move through the world and create spectacular art, rendered in neon and marble and red velvet and fire.

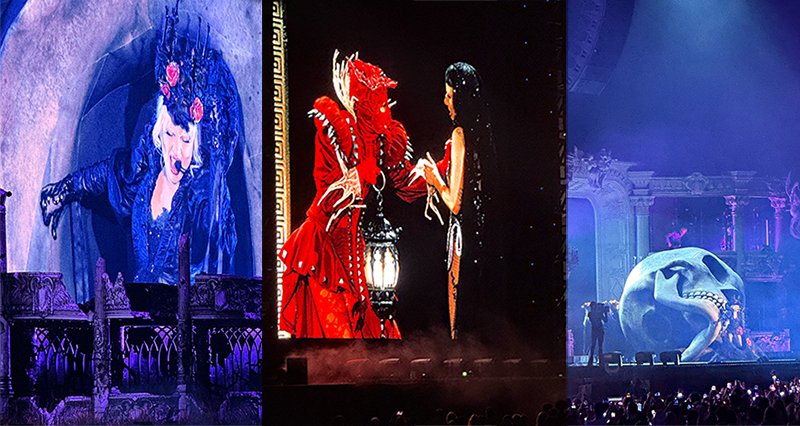

The religiously Gothic spectacle of my teen heart

The Mayhem Ball leans hard into Gaga’s spooky goth Catholic instincts — easily my favourite aesthetic of hers, the creepier and more religious, the better.

The ornate, complex set looked like an old, crumbling cathedral built by fallen angels. Veils, towering statues, detailed arches and shattered stained-glass projections; dancers moving like saints struck by lightning.

When she emerged in a mountainous skeletal corset to open with Bloody Mary, I felt the enormous crowd’s souls ascend. The stadium dissolved into smoke and religious ritual.

And when she shifted from Abracadabra straight into Judas without pause, the transition hit so hard it may have created a whole new generation of queer awakenings on the spot.

For me, hearing the Mayhem tracks live cracked open even more of the musical references she’s been playing with.

The 80s fingerprints — new wave and goth atmospheres of Siouxsie Sioux and The Banshees, the heartbeat synths of Kim Wilde, earworm echoes of Phil Collins, the tight samples of Michael Jackson. Live, the mix of nostalgia and reverence of the Mayhem album all made even more sense.

Amid all the aural and sensory witchcraft — the skulls, the veils, the pulsing faux-liturgical synths — something deeper was happening. Something my body recognised before my mind did.

Watching Gaga’s body, and seeing my own

Gaga and I share a diagnosis: fibromyalgia. A malfunctioning nervous system, which causes chronic pain and fatigue, and a whole host of other difficult symptoms. A lifelong condition that is extraordinarily complex to manage. It’s The kind of lifelong illness that rewires your life around its whims, demands concessions, reshapes the way you live, sleep, eat, fuck, love — and the way you make art.

Most people wouldn’t have noticed how she structured the show to manage her body’s needs — but I did. I recognised it instantly, like a secret language.

When she regularly shifted her body weight in her choreo, the way I do on flare days?

When she alternated costumes featuring between the towering heels she once used to live in, and flat shoes?

When, after a song with some intense choreography, she performed her next number lying down? (In a typically dramatic Gaga fashion of course, in a giant makeshift graveyard, writhing with skeletons in the dirt as if they were tender lovers).

When she leaned on a cane in one act, then crutches the next, then discarded them when her body allowed it?

When she wove musical interludes and stunning choreography from her dancers into the show’s narrative, meaning she had a few minutes break off stage every now and then?

I saw myself. I saw the way disability and artistry were beautifully braided together, just like the disability is braided into the artist herself. I saw a powerful woman setting boundaries in real time in front of tens of thousands of people, without apology or explanation.

And what struck me just as much was this: Gaga taking those small handful of breaks offstage — to change costumes, drink some water, and I can only assume to take a few moments to sit and rest — meant she handed the spotlight to her dancers and live band in a way other pop stars rarely do.

It wasn’t filler — it was intention. And by prioritising accessibility for herself, she created space for everyone else to get their bag and shine.

This is disability wisdom in action: accessibility and prioritising disabled people’s needs doesn’t make an experience like this smaller or lesser — it makes everything better.

