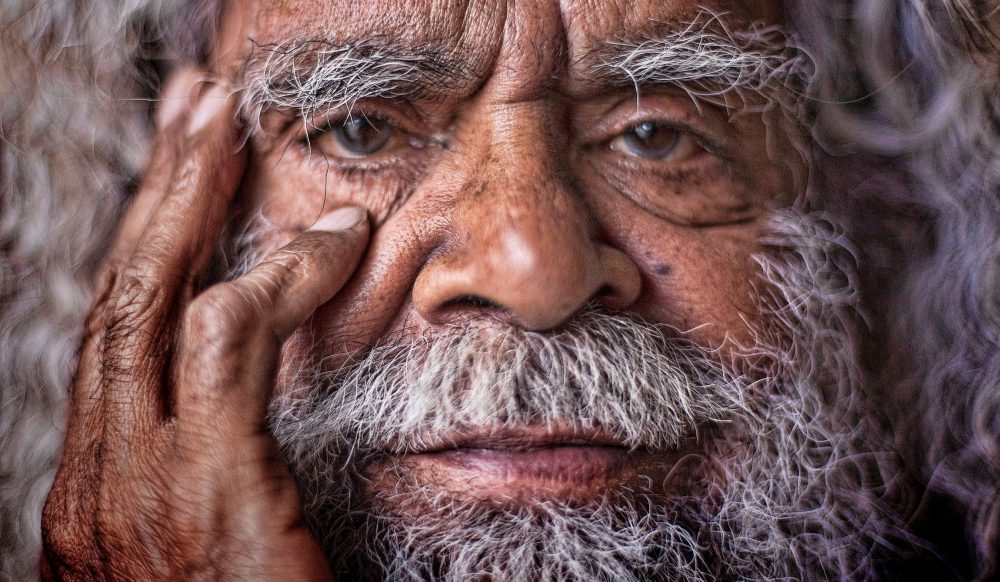

Uncle Jack Charles on helping incarcerated Indigenous youth – gay and straight alike

Indigenous elder Uncle Jack Charles is pushing for community centres around Victoria to help incarcerated youth, gay and straight alike. Matthew Wade reports.

***

As the rates of Indigenous incarceration in Australia continue to rise, Indigenous youth remain disenfranchised, growing up in a society systematically designed to oppress them.

According to a recent report by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), while Indigenous children make up seven per cent of the general youth population, they make up 54 per cent of young people in youth detention centres around the country.

This over-representation is present in every state and territory, with Indigenous youth four times as likely to be in youth justice supervision in Tasmania, and 27 times as likely in Western Australia.

For Uncle Jack Charles – a gay, Indigenous elder born to a Bunurong mother and a Wiradjuri father – the issue of Indigenous youth in detention centres is a personal one.

“We need to stop the tides of young ones going into our lock-ups and prisons,” he says.

“When they get there, there are three police officers assigned to a prisoner, which makes it overbearing – it’s hard to reach out to anybody when they have such anger towards the system and the officers.”

When he was younger, Uncle Jack was forcibly removed from his mother as a member of the Stolen Generation, and found himself regularly moving through Victoria’s prison system as the result of criminal activity.

Now, he regularly visits prisons and detention centres to speak with young inmates, sharing his story in the hopes that it will strengthen their resolve to avoid crime once they’re let out.

More recently, he’s been pushing Premier Daniel Andrews and the Victorian Government to invest in the development of Indigenous community centres around the state, particularly in regional areas.

“We need community centres,” he says.

“An Indigenous community centre is an establishment, a sanctuary for Aboriginal people where the community can get together and talk about our personal issues with each other… it’s the only way forward.

“I have to convince [Daniel Andrews] to take Aboriginal people here in Victoria seriously. Not that he isn’t, but sometimes the government needs direction from elders with lived experience who can see a way forward to address the systemic issues that are confounding us and putting us behind the eight ball.

“We need an injection of serious funding to buy our own buildings to use for community centres.”

Uncle Jack adds that in regional towns, centres like these are vital. He regularly speaks with young people in detention centres who are from Horsham or Shepparton and have nothing to go back to in their country towns, leaving them at risk “of fucking up again, because there’s nothing for them to gravitate towards”.

“When I visit [the centres], I usually hang around and wait for the young ones to approach me before I leave, and there’s always a mob of them that do come up and talk to me,” he says.

“They thank me for hearing my journey, because I let them know they have nothing to be ashamed of.”

An axiom often left out of conversations around Indigenous incarceration is that a number of people imprisoned identify as both Indigenous and LGBTIQ+.

Uncle Jack believes communities, both white and queer, need to recognise LGBTIQ+ Indigenous youth and join them in the fight against a prison system disproportionately stacked against Indigenous people.

He says it’s important for people to understand that LGBTIQ+ Indigenous people exist, and to work with them to build a better society.

“We’re trying to impress upon white communities to start taking Indigenous history seriously, because we’re on the same battleground,” he says.

“And to let them know that there are many Aboriginal people who are gay, both men and women, and that we’re so proud we’ve made our mark and stamped our ground.

“I notice that gay people in youth detention centres and prisons are often a wealth of information for the young [gay] ones struggling to find their way in a jail setting – there are many people with gay inclinations who give a chop out to those who seem to be frightened, existing with a bunch of straight, heavy crims.”

Uncle Jack will be taking part in a number of speaking events this month, aptly titled ‘A Night With Jack Charles’, where he hopes to talk about his life as a gay, Indigenous man, and push for communities to come together and work towards building Indigenous community centres.

“[Audiences] will hear a frustrated old coot sermonising about how we should be more collaborative as people, as Melburnians, and why we need community centres,” he says.

“They were all abandoned once the councils saw that too much black money was being embezzled and distracted, and they were no longer willing to fund our centres.

“But we need another round of them.”

When it comes to younger LGBTIQ+ Indigenous people, Uncle Jack wants them to be true to themselves.

“But always watch your back, because we’re not in a gay world,” he says.

“We’re living on the fringe of society, like Indigenous people, we’re fringe dwellers.

“So us gay and Indigenous mob, we’re fringe dwellers twice over, and that’s what gives us great strength.”

Read more: ‘It’s about time we start supporting other people in their fights against injustice’