Ten lessons from the Tasmanian gay law reform debate that will win marriage equality

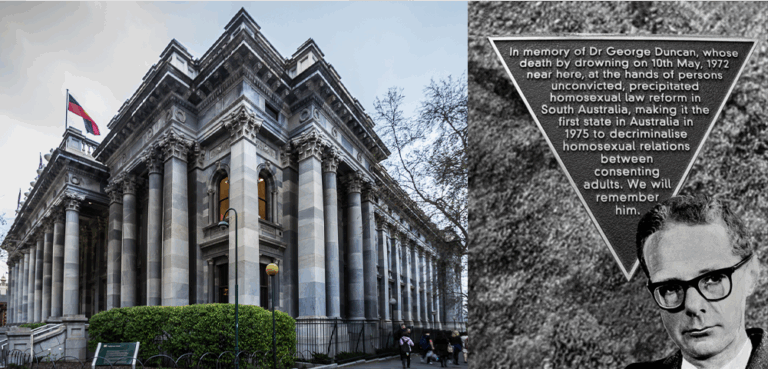

May 1st 2017 is the twentieth anniversary of the decriminalisation of homosexuality across Australia. On that date the Tasmanian Upper House finally agreed to remove the state’s laws against sex between consenting adult men in private, a crime so serious that it carried the highest penalty anywhere in the western world – 21 years in gaol.

Tasmania was remarkable not only because its laws were so severe and it was the last state to repeal them, but because the campaign for reform was so hotly contested and so emphatically successful. For a decade the issue was in the news every day. Supporters were arrested, opponents held angry rallies and MPs tried many times to navigate bills through Parliament.

As Tasmania fell further behind the rest of the western world, the UN, the federal government and the High Court were all drawn in. There was even an attempt to hold a plebiscite. But when decriminalisation finally occurred there were none of the caveats that were put in place in some other states, the hate campaigns stopped overnight, and soon after decriminalisation Tasmania adopted the best LGBTI anti-discrimination and relationship laws and policies in the nation. These dramatic changes were based on an equally dramatic shift in popular opinion. Tasmanian support for decriminalisation was 15% below the national average when the campaign began and 15% above when it ended. In a few short years, Tasmania went from the worst state on LGBTI human rights to the best.

Many elements of the Tasmanian debate echo in today’s marriage equality debate. Tasmania was last like Australia is last. Tasmania took a decade like Australia has taken a decade. Decriminalisation was in the news constantly, as is marriage equality. Opponents of equality predicted Tasmania would slide down the same slippery slope they say Australia will slide down today. Both campaigns were long slogs against the odds that drew in large numbers of people on both sides. So what can Tasmania teach us about making change today? Here are ten lessons from the successful Tasmanian gay law reform debate that will help us win marriage equality.

1. Liberals can lead

For years, the Tasmanian Liberal Party angrily opposed decriminalising homosexuality. Some Liberals praised the state’s anti-gay laws for their “educative value” while others whipped up hate at anti-gay rallies. That all changed in 1996 when Liberal Premier, Tony Rundle, allowed his MPs a free vote on the issue. It was this free vote that allowed decriminalisation to pass a year later. Since then Tasmanian state Liberals have led the way. Free votes have seen a majority Liberal support LGBTI parenting rights and marriage equality. In April, Will Hodgman became the first Liberal Premier to apologise to those convicted under our former laws.

One key to this transformation was non-partisanship from advocates. Support across political parties was essential to moving decriminalisation forward, as it is for moving marriage equality forward today. It’s vital that we encourage supporters of reform in all parties rather than put our eggs in the basket of one particular party. The other key to the transformation of the Tasmanian Liberals was the 1996 election where it was clear to everyone the Liberals’ opposition to marriage equality had cost them the votes of constituents heartily sick of anti-gay hate. My hope is that the federal Liberals can learn from Tasmanian history and allow a free vote so marriage equality can pass within this term of Government. But if the Liberals don’t learn, and it takes an election where their resistance to change costs them seats, so be it. I’m confident they will be sobered enough by that experience to allow a free vote from then on.

