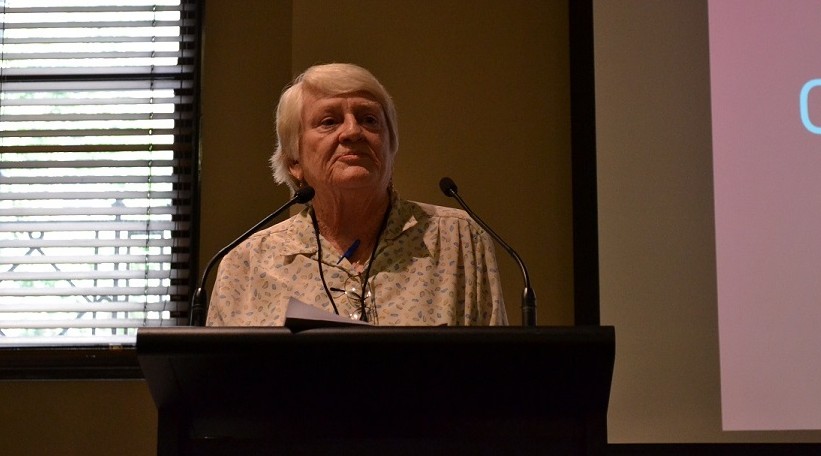

Former Queensland Police officer Jill Bolen gave a version of this talk at a session of the National LGBTI Ageing and Aged Care Conference 2014 at the Melbourne Town Hall. While this is Jill’s own written version of the story, the talk as given was slightly modified.

THANK you for allowing me the opportunity to share my experiences with you.

Like members of the broader community, lesbian community have a range of life’s experiences. I am 63 years of age, and my working background was predominately in policing.

This is part of my life’s story. I came out as a lesbian in my late teens, and lived a life whereby my sexuality was not a primary concern for me — initially. As I was a state public servant at the time, and started to attend social events, things changed.

In the early 1970s in Brisbane, the usual term given to the LGBTI community was the CAMP community. CAMP was an acronym for the Campaign Against Moral Persecution. We had a number of hotels, and the CAMP club, where we would gather for social events and dances.

At that time, the police would park opposite the CAMP Club, and when they raided the Club premises, many of us would step out of the windows onto the awning. The harassment knew no bounds, but the gay males were harassed more broadly than the lesbians; that was because consensual sexual activity between men was an offence under the Queensland Criminal Code.

Many LGBTI folk had experienced much harassment by police, and also, they had been sacked from their jobs when their sexuality became known in the workplace. It was then I realised that life was not as carefree for our community as for many other sub-groups within society.

In Queensland, most of the venues we attended at that time included both lesbians and gays as their patrons. It was a time when, for work purposes, many a lesbian would take a gay man (and vice versa) to special events to avoid being outed. The threat of losing one’s job because of one’s sexuality was real. It was not something just imagined.

In 1973, I joined the Queensland Police. Things went well with my career, generally, until 1975 when a male colleague told me that a bisexual woman police officer was reporting my sexuality to senior officers. I asked what I should do, and he said do nothing, but keep it in mind.

Nothing much more happened, overtly, until 1977. I had been a detective and sexism was an issue. When I was to go to Adelaide for an extradition, that trip was disallowed and a male detective was sent in my place. Rather than put up with this, I applied for a transfer to uniform in one of the housing commission areas of Brisbane.

Despite the hurdles of single females obtaining finance for a house, I had managed to purchase a house in an outer suburb and was, at that time, living with my partner who was also a policewoman. Life was good, but things were soon to take a turn for the worse.

I was at the Brisbane Coroner’s Court waiting to give evidence when my partner came out of the lift looking quite stunned. I asked what was wrong because things were fine when we had breakfast and left for work that morning.

She had been called in to the head of the C.I. Branch and was interviewed about our relationship. The interviewer asked her if she was in a lesbian relationship with me. She admitted she was.

Various questions were asked which indicated they knew of our socialisation and activities. She was also asked if her family knew of this situation. She was then told to come to the court and bring me for interview when I had finished.

After giving evidence, on arrival at the CIB Headquarters, I made calls to some other lesbians in the police. I explained what was happening and recommended they not attend without a lawyer.

I was then interviewed, and readily admitted my sexuality, and said that it had nothing to do with my job. I asserted that I was more competent and capable than some of my heterosexual, male counterparts; there were few female police in that era.

At this stage, the Inspector taking notes of the interview asked me how to spell heterosexual. The interviewer walked out of the room; I think he went out to laugh.

I went through the same process as my partner. I asked them what the purpose of the investigation was. They gave no indication other than to say that others would be interviewed. Seven of us were interviewed.

In the following weeks, my partner was transferred to Longreach in central Queensland, and I was transferred to Mt. Isa. In speaking with senior officers sympathetic to my situation, one said he refused to do the investigation, and another said that with my fair skin, I should get a skin specialist’s certificate so that I wasn’t sent that far away.

I did this, and the transfer was just changed from Mt. Isa to Toowoomba — on the Darling Downs. Bear in mind, I had just purchased a house and had not long come back from Townsville where I served in the C.I. Branch. Despite my requests not to, my partner ended up resigning from the job; she had been the dux of her squad and was training as a scenes of crime officer.

When the transfers first came out, my partner and I were talking with my sister and her husband about the situation. He said they were just mushrooming the situation. He explained that from where he sat, if they transferred one lesbian to Cairns and one to Coolangatta, the women wouldn’t change their sexuality but merely find another partner if their relationship broke down. If those two found a new partner in the police and then the hierarchy found out about the new relationships, and transferred those four women to say Townsville, Toowoomba, Rockhampton and Gympie, the same thing would occur. By this stage we were laughing about the Police Force being filled with lesbians.

