The marriage wars

Presidents, prime ministers, politicians of all sorts, candidates, bishops, gay activists and right-wing loonies of all sorts are talking about it. Same-sex marriage, once a back burner issue for the gay community, has reared its head as a frontline battle in places as diverse as Taiwan and the United States.

The Washington Post recently reported many conservative activists are planning to turn gay marriage into a major issue in next year’s US presidential elections. According to the Post, banning same-sex unions is a higher immediate priority for the Christian right than restricting abortion.

The issue has gained momentum in recent months with the Canadian decision to allow same-sex marriages, the US supreme court’s overthrow of Texas sodomy laws and a decision of the Massachusetts Supreme Court on gay marriage expected this month.

The prominence given to gay issues in the media and the very public battles in the Anglican church have further reinforced the conservatives’ siege mentality.

Matt Foreman, executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, recently told the New Jersey Star Ledger he believed that the buzz over the television show Queer Eye For The Straight Guy and Madonna’s open-mouthed kiss with Britney Spears at the MTV Video Music Awards had contributed to this rising sense of anxiety.

It was really an extraordinary confluence of events, that has made people say, -˜Enough already.’ Events beyond gay people’s control have made some people think we’re trying to cram our lives down people’s throats, Foreman said.

Richard Mohr, a philosopher who has written extensively about gay and lesbian rights and legal issues, draws a useful distinction between two views of marriage that he says are at the heart of the societal conflict over gay marriage. He writes of marriage as a way of experiencing the world versus marriage as a cultural ideal. The first involves the field of daily interactions; the other is rooted to people’s identities. In an essay for the Gay & Lesbian Review he writes:

Marriage viewed as a way of experiencing the world explains gays’ sudden interest in the issue, while marriage viewed as a cultural ideal explains the strength of the backlash against gay marriage. The unfortunate result is that in this battle of the cultural wars the combatants are not even fighting on the same field.

Mohr refers to an exchange between openly gay Democrat representative Barney Frank and Republican powerbroker Henry Hyde during a hearing about the 1996 Defence of Marriage Act (DOMA), which was the first attempt by conservative forces in America to enshrine a heterosexual definition of marriage in law.

In the exchange over DOMA, Frank kept coming back at Hyde trying to get him to specify exactly how same-sex marriage would threaten, change, or hurt in any way his own marriage or any other marriage. In the end Frank got Hyde to admit that two gay men or two lesbians getting married would not take anything away from Hyde’s own marriage, nor would any heterosexual lose any rights or benefits currently associated with their marriage. So exactly what was the problem? Hyde’s reply was stark and revelatory in its directness:

It demeans the institution. The institution of marriage is trivialised by same-sex marriage, Hyde replied. As Mohr comments:

The institution of marriage has now become completely detached from any actual marriage. It is only the concept or ideal of marriage -“ marriage wholly in the abstract -“ that concerns Hyde. Here we have left the realm of traditional social policy and entered the realm of cultural symbols.

Mohr’s distinction between marriage as everyday reality and marriage as institution is a useful one when trying to understand the battle over same-sex-couple superannuation rights, for example. For gays and lesbians this is a very simple matter about the everyday economic organisation of their lives -“ there are no logical public policy reasons to oppose it. The government’s opposition can only be read as ideological opposition based on particular notions of an institutional ideal.

Marriage as symbol recently played itself out in a fascinating way on the reality TV show The Amazing Race. This adventure series, a kind of cross between orienteering and a treasure hunt, followed 12 teams of two people competing across four continents, 24 cities, and 44,000 miles.

The couples ranged across best friends, work colleagues, a father and son, heterosexual couples and a gay couple. The show flipped between the 12 couples in snappy fast cuts and every time a couple came on screen again,

their name and designation would flash up: Monica and Sheree: NFL wives/soccer mums or Russell and Cindy: friends, dating or Debra and Steve: married/parents.