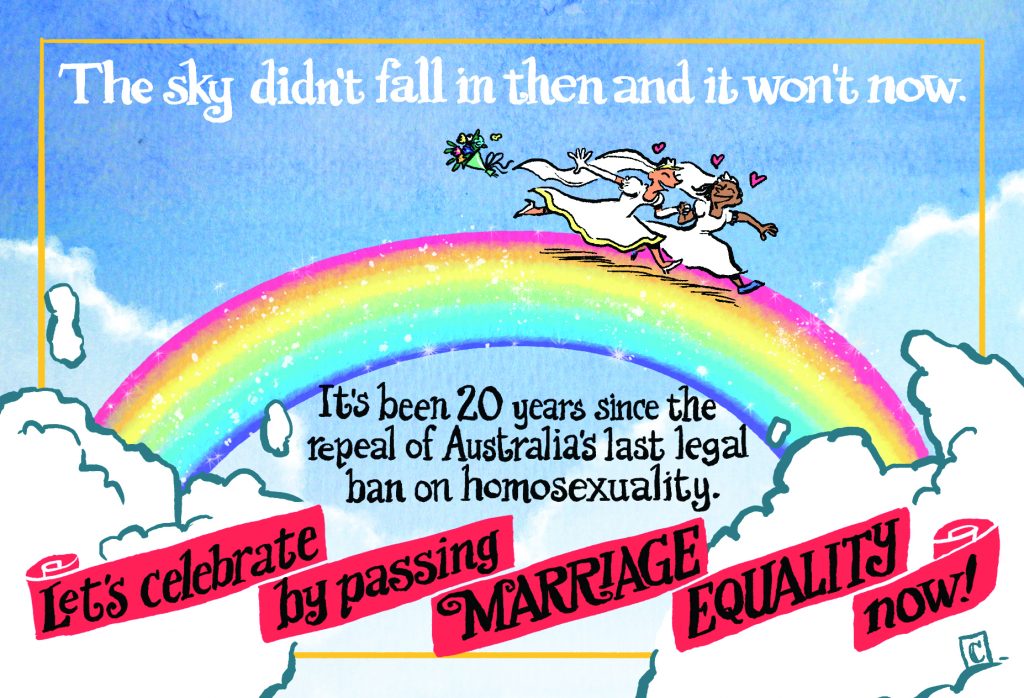

2. The sky didn’t fall in then and it won’t now

Opponents of decriminalisation in Tasmania predicted it would lead to the promotion of gay sex in schools, the normalisation of gay parenting, the legalisation of incest and bestiality, even lost trade opportunities in Asia. Sound familiar? The same slippery slope is predicted by today’s opponents of marriage equality. Of course none of the dire predictions of Tasmania’s anti-gay advocates came true. The sky didn’t fall in then and it won’t fall in now.

In Tasmania we addressed the apocalyptic fears of gay law reform’s opponents directly. For example, when they said teachers would be forced to teach children about anal sex we responded by talking about bullying of LGBTI students and why this should be tackled. As a result, Tasmania adopted some of the nation’s best LGBTI schools policies after decriminalisation. In the same way, marriage equality advocates should see the current attempt to conflate marriage equality and schools as an opportunity, not a challenge. Rather than hoping the Safe Schools fuss will just go away, advocates should be using it to highlight the damage done by anti-LGBTI prejudice in the school yard. This will ensure sensible school policies are adopted, if not before marriage equality occurs, then swiftly after.

Opponents of gay law reform in Tasmania also did something else that was remarkably similar to today: the tried to legitimise their morally bankrupt case by playing the victim. In particular, they tried to make the debate all about their rights and freedoms being taken away, including religious freedom and freedom of speech. In Tasmania that argument gained no traction at all. It was no match for the personal stories LGBTI people told of the pain inflicted by real ill-treatment. The marriage equality campaign has featured some compelling stories of the disadvantage caused by inequality, but it must do more if the faux victim narrative of the opponents of reform is to be disrupted.

3. There are ways around roadblocks

When the Tasmanian Upper House repeatedly and angrily threw out decriminalisation in the early 1990s we decided to go around it. We took Australia’s first case to the UN Human Rights Committee. When the UN decided in our favour we lobbied the federal government to override the Tasmanian laws. When it didn’t go far enough we went to the High Court for the declaration of invalidity we needed.

The marriage equality campaign has drawn on this history. States have tried to pass laws allowing same-sex couples to marry and attempts have been made federally to recognise overseas same-sex marriages under Australian law. As we face yet another roadblock, created by the failure of the Liberal Party to allow a free vote, we must return to these alternate paths. The High Court’s decision against the ACT’s marriage equality bill did not preclude a state same-sex marriage bill that is drafted to be more constitutionally resilient. We should also explore new routes including a case to the UN Human Rights Committee. There is a risk the UNHRC could not find in our favour, but that risk is no greater than the risk we faced with our Tasmanian UN case.

4. Civil disobedience works

When the Hobart City Council banned a gay law reform stall from Salamanca Market in 1988 130 people defied the ban and were arrested. This put the issue on the front page for the first time in Tasmanian history. Six years later when gay men turned themselves in to police with details of their illegal sexual activity, support for decriminalisation solidified in the general population and opponents went from being aggressive proponents of a gay-free Tasmania to increasingly irrelevant defenders of an archaic law.

Civil disobedience worked then and it can work again now. There are many different ways to show principled opposition to discrimination in the Marriage Act. The one constant must be that this disobedience is non-violent, non-confronting and crystal clear in its central message. Anger, arrogance and muddled messages have no place in the kind of civil disobedience that changes lives and nations.

