Danny Vadasz: The Man Who Built A Gay Media Empire Starting In Melbourne

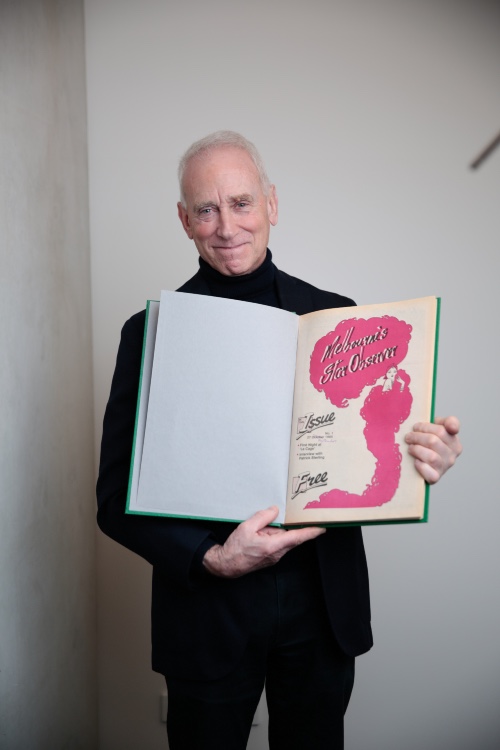

Thirty-six years after he had signed off on the inaugural Melbourne Star Observer, Danny Vadasz thumbed through the issue at the Australian Queer Archives’ new base at the Victorian Pride Centre on Fitzroy Street in late June.

The Melbourne Star Observer had its debut as a free fortnightly news magazine in September 1985 (though the cover page has a typo that says October), and was the second free, gay, news magazine published in Melbourne – the first was the Melbourne Voice, which wrapped not long after the Star Observer hit the stands.

Author Bill Calder calls the late 1980s and 1990s, Australia’s “golden era of gay magazines” in his book Pink Ink: The Golden Era for Gay and Lesbian Magazines. Calder reveals that at its height in the 1990s “more than five million copies of publications were printed annually, with revenues approaching $8 million a year.”

Vadasz had a significant role to play in that success.

The Driving Force

“Danny is quite entrepreneurial. He launched the Melbourne Star Observer in 1985, as a way to compliment his magazine Outrage,” Calder told Star Observer. “Danny was the driving force behind it all. He had planned to be a politician in the ALP (Australian Labor Party) but he got arrested during one of the Mardi Gras protests. He then swung his political ambitions to the gay revolution. Danny was driven by the cause. It was all about trying to bring change through these publications and yeah, he had an eye on making a business that was strong and viable.”

Vadasz, who turns 70 in July, concurs that his introduction to gay activism started with that arrest and the publishing of the names, photos and other details of arrested persons in the Sydney Morning Herald.

“I went from being completely apolitical to being an activist virtually overnight after the arrests at Paddington Town Hall square,” Vadasz recollects.

“I went through a transformational experience in 1978, getting arrested in Sydney. At that moment, I realised that I wasn’t going to be able to pursue a career as an openly gay man. Unless we changed, social norms and expectations so that it was possible for people who were openly lesbian or gay or LGBTQI to live a normal life and have a normal career,” says Vadasz of his changing gears from a career in politics to gay activism.

“A community couldn’t exist if it didn’t have an infrastructure and the gay community had no infrastructure. It wasn’t only that there was no gay media, there were no health and welfare services. There were no formal arts or culture, tradition in Melbourne. We had gay venues, but that was about it.

“There were a group of us who thought it was critically important that if the gay community was to evolve, if we were to lay the foundations that would eventually enable reform like marriage equality, then we actually had to create an infrastructure first. So, starting up the gay media was part of a process of consciously trying to build an infrastructure to hold a community together.”

The Queer Media In Melbourne

Vadasz was also behind the founding of other Melbourne institutions, including Midsumma Pride, the original gay business association and PFlag in Melbourne, and the Victorian AIDS Council, now Thorne Harbour Health.