I went to see the Deputy Commissioner shortly after that visit, and explained my brother in law’s scenario, having lesbians in every station. Stunned, his reply was, “Jill we didn’t think of that.”

The investigation was a witch hunt, and made the papers at that time.

Continuing my career in Toowoomba, I was put into the radio room. After 12 months of “being grounded” I spoke with the District Officer to find out how long my “penance” would last. He gave me some kind words about my work standards, and said to leave it with him. The following roster, I was put out into an operational role once more. I later ended up gaining a position in the Traffic Branch at Toowoomba.

After three years in Toowoomba, I approached the new Deputy Commissioner to ask how long I had to stay in Toowoomba. I put a strong case for jobs that had been advertised closer to my home in Brisbane. He said the hierarchy was happy with my performance in Toowoomba. I got a transfer to Beenleigh Station and all was reasonably well; I was back in my own home.

The interpersonal events at work sometimes caused me severe angst. For example, in 1990 I was promoted to Inspector and posted to the South Eastern Regional Office at the Gold Coast. While the two most senior officers in the Region were extremely supportive of me, some of my colleagues weren’t. I was a woman, the most junior in terms of years of service, a lesbian, the youngest in age, and the only commissioned officer with a tertiary education. Colleagues saw those five qualities as very negative.

A major personal quality often causing conflict was my innate honesty. I had been blessed with loving and supportive parents who practised social justice, who taught us to say what we mean and mean what we say, and I had three supportive siblings.

After about a year in the region, I applied for a transfer to the Queensland Police Academy. Subsequently in 1991, I went to the Academy. Then, in 1992, I went to the Community Policing Branch, promoted to Superintendent — the first woman in Queensland to achieve that rank. There was a major review of senior positions in policing with particular regard to responsibilities, budgets, etc. My position was upgraded to Chief Superintendent. After a very rigorous merit based process, I was promoted to Chief Superintendent — again the first woman in Queensland to achieve that rank. But there was more in store for me.

In 1993, I was called in to the Criminal Justice Commission (CJC) for an interview concerning an investigation they were doing at the time. The purpose was to reinterview me, among other things, about the 1977 lesbian investigation. It related to an issue that had been raised by the policewoman who was subject of their investigation.

Interestingly, at the time, a colleague saw me at the CJC and asked what was wrong. I explained what had happened. I explained to him that, among other things, I had just been interviewed about the 1977 lesbian investigation. I was angry and also explained that the CJC had the files, but that I had never even been offered a copy of the record of interview taken from me at the time (and nor did my partner). He went to see the chairman and for the first time, I saw, and was given a copy of the record of interview. It was not a true copy of the conversation that had taken place.

How many years of harassment was I expected to endure? Given my sister had been diagnosed with cancer, there were other issues happening within my family and support group, and I was over the harassment, it was time for me to look to where I might make a difference in some other field. I have never had any regrets about taking that stand.

What did and does that experience mean to me? It convinced me to speak out rather than to stay silent about the many issues that had, and would in the future, confront me. I challenged, with the Ombudsman, the discriminatory policies regarding the amount of effects single people were funded to take with them on transfer.

I spoke at a Gay and Lesbian Business Association’s meeting regarding members of the lesbian and gay communities being in policing, I spoke out about the disgraceful decisions made by members of the judiciary with regard to rape against women, and many others.

Instead of climbing into a hole, the whole process emboldened me and I became even more convinced of my guiding philosophy that, no matter what, I must be true to myself.

Others were not so fortunate with regard to their life’s experience. Some became more closeted, also, since the injustice in terms of equality with regard to aged pensions, not having a grandfather clause to give people some time to adjust, a number now deny their sexuality and their relationships. At times, staff will have no acknowledgement of the real person to whom they are providing nursing care and/or services.

Generalisations are generally wrong so one must be careful in assuming a person is from the lesbian community. For very justifiable reasons, including the fact that numerous folk that I know have never come out as a lesbian to their families, they won’t acknowledge their sexual preferences.

I could only promote the need to treat every person in your care or to whom you are providing service with respect, regardless of your own position, their situation, or your beliefs.

When my late partner was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer in 2008, we were open with regard to our relationship. The treatment regime was intense at this time, but the doctors, nurses, and others with whom we had to deal were generally terrific.

In fact, the nurse on the night shift when my partner was in palliative care, two nights before she died, said to me: “Jill, if it was my partner, I would want to hop into bed and have a cuddle. Come on we’ll tuck you in.”

That happened the last two nights of Lorna’s life; I appreciated their love and concern — for both of us. It was in St. Vincent’s Hospital Brisbane — a Catholic-based hospital.

We are not all the same; we are individuals with a variety of life experiences. We all deal with life differently. However, we all want service in a professional, humane and caring way.

For those who are open about their sexuality and for those who are not, families are sometime supportive, at other times they are openly hostile. Sometimes, a person’s sexuality is like the elephant in the room that is never spoken of and that may make it more difficult for them as they age.

With your help, the journey to be travelled may have fewer bumps in the road and may provide more care and support for us as we age.

(Photo credit: J.R. Latham, Val’s Cafe)

I am in awe of this woman. I am sorry she suffered as she did and her way of looking the world in the eye is brave and strong.

This story is really touching. It is horrible to think that discrimination was so prominent. As you said there are still bumps in the road that need to be faced but hopefully we are getting closer to equality.

@SpeakUAgainst

Why aren’t tyre gay /lesbian old age retirement homes

With regular facilities often located in non traditional gay areas and potentially none or little family support like straight elderly

This is a real issue that the community is ignoring