5. Go to the people!

A successful campaign, like a good symphony, relies on different instruments playing harmoniously together. As well as looking at new legislative and judicial paths forward we have to do more grassroots work. In Tasmania LGBTI community members spoke to service clubs, sports groups, political party branches and other organisations across the state. It could be tiring but it made a real difference to public attitudes in a small, interconnected society like Tasmania.

The marriage equality campaign has borrowed this strategy from Tasmania, sending speakers around the nation. These meetings tend to draw people in from across the community and to focus on lobbying local MPs, which is very important. But the reach, and the investment of resources, must be greater. As in Tasmania, local speakers should be addressing established groups in terms that are meaningful to those groups. This is the key to fostering a deeper understanding among Australians about why marriage equality matters so much.

6. Real change comes from forbearance and forgiveness

Even more important than talking to people where they are about what matters to them is how we talk to them. In 2015, when Telstra withdrew further support for marriage equality at the behest of the Catholic Church, a Telstra employee pleaded with me to “call out bigotry where we see it”. I responded by talking about the anti-gay rallies I mentioned earlier. These were harrowing for me because they occurred in the communities I grew up in. I could have dismissed those attending as “bigots” but that would have just reinforced the barriers that were already so destructive.

Instead, I kept reaching out my hand to these communities, over and over for years on end, until it was finally accepted. Yes, that hurt. Yes, it took immense patience and the capacity to forgive. Yes, you need to hold the people you are reaching out to in higher esteem than they hold you. Especially painful was being accused of hating those for whom you only wished the best. But in the end it is all worthwhile. The profound transformation forbearance and forgiveness create is worth every jeer, jibe and scowl along the way.

I took this ethic with me into the marriage equality campaign and I’m proud it took hold. Indeed, advocates in other countries like Ireland and New Zealand have praised the example set in Australia and have adopted it as their own. But the frustration and anger each of us naturally feels at being demeaned and diminished is always with us. We must constantly remind ourselves that when we lambast others instead of reaching out to them the greatest damage is done to ourselves. Every wall we turn away from and every bridge we fail to build cuts us off from a new horizon of hope.

7. Marriage equality is about big things

Another way to win hearts and minds is to make it clear that marriage equality is about big things that really matter. The marriage equality campaign has dwelt on qualities we all value, love and commitment, fairness and equal opportunity. But it has also sought to make marriage equality a small target, especially in response to the possibility of a plebiscite. This has meant playing down the consequences marriage equality so as not to frighten middle-ground voters. It’s time for that to end.

We won decriminalisation in Tasmania because the issue became a prism through which tens of thousands of people viewed Tasmania’s past and future. The decriminalisation debate reached into Tasmania’s deep past, finally addressing how our identity as Tasmanians was defined by the close association our forebears made between sodomy and the hated stain of convictism. It looked forward to a much better future for LGBTI people free of the poison of state-sanctioned prejudice. Indeed, it held out the hope of a better future for all Tasmanians. The question before the Island was not just, “will we stop criminalising gay people”, but also “will we become a more open, inclusive society”.

In the same way, marriage equality is about more than same-sex couples walking down the aisle, as important as that is. It is about our national identity. It’s about banishing our dark, homophobic past. It’s about whether we really believe those democratic values we expect migrants to take to heart. It’s about the egalitarianism our forebears valued so highly. It’s an affirmation that moral improvement and social progress are possible and desirable.

Marriage equality will have huge consequences for the LGBTI community and for the country. It is the door to LGBTI people being accepted as fully human and equal citizens. It will remake Australia as a place that is open to the world, values itself and embraces all those who call it home. It will dramatically shape our futures, individually and collectively. This message about the sweeping scope of marriage equality is something everyone needs to hear.

8. The biggest thing of all is belonging

Tasmanians, like many island peoples, have a strong sense of place and belonging. That sense of belonging can be so compelling that if prejudice threatens to cast us out, we will battle that prejudice with all our might. That’s certainly what motivated many of the key campaigners who sacrificed so much to see homosexuality decriminalised.

There were other reasons we worked for gay law reform: love of justice, belief in human rights, the desire to live life unmolested by the law. But belonging is different to the rest. Unlike equality it cannot be seized. Unlike inclusion it cannot be bestowed. It only comes through a long, arduous negotiation between those who feel they define an identity and those who know the definition falls short. In the course of that negotiation both parties are transformed for the better. Unlike the other aspirations that motivate supporters of reform, a sense of belonging pre-exists the prejudices that threaten it. It is not a prize to be won but a promise to be fulfilled, a promise that people will fight to their dying breath to have honoured.

