Born This Way: Turning Up Tolerance or Interrupting Inclusion?

MY kids are big fans of Macklemore, and his album The Heist is on high rotation on our road trips. We’re all up for putting our hands in the air and car dancing.

For anyone not familiar with Macklemore, he’s a white American rapper who, among other things, achieved some notoriety for his support of marriage equality in the song Same Love, which condemns homophobia. It was a huge hit, performed at the 2014 Grammys where it was nominated for song of the year, and featured an ear-worm chorus of Mary Lambert’s gorgeous vocals: “I can’t change / Even if I tried / Even if I wanted to.”

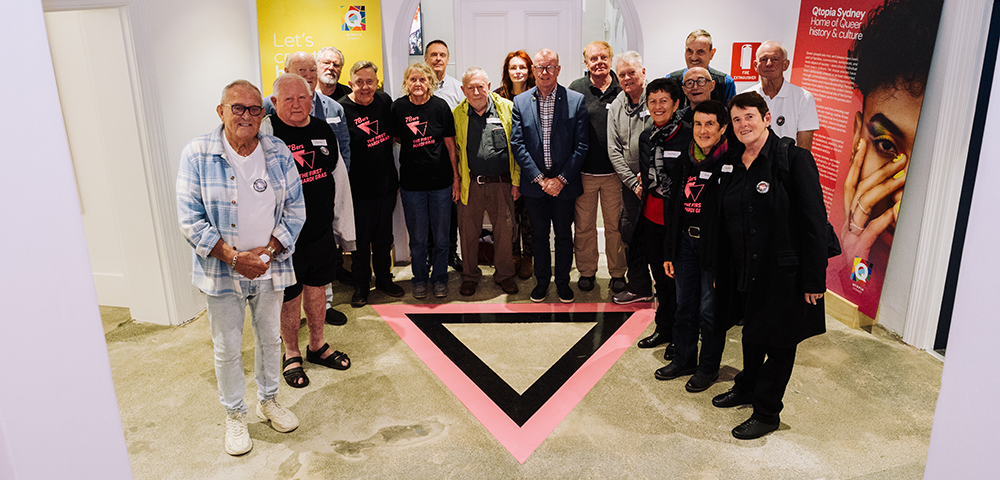

Now, my kids are part of a modern family. They march in Mardi Gras, they have friends, family and teachers who are from all parts of the LGBTI spectrum. Like many kids, they have strong views about things that are fair and unfair, and they have a strong sense of injustice about issues like marriage equality and homophobia.

However, in talking about the song it became clear that one of the reasons this song really resonated with them — and presumably the music-buying public — is that it makes the point that homophobia is fundamentally unfair because LGBTI people can’t help it. We’re just born this way and we can’t change, even if we want to.

I don’t want to suggest that there are not lots of people for whom this is the case. I have plenty of friends who tell me that they knew they were different from other kids because they were attracted to kids of the same sex in pre-school. Or that they felt they had been assigned to the incorrect gender from as early as they could remember. And intersex people are born with sex characteristics that don’t fit medical norms for female or male bodies.

But for some of us, this isn’t necessarily the case. While newspapers can always be counted on to report on research about the possible factors behind sexual orientation and gender identity, it seems that the scientific jury is still out. At a time when LGBTI issues are up for public debate — in just the last few weeks marriage equality, trans visibility and the Safe Schools program have been in the headlines — it’s important to consider how advocates should best go about changing hearts and minds. With the Turnbull Government still backing a plebiscite on marriage equality, the headlines may well get worse before they get better.

It’s important to remember this isn’t just some kind of theoretical debate. Research shows that despite increasing legal protection from work discrimination, LGBTI people still suffer from discrimination and harassment in the workplace. People are denied employment, fired, passed over for promotion, or given less desirable assignments or compensations.

Research also indicates there are consequences for individuals and organisations where people feel unable to be honest about their sexual orientation or gender identity at work.

One US survey of almost 3000 LGBT employees 48 per cent of respondents reported being closeted at work, with substantial negative consequences. In short, those who were out flourished at work, while those who were in the closet languished or left.

Workplace discrimination, of course, reflects broader community attitudes. In Australia 20 per cent of trans people, 19 per cent of intersex people and more than 15 per cent of LGB people report suicidal thoughts or attempts, with young people particularly vulnerable. One Australian study of more than 3000 same-sex attracted young people found 61 per cent reported homophobic verbal abuse and 18 per cent reporting physical abuse.

So is making the case that we’re “born this way” going to change the kind of views that result in such discrimination? Recent research suggests perhaps not, with a study by researchers at the Universities of Tennessee and Missouri-Colombia suggesting that promoting a “born this way” ideology is not likely to substantially reduce homophobia. One of the authors of the study, Professor Patrick Grzanka, told US media site Fusion that people might believe LBGTI people were “born that way” and that “sexual orientation is not changeable”, but it did little to influence whether or not they also held homophobic views.

In her 2014 book The Tolerance Trap: How God, Genes, and Good Intentions Are Sabotaging Gay Equality Suzanna Danuta Walters argues: “How we experience our sexual identity is produced in and through a multitude of factors, including our political commitments, our geographical locations, and our racial/ethnic identifications. And, to add to the complexity, desire itself shifts and changes over the course of a lifetime.” She goes on to explain it “is not captured by the weak language of acceptance or the tepid embrace of tolerance but rather by the richness of real inclusion and robust integration and investment”.

Similarly, in a new book Equality Is Not Enough: Seeking Full Liberty for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People Andrew Park writes that while the LGBTI movement must continue to work for full legal equality, we must also keep in mind that “good laws do not necessarily mean good lives”. He suggests our focus needs to shift to increasing the well-being of LGBTI people in improved health, income, education, and democratic participation. In essence, we must emphasise LGBTI people are able to live the lives they want.

My take on Park’s book is it is critical we emphasise social and economic inclusion for LGBTI people, not simply tolerance of diversity. To do that we need to move beyond simple explanations that biology is destiny.

In many ways, workplace inclusion practitioners have developed a model that LGBTI community advocates could look to. We know some of the best developments in diversity and inclusion in recent times, like all roles flex initiatives, are those that are able to support all employees, regardless of the boxes we tick about our personal characteristics. Emphasising the benefits of inclusion over simple diversity, and workplaces that are inclusive of all, is an ideal that we should also work towards in the wider community.

It is time for all of us to think about how we can ensure our workplaces, schools and communities can be truly inclusive of people across all sexual orientations and gender identities. Merely tolerating us because we “can’t change the way we are” just isn’t enough.

Jo Tilly is the Research and Policy Manager at Diversity Council Australia (DCA). This piece is an edited version of one originally published on DCA’s website: www.dca.org.au.

__________________________________

**This article was first published in the April edition of the Star Observer, which is available now. Click here to find out where you can grab a copy in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, Canberra and select regional/coastal areas.

Read the April edition of the Star Observer in digital format:

__________________________________