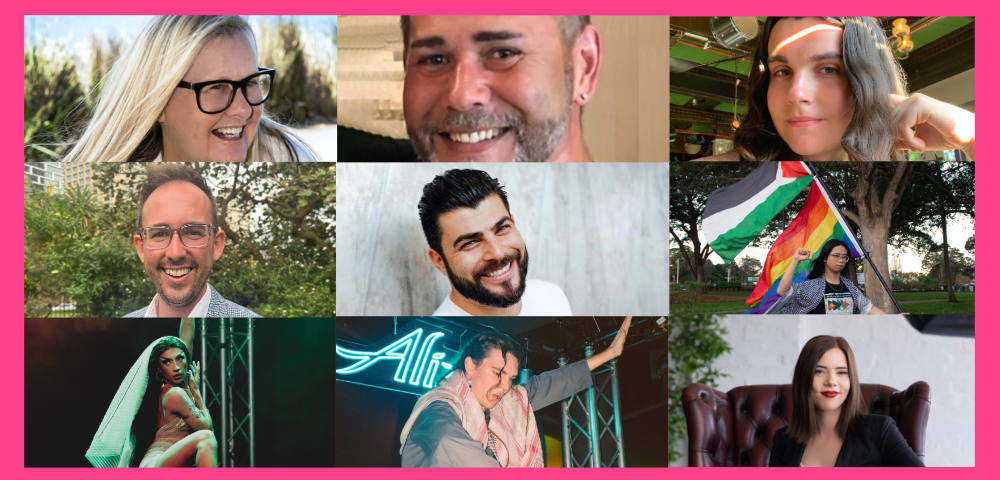

In previous episodes when gay couples had participated, they had been designated life partners. In the most recent series, the couple who eventually went on to win the series, Reichen and Chip (pictured), insisted that they be labelled as Married. They had celebrated their union in a ceremony with 200 of their friends and family and felt they were as married as any other couple. They actually celebrated their one-year anniversary during the show. CBS after some discussion agreed to the married label and were very forthright in defending the decision when the inevitable backlash came from the religious right.

Mike Haley, the manager of the Gender Issues Department at Focus On The Family, had this to say about Reichen and Chip in an article posted on the organisation’s website:

The Amazing Race was indeed amazing this season -¦ It was amazing because the two gay contestants crowned the show’s champions -“ Reichen and Chip -“ proudly declared to America that they are married -¦ The difference, of course, is that they aren’t really married. At least not in any sense that any US court or state recognises -¦ No one is more aware of this than gay activists. That’s why they couldn’t be happier that CBS let Reichen and Chip call their relationship whatever they wanted -“ and that the duo was the last team standing. Those activists know that the more Americans hear something, even when what they’re hearing is a lie, the more likely they are to believe it.

Haley is spot-on in his assessment of the power of repetition. Because this is actually a debate with very few substantive issues, both sides are essentially reduced to the repetition of symbolic mantras.

But Reichen and Chip were not the only symbols on The Amazing Race. One of the other couples had an even more striking tag line: Millie and Chuck from Chattanooga, Tennessee, labelled themselves: Dating Twelve Years/Virgins. Like the world’s most famous former virgin, as Britney Spears was recently described, Millie and Chuck were setting themselves up as a poster couple for the sanctity of marriage, and were forthright about being bible-believing Christians.

It’s interesting to note that when the couples got together at one point, both Reichen and Chip and Millie and Chuck had to negotiate a coming out process. By and large, gay marrieds Reichen and Chip gained much more ready acceptance than the virginal Millie and Chuck.

As one of the other contestants exclaimed: Screw the gay marriage. I can’t believe I’m sitting next to a 28-year-old virgin.

Reichen and Chip described their stance and CBS’s support as revolutionary. In a post-victory interview with the gay magazine The Advocate, Reichen had this to say about their being tagged as a married couple:

It’s revolutionary. You know, it’s kind of saying, -˜Yeah, you know what? If the state isn’t going to recognise the rights that people want to have, then the people will go ahead and recognise that for the state.’

It’s a shame the revolution didn’t last. Reichen and Chip recently announced that they have split up. Reichen and Chip put a positive spin on it: they now want to be seen as role models of the perfect, amicable, caring break-up.

With same-sex marriage now firmly on the agenda, gay and lesbian divorce is bound to be the next big growth industry.