Marriage equality is also about the fulfilment of the promise that we belong, whether it be to our families, our communities, our faith, our profession, our beloved sporting code, our nation, or to the land beneath our feet. How can it be otherwise when marriage remains such a key social institution and equality such a fundamental aspiration? I sense the ache to belong in so many of the people who campaign for marriage equality. It’s time for us to name and embrace it, if only so we understand better what drives us forward and how that drive will elevate us, those dear to us and Australia.

9. We don’t have to accept the low road to reform

Many people have forgotten what extraordinary measures were taken by opponents of decriminalisation in Tasmania to derail the movement for reform. Legislation for a plebiscite was tabled by Upper House members. Laws criminalising the promotion and encouragement of homosexuality were also proposed as the decriminalisation of gay sex drew nearer. Both moves failed miserably.

The parallels with today are obvious: opponents of marriage equality are trying to delay marriage equality with proposals for plebiscites and to dilute marriage equality’s impact with caveats allowing discrimination against same-sex couples in wedding services. So what can we learn from Tasmania about avoiding these outcomes?

The features of the Tasmanian campaign that I have already described put us in a position strong enough to ensure we didn’t take the low road to reform. We had made gay law reform a metaphor of something greater than itself, we had taken that message to tens of thousands of people across the island, we had shown we were willing to take risks to achieve reform, we had modelled what we wanted Tasmania to become. Most of all the principles that underlay the movement for decriminalisation – equality, inclusion, toleration, belonging – had been so evident and gathered such strong support it was easy to deploy them to defeat unacceptable compromises.

Marriage equality is, or could easily be, in the same position. Support for it is strong. The principles behind it are clear cut. To defeat proposals for public votes and for caveated legislation we must not be afraid to deploy this support and these principles as often as necessary. It won’t distract from making the case for marriage equality, as some fear. It will enhance that case by reinforcing the values that motivated us to support marriage equality in the first place.

10. Consultation and democratisation are essential

During the Tasmanian decriminalisation campaign every major decision was taken by a committee of LGBTI people that held open meetings and whose members were intimately linked to the wider community of LGBTI people and our allies. Consultations were regular. Rarely, if ever, was there division about the way forward.

It’s time for much wider consultation and greater democratisation in the marriage equality campaign as well. The people at the top are smart, capable and have the best interests of the issue in mind. But there are critical moments in the campaign – the push for a plebiscite or the proposal of caveats to marriage equality legislation – when consultation must extend to as many LGBTI people as possible and when decision-making must be more democratic.

This will allow more people to share the burden of the choices to be made and the outcomes from those choices. It will remove any suspicion that interests other than that of the LGBTI community are at play. It will give the leaders of the marriage equality campaign the strongest mandate possible. It will allow them to draw on a bigger pool of energy and ideas.

Australia is walking the final leg of the long road to marriage equality. As we get closer to the end let’s make sure there are no longer insiders and outsiders. Let’s make sure we all walk home together.

Dave I’m not certain how me changing the brand of beer I drink is ‘screaming at’ anyone.

I’m also trying to work out who has stopped supporting me. Perhaps you could discuss some evidence for your assertions.

Hi Harley, I’d be fascinated to know why you changed beer brands. I was referring to the calls for hotels to pull Coopers from their taps for an episode which was one of the most mistaken claims of homophobia I’ve ever seen. That’s doing much more than exercising individual consumer choice.

The fact is that when the label homophobic is put out there, it has to consider both what has been said or done and the context in which that has occurred. Coopers funded a bible group to make some videos, the video which came out featured two Christians discussing same sex marriage, both are politicians from the conservative side of politics, one of them put forward a sensible and eloquent case for same sex marriage. So Coopers, albeit inadvertently, managed to get probably the most pro SSM argument ever onto a bible website which only influences Christians, it wasn’t a mainstream news site or anything. Don’t take my word for this argument, I’ve significantly plagiarised it from Rodney Croome speaking on Radio National’s Drive program (audio available on the RN Drive page on the ABC website if you’re interested).

And for this they are called homophobic and subjected to a public backlash from elements of the pro same sex marriage lobby.

The result is that when something actually homophobic happens, too many people write it off as just a bunch of whingers again and don’t consider the injustice which is occurring. And that is bad news for some cases which deserve to be taken more seriously.

I hope that expansion of my views makes more sense. Cheers.

Excellent article from a great advocate. I think if Rodney Croome has taught us anything it’s the importance of choosing the right battles and the right tactics. People are most likely to move from a regressive to a progressive position if they are left to consider injustices for themselves rather than be screamed at. There are many great discussions and advocates which are achieving this but some actions (the decision a couple of years ago not to invite Turnbull to the Mardi Gras, the calls to boycott Coopers for getting one of the strongest pro-same-sex-marriage messages into Australia’s Christian community) lose more support than they win.