In fact, it makes the world better for everyone. An extraordinary amount of things society universally benefits from (sloped pavements, automatic doors, captions, speech-to-text, ergonomic tech — just to name a few) began as accessibility measures for the disabled community.

With the Mayhem Ball, Gaga proved the same is true in art: build accommodations in from the start, and everybody wins.

Before the show even began, I realised I wasn’t alone in this. The number of disabled people arriving at the stadium was higher than any concert I’ve attended in my life. Mobility aids, braces, canes, wheelchairs, walkers. People managing pain, pacing themselves, resting on railings, checking their spoons.

It felt like arriving at the church of our spoonie patron saint — because clearly I’m not the only disabled person who identified with Gaga long before she spoke publicly about her fibromyalgia. We must have truly seen her long before the world did, because we recognised something familiar: the fight to stay tender, kind, passionate and dedicated while living in bodies that often catastrophise their own existence.

We weren’t tucked away or hidden at Mayhem Ball; we were present, abundant, visible. And for me, experiencing this less than a week after International Day for People with Disability, this felt like a holy experience.

The queer sacrament

Then came Born This Way.

Gaga looked out over the stadium and asked the queer community to make themselves known. And when she dedicated the song to “you — your pride, your strength, your beauty,” I felt split clean open with emotion.

I’ve been out and proud for a long time now, so I didn’t think I’d get too emotional hearing a song I’ve danced to in LGBTQIA+ bars for many, many years, live for the first time — but hoooooly fuck, was I wrong.

When Born This Way was released I was just a couple weeks out of my teenage years — still a baby queer, very lost, wholly terrified of my own brain, body and my future. And now here I was, years later, out and proudly queer and disabled, watching the woman who taught so many of us how to survive, stand before us, quite literally taking us to church. I couldn’t help it — I got teary.

If you ask me now, two days later, what it felt like experiencing this — I’ll tell you it was, for lack of a better word, holy. It was emotionally loud, cathartic, and freeing. Gaga once again provided a space queer people need: a cathedral built from pop, from pain, from identity — where we can scream, cry, heal, particularly right now, when anti-LGBTQIA+ and anti-trans sentiment and policy is rising.

Gaga: the gay icon I loved before I ever knew why I needed her

The stereotype goes that LGBTQIA+ people choose a gay icon when they’re a baby queer, and they never stop loving them until their last breath. I’m not usually one to perpetuate stereotypes, but some certainly have at least a kernel of truth to them, and I believe this is one of them – nearly every queer person I know has their ‘ride or die’ gay icon they’ve loved since they were a tween.

Boomers had icons like Cher, and Barbra Streisand.

Gen X had Madonna, Janet Jackson.

Millennials had lots to choose from, like Britney, Christina, and Gaga, who was the patron saint of the beautiful freaks.

She was always my #1 from day dot — it’s strange now to think I picked her so long before I knew what it meant to live with daily chronic pain, and I believe before she knew, too.

But as adults, becoming disabled queer artists in our own very different ways, my relationship with and adoration of Gaga has changed and deepened.

Seeing her live — my first chance after loving her my entire adult life— wasn’t just a tick on the bucket list for me. It was like a holy communion (one I actually wanted to take, this time) of wondrous disabled queerness.

I knew it was going to be phenomenal, but I did not expect to see my chronic illness so clearly on that stage, see accessibility so highlighted, see disability and queerness authentically celebrated in a way that is simply unparalleled. I thought I knew what to expect, seeing as the coverage of the Mayhem Ball has been so widespread, but our Mother of Mayhem and Little Monsters still managed to surprise and delight me — and I walked out genuinely emotional.

Because the world isn’t built for disabled and chronically ill people, and it keeps telling us that we can’t be spectacular, and our bodies and brains hold us back from making art that can change the world.

But Lady Gaga stood on that stage — smoke and stained glass, chessboards and giant skulls, fallen angels and graveyard dirt, flare pain, cane, and all — and said:

Watch me, bitch.

I did, and I couldn’t look away — and I’ll never be the same. Thank you for yet another life-changing experience, Mother 🐾♟️👑

All photos: Chloe Sargeant

Leave a Reply