In contrast to 1969, when there were no gay publications, the 70s saw the emergence of queer media in two waves.

“The first key newspaper Camp Ink started in 1970. During the early 70s, that coincided with the Labor (Gough) Whitlam government, Australia witnessed a sort of reforming progressive zeal and a number of gay publications started up. By the middle of the 70s, along with the fall of the Whitlam government, the economy had a downturn and everyone went back and was miserable,” says Calder.

The second wave started in the late 70s, with gay activism firing up, the opening of gay bars and venues and Mardi Gras. One of the epochal moments for the queer media in Australia was when Michael Glynn founded The Sydney Star in 1979.

At the time of his arrest in 1978, Vadasz was in Sydney attending the fourth national conference, and the next conference was scheduled to be held in Melbourne in 1979. Vadasz was tasked with preparing the conference newsletter, which went on to become Gay Community News in 1980, which then transformed into a national magazine Outrage.

“Remember that during this time HIV/ AIDS was emerging as the number one issue in the gay community. And we decided that a monthly publication, which is what Outrage was, wasn’t going to meet the needs of the community at a time when information and news about HIV AIDS was changing almost on a daily basis. A bit like the COVID epidemic,” recollects Vadasz. “You couldn’t rely on a publishing cycle of one month to keep up with what was happening and at that stage, the gay press was the only media in Australia that was covering HIV/ AIDS. It may have appeared occasionally in the mainstream press, but certainly, gay men which were the primary affected group at that time, relied entirely on the gay media, to let them know what was happening. We decided that we needed to produce something more regular than the monthly publication, and that’s when we decided to publish (Star Observer as a fortnightly).”

A Gay Publishing Tsar

In his book, Calder, who was the editor of Melbourne Star Observer in the early 1990s, reproduces a conversation with Vadasz where he reflects that this was time when he became “a megalomaniac and had illusions of grandeur about becoming some sort of gay publishing tsar.”

Calder went on to found a competing fortnightly magazine Brother and Sister, which triggered what he calls a “war of the newspapers” in the mid 1990s with the Melbourne Star Observer. Vadasz poured his energies into the mastheads with renewed vigour – the Sydney edition bringing out 30,000 copies every week and the Melbourne edition hitting 16-17,000 copies.

“It didn’t make money. it was virtually impossible in those days to profitably run gay media in Australia. The single exception to that would have been Sydney, which had a huge commercial entertainment gay market,” said Vadasz.

The “golden era” came to an end around 2000 for a variety of reasons – the weight of expectations and ambitions, sale of many publications to a new venture (that ended in a scam) and the dotcom boom/bust cycle. That is a story for another day.

“People like Danny and Jamie Gardiner stumped up a lot of their own money, there weren’t fortunes made in queer publishing at the time, and most lost a lot of money in the process. For many of the publishers and journalists it was a passion project, part of their long-term activism,” says Nick Henderson, committee member and curator of the Australian Queer Archives, provides an overview of the period.

“At the end of the day, there was some really fantastic journalism produced during this era, and they really were a key source of information for the community, on HIV/AIDS, parties, personal ads and more, they were a vital part of helping build our communities,” adds Henderson.

Community Has Come A Long Way

After selling off his gay media empire, Vadasz moved on to health care and is presently the CEO of Health Issues Centre. Vadasz, who has not been part of gay media for around two decades says he has no regrets.

“The gay community has come a long way and it’s really satisfying for me to see how far we’ve come as a community. The fact that we now have a Pride Centre that’s underwritten by government funding, the fact that we have a vibrant culture, that Midsummer has lasted all these years, then we have forums for creativity and celebration like the film festival and that it’s incredibly satisfying because when we began this journey there was nothing. Literally nothing,” reminisces Vadasz.

“And we, we must have had a ridiculous amount of optimism and youthful energy to think that we could change all of that. Obviously there are still battles, and people are still struggling with issues, whether it’s around gender or whether it’s around issues like marriage equality. It’s important when we’re feeling frustrated and exasperated to just look back and say how far we’ve come and that should be enough to convince anybody that nothing is impossible!”